Gateways’ Dr Emma Hanna discusses Easter in the trenches in her latest blogpost.

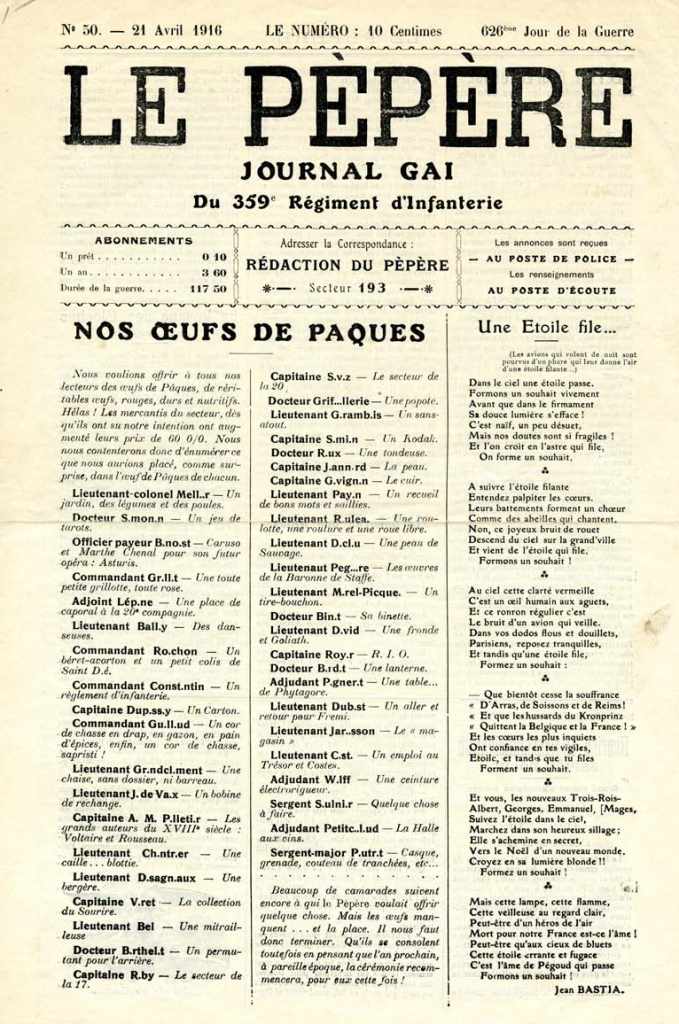

As we approach Easter I’m sure I’m not the only person wondering how the festival was celebrated by the troops during the First World War. A fascinating glimpse into French army life can be provided by one of their many trench newspapers – Le Pépère — Journal Gai du 359ème Régiment d’Infanterie (Merry Newspaper of the 359th Infantry Regiment). The first issue dates from April 21, 1916, two days before Easter. The front-page feature is “Les Oeufs de Pàques” (Easter Eggs) which lists the regiment’s officers next to what each should ideally receive in his oeuf, drawing on a French Easter tradition of exchanging confectionary eggs containing surprise gifts. As with some of the British trench newspapers, such as the Wipers Times, missing letters have been replaced with punctuation marks, perhaps due to a shortage of letters in the print.

The Imperial War Museum has a photograph of German troops celebrating Easter in their dugout in the Champagne, 8 April 1917. The phrase “Happy Easter – Frohliche Ostern” can be seen written on the door.

For Russian troops the Easter festival was of greater importance than Christmas. Therefore this is a particularly fitting time to dig out the testimony of someone who witnessed an Easter truce on the Eastern Front in 1916. Friedrich Kohn was serving as a medical officer with a Hungarian regiment in Galicia, where Russian and Austro-Hungarian forces were facing each other in entrenched conditions entirely similar to those on the Western Front. In 1981, in a letter to Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton as they were working on material for their book and television programme Peace in No Man’s Land, Kohn recalled the events of Easter Day 1916:

The winter of 1915-16 was very severe and when I joined my regiment at the end of February the country was covered deep in snow. No military action was possible […] The thaw set in and the peace stopped artillery duels between the Austrian and Russian armies started, sometimes by day, but more frequently during darkness.

Then suddenly on Easter Sunday, about 5 o’clock in the morning, about twenty Russians came out of their trenches, waving white flags, carrying no weapons, but baskets and bottles. One of them came quite near and one of our soldiers went out to meet him and asked what he wanted. He asked whether we would not agree to stop the war for a day or two and, in view of Easter, meet between the lines and have a meal together. We told him that first we would have to ask the military authorities whether such a meeting would be possible. The Divisional Commander refused permission. Nevertheless at 12 noon the Russians came out of their trenches and brought with them their military band, who came playing at full strength, and they brought baskets of food and bottle of wine and vodka, and we came out too and had a meal with them. We also had food and wine to offer.

During the meeting both sides seemed to be embarrassed, but both sides were polite to each other and consumed the food and drinks we offered to each other. After a few hours we all went quietly back to our trenches.

I talked with a Colonel who spoke perfect German and he told me that he had lived for several years in Vienna. When I asked him why he was always firing shrapnel at my first aid post- he told me he knew exactly where it was – he promised to leave me alone and he would send a rocket if he had to leave. For the next fourteen days I was left unmolested. Then he sent me a rocket, telling me that his unit were leaving.

Kohn survived the ensuing Brusilov offensive of May that year. He survived the First World War as he later survived imprisonment by the Nazis before the Second World War. His letter to Brown and Seaton concluded that

I have seen demonstrated in front of my own eyes that suddenly people who are trying to kill each other, and will try to kill again when the day is over, are still able to sit together and talk to each other.

Friedrich Kohn’s words taken from Malcolm Brown & Shirley Seaton, Peace in No Man’s Land (Pan, 1984)