Whilst discussing the design of a network session that would explore what it takes to establish a successful strategic alliance we kept coming back to the question ‘why’? The more we read, and debated, the more we were reminded of the dangers of putting the ‘cart before the horse’: investing resources (time and money) in a relationship before we are really clear on its purpose. So this, for us, was an important starting point, and forms the focus of this blog.

Strategic alliances are becoming increasingly important

Why even talk about strategic alliances at all? Well, the fact is they are important, and becoming increasingly so.

“one third of the revenues of the top 2,000 US and European companies is as a result of alliances” [1]

At a macro level, there are various forces driving the increase in alliances, including the blurring of competitive boundaries, advances in communication, intensified competition, and the fact that the technology we use necessitates cooperation with others (i.e. for those problems that can no longer be solved with a hammer, we need access to appropriate levels of expertise)

Beyond this, we are seeing a worldwide restructuring of the way we do business. In the UK alone, more people are deciding to set up their own businesses. Last year, 15% of the total workforce, some 4.6 million workers, were self-employed, the highest since records began in the early 70’s [2]

“Today businesses grow through alliances, all kinds of dangerous liaisons and joint ventures, which, by the way, very few people understand.” Peter F. Drucker, Management [3]

And that’s the thing. When ‘60-70% of all alliances fail’ [4] understanding alliances and how to make more successful alliances, is central to the growth and performance of organisations across the globe. But, where do we start?

What do we really mean by a strategic alliance?

There are many labels for alliances, as illustrated by the ‘alliance spectrum’ depicted here.

To us however, what is more important is to move beyond the surface level labels to first understand what we really mean by a ‘strategic alliance’.

To explore this, we invited our network of business owners to individually draw a picture that represents what a strategic alliance means to them. The creations that were presented back were highly imaginative! We had an international space station, two people with interlocking brains, a set of coloured coded people each contributing a piece to complete a puzzle, a collective force for competition, a mental decision process, and organisational development akin to a traveller’s journey. How would we sum all this up, in simple terms?

Strategic alliances, for our network of business owners, focused on taking their organisation from where it is currently (the reality) to where they want to see it in the future (the longer term goal). It was about coming together with others, identifying complementarity and achieving something better, through cooperation, than you could otherwise achieve on your own. Complementarity meant more than capabilities, and included shared visions and values, and opportunities to innovate. Outputs were important, with the financial imperative evident, and the need for shared risk and return. The choice of partner was crucial, and the desire to turn over the numerous rocks on the road to finding the ‘right’ partner was central to success.

What can a textbook definition add to this? A strategic alliance is:

“a tailored business relationship based on mutual trust, openness, shared risk, and shared rewards that results in business performance greater than would be achieved by the two firms working together in the absence of partnership” [5]

This definition reinforces our business owners’ perspective that an alliance is about working with another party to achieve a level of performance that would otherwise not be possible. It also draws attention to a central facet of alliances – relationships. We’ll be talking more about the dynamic of this relational aspect in a later blog.

Defining a purpose for your strategic alliance: the thirst for knowledge

For smaller businesses, strategic alliances are vital in helping them achieve faster, more economical growth, and responding quickly to consumer tastes and fashions.

Strategic alliances can provide an organisation with a range of tangible resources, some of which may include: cash, machinery and equipment, people power, technology, and so on. Our business owners also raised a number of other motives for entering into alliances. They were keen to build on the strong relationships they already have with their value chain. In doing so, they saw potential learning opportunities, access to new markets, innovation potential in products or services, and improved operational efficiencies.

This alludes to the importance of intangible assets, such as knowledge [6]. Knowledge forms the foundations of competitive advantage, as it is something that cannot be easily copied by competitors [7]. Is the purpose therefore, of a strategic alliance the acquisition of knowledge from alliances partners? We would suggest not. Treating alliances in this way might well lead to a competition for learning, whereby alliance partners seek to learn at a faster rate to achieve a positive balance of trade in knowledge. This can destabilise relationships even if relationships and trust are well established.

So if alliances aren’t about grabbing knowledge from others, what are they about? In reading around the topic the following distinctions emerged [8]:

- ‘exploration’ or ‘knowledge generation’ – alliances as vehicles of learning

- ‘exploitation’ or ‘knowledge application’ – alliances as exploiters of complementarities

These approaches focus on alliance partners retaining their core competences and specialised knowledge and collaborating with others to access additional capabilities. Which begs the question: which elements of knowledge are underutilised in your organisation?

So, before investing significant time and money in relationships, stop to think about what is drawing you towards a particular partner. Look to define a purpose for the relationship from your perspective, as well as understand it from a potential partner. Remember that it is about knowledge and complementarity, achieving something you couldn’t otherwise achieve on your own, and building relationships that take you, and your organisation, to where you want and need to go.

MAD challenge

In reading this section, we would ask that you reflect on the following questions:

- what are your drivers for forming an alliance?

- what are your partner’s drivers for forming an alliance?

- what dimensions (i.e. criteria) will you use to assess whether a strategic alliance is appropriate?

- What do you want to achieve from an alliance?

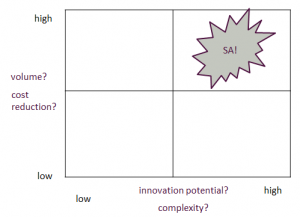

We know the world is more complex that a 2×2 matrix, however a good way to start is to identify a couple of key product/service drivers. These are drivers that will urge you to explore the potential that an alliance could offer. For instance, you may focus on making a small number of high value complex products, and when you notice the potential for a large volume of simple products, as part of your portfolio, you have a decision to make as to how best to exploit this. Beyond this simple approach, you’ll need to challenge yourselves to think of this with greater complexity and in multiple dimensions.

For further information on the BIG Network or any of the Business, Improvement and Growth (BIG) programmes for ambitious owner-managers, and their teams, please get in touch with Simon on 01227 824740 or S.O.Raby@kent.ac.uk

Selected References

[1] Booz-Allen & Hamilton. 2000. The Alliance Enterprise: Breakout Strategy for the New Millennium.

[2] Office of National Statistics, 2014, Why has the number of self-employed increased? Accessed 27th May 2015.

[3] Drucker, P.F. 2006. Classic Drucker, Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

[4] Hughes, J. and Weiss, J. 2007. Simple Rules for Making Alliances Work, Harvard Business Review, p122-131

[5] Lambert, D.M., Emmehainz, M.A and Gardner, T. 1996. Developing and Implementing Supply Chain Partnerships, International Journal of Logistics Management, 7(2): 1-17.

[6] Das, T.K. and Teng, Bing-Sheng. 2000. A resource-based theory of strategic alliances, Journal of Management, 26(1): 31-61

[7] Barney, J. B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120.

[8] Grant, R.M. and Baden-Fuller, C. 2004. A Knowledge Accessing Theory of Strategic Alliances, Journal of Management Studies, 41(1): 62-84.