Gateways’ Director Professor Mark Connelly discusses the place of the puttee in Great War imagery.

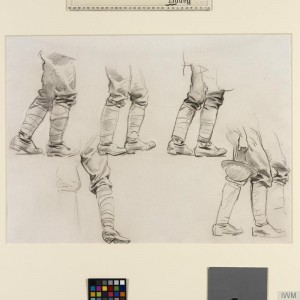

There is a piece of kit used by all British and French soldiers that defines the Great War in my mind, capturing it in time and space. It delineates it from the second total conflict of the twentieth century, but links it back to the armies of the late nineteenth century and conjures up images of dusty imperial outposts on the North-West Frontier. I am, of course, referring to the humble puttee. I can’t quite identify when I became so fixated on this item, but it was certainly in my youth as I was first becoming interested in the Great War. I think it may have been to do with my local war memorial – a good, solid piece of bronze sculpture by Newberry Trent – of a sentinel soldier presenting arms guarding, as well as representing, the civic pride and honour of my East London suburb. Looking up at him on his plinth, it was impossible to escape the fact that his mounting at just above eye level meant that as the head craned up to take in his full size, the first detail caught by the eyes was his boots and puttees. Just what were these strange things? Not yet aware of the wonderful piece of technical Anglo-Indian Hobson-Jobson, I labelled them ‘bindings’. The real term was finally disclosed to me on my first trip to the Western Front when I was asked about the things that interested me in the Great War. I mentioned that there was something mesmeric about those bindings. ‘Aah, you mean the puttees,’ said an old chap from Blackpool with a fabulous Lancashire twang. So, that left me with a linguistic issue. Were they ‘puuuutteees’, as the Lancashire accent inferred, or ‘puttees’ as in window putty? To be honest, I think that one is an open question and either is acceptable.

So, what was it about the puttee that caught my imagination? I think first and foremost it was the idea of having what looked like a very tight serge wrapping bound tightly around the lower leg and how this might feel when wet. Secondly, and very much linked to this first point, I couldn’t shake the association with those wonderful photographs of chaps burdened down with huge Lee-Metford rifles wandering along a scrubby track in South Africa, or standing around on a rocky valley bottom watching mountain artillery batteries firing on some invisible Pathan position. The common things linking both sets of photographic images stored away in the mental picture album were sunshine, blue skies and dust. In my mind, it never rained in South Africa or on the North-West Frontier. Cold, at times bitterly cold, maybe, but rain never. In short, I couldn’t conceive how these blessed things could ever prove a blessing to a soldier attempting to do his job in a much wetter climate. Throw in miles of trenches and the wonder became even greater. But, and here is where I grew confused, the French army took to wearing them, too, so they must have had what we now call a good USP for them to have been consciously adopted specifically for this particular theatre. Unable to figure out just how they could be any good at all, I remained fixated by them.

As we all know, the Great War generated a huge number of photographs, and as we also all know, for the Anglophone world at least, the Great War is dominated by images of trenches, and they are mostly associated with the Western Front. Another dominant image, visual and literary, is of the misery of men standing about in wet holes in the ground. Yet another thing we all know about the Great War is that the sun shone on two days only – 4 August 1914 when supposedly a million men went rushing off to the recruitment offices bathed in a Bank Holiday glow and 1 July 1916 when an entire generation was, so the common legend would have it, annihilated under a blazing sun. The rest of the time it poured down unremittingly. ‘Never a dry day in the trenches,’ as a character in Alan Bennett’s wonderfully insightful Forty Years On has it. In turn, this naturally concentrates the mind on the lower limbs and particularly from the knee down to the toes. We imagine men saturated. We imagine the awful misery of constantly being soaked to the skin and the creeping horror of trench foot. We see men stamping about in a thick Flanders porridge because that’s what all the films show us at some point. And, in those original sepia images nothing seems more sepia-khaki than the puttee itself. The puttee is the awful sponge of the soaking rain, the thing to which the mud clung naturally because they were so alike in colour. The puttee is the colour of Great War memory – sepia. One other colour does occur in a mental Dulux paint list of the Great War – a violently vibrant splash of poppy red. But even here it is wet, blood wet, splashy. As Wyndham Lewis wrote of the Third Battle of Ypres: ‘The very name [Passchendaele], with its suggestion of splashiness and of passion at once, was very appropriate… The moment I saw the name on the trench-map, intuitively I knew what was going to happen.’ Soaking wetness is the essence of the Great War and the puttee tucked into the boots is its encapsulation. And, thanks to the presence of so many soldiers on war memorials sat up high on plinths, it is the initial moment of remembrance and memory. Most of those soldiers have pristine puttees as they are statues of sentinels, as in my home, but a few have dragged that Flanders mud back with them most notably Philip Lindsey Clark’s wonderful memorial for Southwark in Borough High Street. His soldier purposefully strives through the slough of despond. He is therefore not the pitiable soldier stood against the parapet of a flooded trench keeping endless sentry hours in unspeakable conditions. This one is the master of the battlefield, but the sheer fact that he is dragging himself through such muck focuses attention on the mud, the boots and the puttees.

All of these thoughts came crashing back to me when the BBC World War One at Home project ran a story about the textile manufacturing firm of Foxes and their wartime production of puttees. I was amazed to see that the factory is still going and they can still make them. Or perhaps a more fitting way of putting it given their dominant association is to say ‘pump them out’? By this time, however, I had learnt from various army manuals, memoirs and living history enthusiasts that the puttee can be a remarkably effective shield against cold, muck, dust and wet provided it is correctly bound. I must admit that that proviso has allowed me to maintain more than a scintilla of doubt about its actual effectiveness. And this explains why, whenever I see any image of British and imperial soldiers in the Great War, I always find myself viewing from the feet upwards.