Dr Will Butler, University of Kent

The outbreak of the First World War only had a very limited impact on the town of Folkestone during its opening weeks. Despite the fact that many of its summer visitors had left in a flurry of panic in its opening days, many did not, and the town had also begun to fill with British soldiers ready to embark for the front. However, by the middle of August allied forces had suffered a series of setbacks and its armies were on the retreat along with many thousands of refugees. Many fled westwards, but others attempted to reach the ports of Calais, Boulogne, and Antwerp in an attempt to cross the channel.

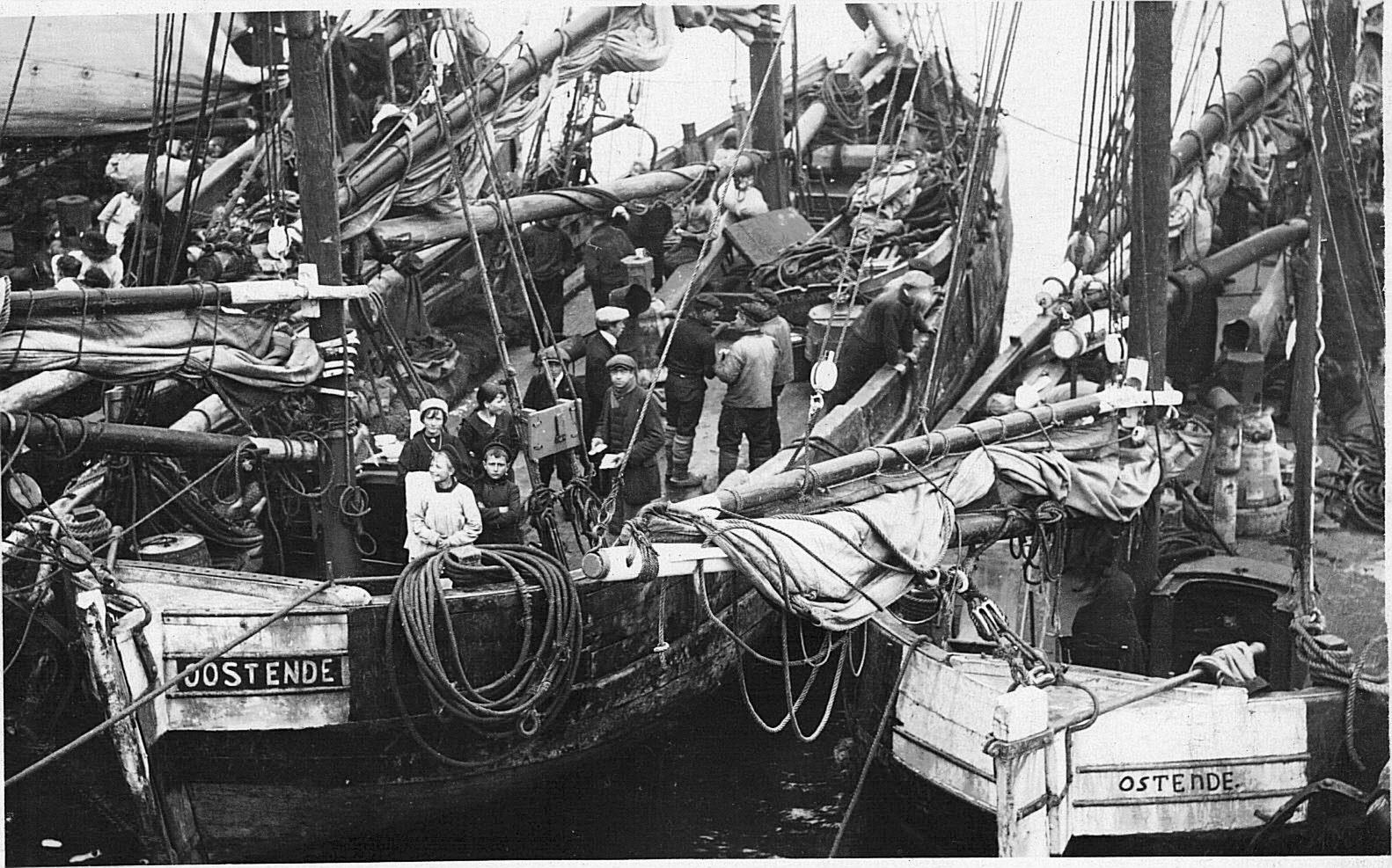

Initially, penny packets of Belgian soldiers began to arrive at Folkestone. The first boat from Calais brought 72 men from 12 different regiments. These men had fought at Namur and Liege, and the fact that they had come from so many different regiments shows just how much the Belgian army were in disarray. Within a few days, a conveyor belt of civilians began to arrive from the Continent, many of them in commandeered fishing boats. An extract from an article written by the Folkestone correspondent of The Times perhaps best illustrates the scene:

‘Gradually at first and very rapidly during the last week or ten days there has been a great change. The town is full, hotels and boarding-houses are crowded, and there is a constant stream of people walking along the Leas. A huge crowd gathers daily outside the closed gates of the Harbour Station and stands there for hours to watch the thousands of people landed every afternoon who pass out to take up their temporary abode here. But it is not the usual holiday crowd which Folkestone knows so well. These sad-faced people, who walk soberly about or gather in little groups and discuss solemnly topics which are evidently of intense interest to them, are not happy rollicking, holiday-makers, nor is their language ours. There is far more French than English heard on the Leas in these days, for Folkestone is becoming a town of refugees’.

It was estimated that by 5 September, as many as 18,000 refugees had arrived in Britain through Folkestone Harbour and there was no sign that the numbers would fall. A Folkestone War Refugees Committee was quickly formed in the town and a Belgian Relief Fund was instigated by various newspapers around the country. Each refugee was given a medical examination by a doctor before they left the Harbour, some were then sent on to London, and others were found jobs locally, such as hop-picking. Above all, free meals were provided to all who required feeding: as many as 6,000 meals each day.

All classes of people had made the journey across the Channel. Many ‘smartly-dressed’ people of the middle classes stayed in the larger hotels and boarding houses surrounding the Leas. The poorer visitors, described as ‘terribly poor’, with little or no luggage were put up around the town in rooms volunteered by many of the townspeople. The Refugee Committee was praised very highly for its endeavours. Described as displaying ‘untiring zeal, cheering drooping spirits, feeding the hungry, helping the helpless, and directing and advising all who stand in need’.

The stream of refugees continued almost every day until the middle of October. By this time the town was as full as it would be at the height of the tourist season and few unoccupied rooms could be found anywhere in the town. Over 100,000 Belgians had passed through Folkestone in only a few months and as many as 15,000 had taken up residence. As a result, more funds were required to ensure that they could be cared for over the winter months. Many of the shops had put up signs in their shops advertising in French and a specific paper was printed, Le Franco-Belge, which could keep those who wish to be informed of news from the front. All effort was made to make the refugees feel welcome and comfortable. For many it would be at least another four years until they could return home.

The citizens of Folkestone clearly embraced the presence of the new residents. In July 1915, the town celebrated ‘Belgian Day’, to coincide with the Belgian national holiday. The Town Hall and other businesses flew the black, yellow, and red flag, and many Belgian children were seen selling them in the streets. A ceremony was held at the Roman Catholic Church and the Mayor of Folkestone spoke of England’s admiration for ‘gallant Belgium’.

Other events regularly took place throughout the war, and the town was visited by many dignitaries as a result of its hospitality to the Belgian people, including the King and Queen of the Belgians who were warmly received. Famously, Signor Franzoni painted a portrait which depicted the arrival of the first Belgian refugees at the Harbour, which can still be viewed in the town. A tablet was erected outside the Town Hall in testimony of the work carried out by the townspeople. Finally, a message was received by King Albert at the end of the war, when a Mausoleum was erected at nearby Shorncliffe Military Ceremony, who stated that ‘Folkestone had earned the admiration not only of the Belgians, but also of the whole world: yes, the whole civilised world knew how the town of Folkestone had received them with such cordiality which would never be forgotten’.