On Tuesday 11 November 2014, Gateways held a study day on First World War theatre at The Marlowe, Canterbury. The day included workshops on primary sources, talks from leading researchers, discussion of key historical themes, and rehearsed readings of little-known wartime plays, as well as the launch of Gateways’ new travelling exhibition on theatre and performance in the First World War. Organiser Dr Helen Brooks reflects on a successful event:

“It is easy to get bogged down (excuse the pun) in the Battles of Trench Warfare, but now I see that plays of the time are an insight into the culture of the time, which to me is equally as important in understanding the reasoning behind the Great War. This new insight has opened up a whole new perspective”. Lindsay Kennett, who wrote these words in an email to me last week, was just one of the 30 plus participants who took part in our public study day on First World War theatre, on Tuesday, 11 November at the Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury. The aim of the day was to raise public awareness about how looking at theatre can shed new light on ideas about, and responses to the war: for Lindsay and the many other participants who echoed her sentiments in their feedback, it was clearly a great success.

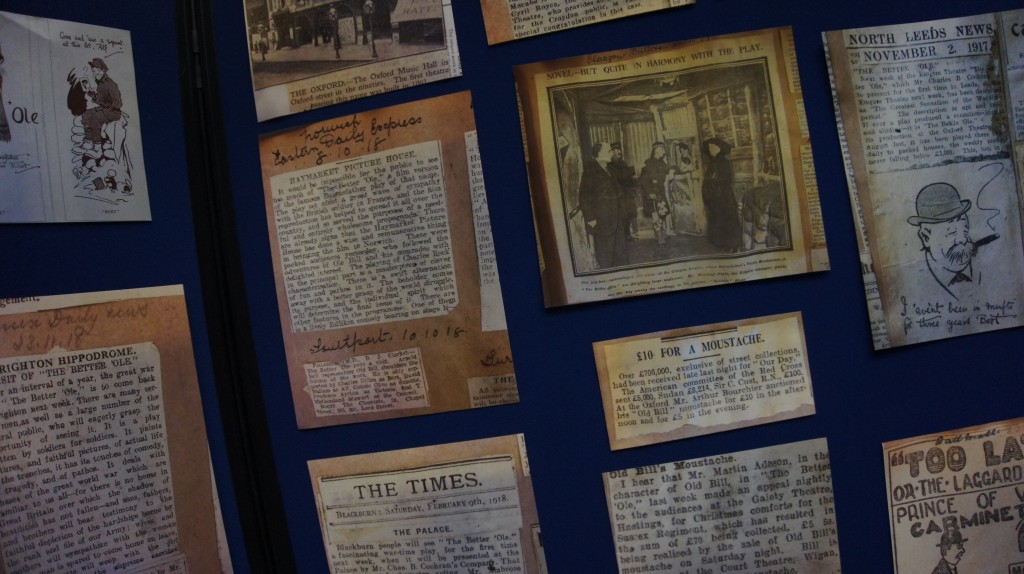

Over the course of the day we got stuck into a diverse range of activities, all of which were facilitated ably by a team of fantastic student, and ex-student helpers from the Drama Department in the University of Kent’s School of Arts – Rebecca O’Brien, Rebecca Sharp, Kinga Krol, and Charlotte Merrikin. Beginning with a brilliant workshop run by Jane Gallagher, the Special Collections archivist at the Templeman Library, participants had a chance to get ‘hands on’ with sources from Special Collection’s archives (including newspaper clippings, scripts, programs and playbills) and to interrogate them in order to answer questions such as ‘how did the theatre “do its bit” for the war effort?’, ‘what impact did the war have on the theatre industry?’, ‘in what different ways was the theme of war treated in performance?’, and ‘how did audiences change during the war?’. This last question then led us into Professor Viv Gardner’s (University of Manchester) stimulating talk about audiences during the war. Reminding us that audiences were made up of diverse groups and that their responses changed depending on the context of the performance, Viv also drew on some moving stories about individual spectators which brought to life the experience of theatre-going during the war.

After a delicious lunch, courtesy of the Marlowe, and an opportunity to chat to each other about our diverse interests and backgrounds (participants included students from the Langtons schools, members of the Western Front Association, and local historians, to name but a few) the afternoon began with rehearsed readings of three First World War one-act plays: The Devil’s Business by J. Fenner Brockway (1914); God’s Outcasts by J. Hartley Manners (1919); and A Well Remembered Voice by J.M. Barrie (1918). It was quite something to see these plays brought to life, the first two quite probably for the first time ever. The actors, including three University of Kent Drama students, Zach Wilson (PhD), Alexander Sullivan, and Louise Hoare, all did an excellent job, especially as the plays were quite distinct in tone and style, and as the actors had only had two and a half days rehearsal in total. After a stimulating discussion about the plays, with some excellent insights from audience members, the day was then rounded off nicely with a thoughtful talk by Dr Andrew Maunder (Reader at University of Hertfordshire) about his own experience of staging ‘lost’ WW1 plays, and in particular A Well Remembered Voice.

This wasn’t the end though! After just a few hours break – during which it was exciting to see our pop-up exhibition on WW1 theatre in the Foyer attracting a lot of attention from audiences waiting to see the RSC – many of us were back at the Marlowe for the evening rehearsed readings. It was great to see an almost entirely new audience for this. As well as a number of Kent students people came from as far as Dover to join us for this exciting performance. Three of the one-act plays we shared were the same as in the afternoon (although the performances were quite different in energy, something the actors reflected on in the questions afterwards) and we also added an unpublished short play about the Belgian experience during the war entitled There was a King in Flanders (1915) by John G. Brandon. With these four pieces we therefore covered not only the chronological breadth of the war but also a number of different responses to this world event. From The Devil’s Business (1914), a biting satire on the arms trade and its place in fuelling conflict, which was banned in London during the war; to There was a King in Flanders (1915) with its focus on a dying Belgian soldier; and finally to God’s Outcasts (1919) and A Well Remembered Voice (1918) both of which offer sharply different responses towards grief, the plays as a whole offered new insights into the diverse ways in which theatre treated the war between 1914 and 1918. And with insightful comments and an enthusiastic response from the audience, it seems there’s certainly potential to hold similar events in the future.

If you’d like to find out more about Theatre of the First World War, contact Dr Helen Brooks at h.e.m.brooks@kent.ac.uk. Our pop-up exhibition on Theatre of the First World War is available for free loan to theatres, schools and other public institutions. If you would like to host this exhibition simply get in touch with gateways@kent.ac.uk. There is no charge for hosting or delivery.

This study day was one of a series of events being run by Gateways to the First World War. To find out more visit our events page.

All photographs courtesy of Leila Sangtabi, University of Kent.