A trans friend once asked me when I first knew I was cis.[1] (Some of their best friends are cis!). I’m not sure. Perhaps it was watching the 1995 Andrew Davies adaptation of Pride and Prejudice on the BBC. I knew that I liked Lizzie Bennet, and wanted to spend time with her, but I wanted to be Mr Darcy. Besides the fact that my good opinion, once lost, is lost for ever, I bear very little resemblance to Mr Darcy. I thought I had a chance of being Mr Bennet when I hit middle age. I developed a terrible fear that I might end up most closely resembling the tedious bore Mr Collins.

I knew that there was this thing, manliness, that I wanted to have. It seemed to involve caring for the people around one, treating people with respect, cultivating one’s manners and understanding, and developing control over one’s emotions. Possibly, horses, fencing, or open air swimming were involved.

It struck me, on reflection, that there were lots of ways of being masculine. Cary Grant, David Attenborough, Sidney Poitier, Noel Coward, Brian Blessed, Sean Bean, Tom Baker, Hugh Grant and my father were all quite obviously masculine. But it’s difficult to put one’s finger one what all of these people might have in common. If the aim were to define manliness in terms of a set of features all and only men have, it would be less than straightforward. Descriptively, I am obviously masculine. I’m 6ft 5in, with a bushy beard and a big deep booming voice. People are very seldom confused about what pronouns to use when referring to me. But merely that I look like I stand up to wee doesn’t tell you all that much about my gender.

My beard gets shorn periodically when I want to eat soup unstrained, but my gender is important to me in a way that the presence or absence of facial hair is merely incidental.

In about 1997, I was visiting family in Scotland. My mother enters the room and says ‘Graeme, you’re a strapping young lad! Can you go and push the postman’s van out of the snow?’. I was not a strapping young lad. I was a rather slender 13 year-old. Feats of physical prowess were not something you would have associated with me. But out to push the postie’s van I went. That I went should not be a surprise; I was sent. But I remember reflecting on a really odd thing. Prefacing the request with ‘you’re a strapping young lad’ flattered me. I felt motivated to act the part of the strapping young lad. I wanted to be viewed as masculine.

This thought – that I was motivated by manliness – seems important. It seems to be part of who I am, in a way that makes me feel like the best version of myself. My beard gets shorn periodically when I want to eat soup unstrained, but my gender is important to me in a way that the presence or absence of facial hair is merely incidental. In the project of cultivating myself to be a person I like more, I can’t imagine cultivating my gender away. And my gender is tied up in lots of ways with a particular culture and a particular moment in time. It is not some ahistorical cosmopolitan sort of manliness I have, but one rooted in Scottishness, Englishness, and comprehensively educated aspirational middle-classness.

The Tension in Manliness

In the same way that I am proud of my nationality – I don’t think it superior to others, but feel a sense of belonging and attachment to it – I am proud of my gender. But as with my nationality, my gender carries baggage that it is hard to be proud of. The history of Britain is a morally mixed record at best. The sins of Empire leave a heavy reckoning. Similarly, the stifling of talent and opportunity of women, the physical intimidation, and the violence towards them represent a problem that men, if they are to be proud of being men, have to reckon with. And there are ways masculinity seems to create bad character traits; the tendency to turn everything into a competition, and to avoid ever admitting weakness. (I once tried to ‘walk off’ a collapsed lung. It didn’t work.)

I entirely understand why seeing a tall dark figure at night might lead someone to clutch their handbag, or put their keys between their fingers in preparation to defending themselves. But, of course, I’m not intending any of these things. I’m just having a conversation, or walking home.

I am naturally an enthusiastic conversationalist; sometimes this means that I dominate a conversation. I’m tall and I gesticulate when excited. This means that I can take up a lot of space (not to mention the effects of my big deep booming voice). I have an unfortunate tendency to loom. When I walk home at night, I can see women react fearfully to the tall stranger on the other side of the road. I can understand that many women are exhausted by having someone else dominate conversations, and simply take up too much space. I entirely understand why seeing a tall dark figure at night might lead someone to clutch their handbag, or put their keys between their fingers in preparation to defending themselves. But, of course, I’m not intending any of these things. I’m just having a conversation, or walking home.

There’s a tension between feeling proud of my masculinity and being aware of the ways in which men in general, and me in particular, impact on the people around me. It’s easy to get the impression that it is men who are the problem. Masculinity is often described as ‘toxic’ (though usually what’s meant is that there are some ways of being masculine that are toxic). Some feminist philosophers define masculinity in terms of the oppression of women. What it is to be a man, on such accounts, is to be a member of the group who benefit from the oppression of people who are perceived or imagined to have certain reproductive organs. How can one be proud of being a beneficiary of oppression?

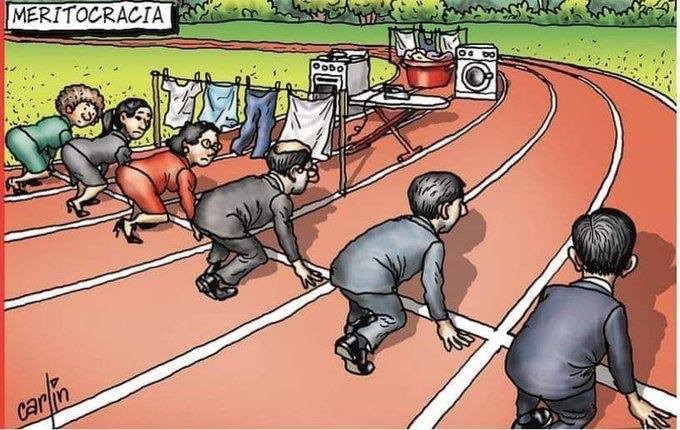

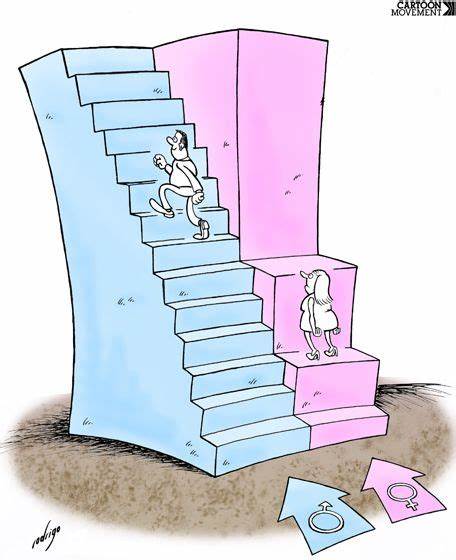

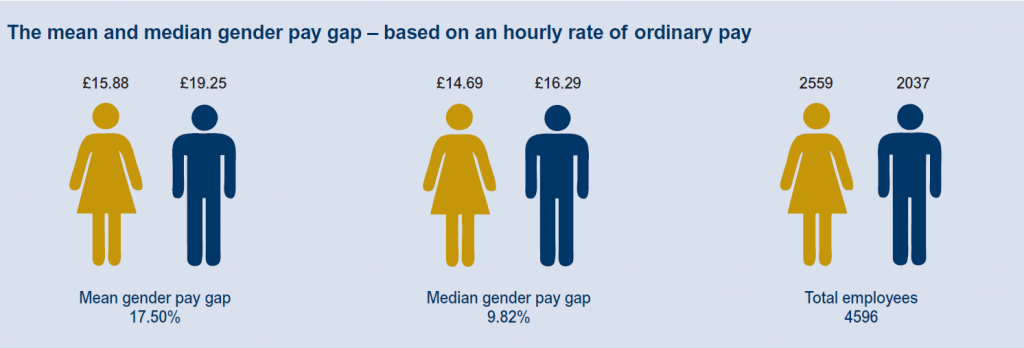

One solution is to dismiss the concerns of feminism. But this is a poor solution. Even if one isn’t allied to the political movement or persuaded by the academic literature, most of us have enough women friends to find out, if we listen, that there are many ways in which women have things pretty hard. The masculine tendency to turn everything into a competition is frankly unhelpful here. There are problems women have that men simply don’t have, and ones where women systematically come off worse than men.

In fact, there’s a double-bind here. Men, if they feel this tension between liking their masculinity and acknowledging the ways in which women are harmed by men dominating public discourse, have to deal with a difficult thing. But, insofar as they recognise that men take up too much space (and insofar as they think manliness has to do with caring for one’s friends), asking for help resolving this tension is very difficult to do, and so is usually attempted alone. Add to that the unfortunate prohibition on admitting weakness.

After all, manliness involves caring for the people around one; we learnt that from Mr Darcy.

This double-bind has real consequences. According to UK Government Data, suicide was the leading cause of death for both men aged between 20 and 34 years in the UK, with men three times more likely to commit suicide than women. It’s not likely that the double-bind I have described is responsible for most of these deaths, but making it harder for men to feel like they can resolve the tension I describe risks adding to these statistics.

For me this hits close to home. In 1996, my father had a nervous breakdown. After that he suffered from clinical depression for 20 years, and never went back to work. I can remember my dad telling me about nights where he lay awake needing the toilet, but couldn’t get out of bed in case he killed himself. I used to ask him why he had let things get that bad that it had made him ill. He didn’t have a choice, he said. He couldn’t get out of the situation because he had a wife and kids to provide for. In this one case, at least, it was caring about other people that led to the breakdown. After all, manliness involves caring for the people around one; we learnt that from Mr Darcy.

It’s not simply a question of asking men to emote more. Men already emote plenty; singer-songwriters frequently record stories of men’s pain, misery, heartbreak, and loss. And not all spaces are safe ones in which to make oneself vulnerable. If everything is a competition, healthy, nurturing friendships are hard to make. Men taking up even more space complaining about their fears, and making yet more conversations about them doesn’t sound like progress. Double-binds are usually tricky to resolve.

This is, I think, what International Men’s Day is for. Allowing a space, a day a year, where it is permissible to think about the tension between liking being a man, and finding that one’s masculinity can be toxic, can be threatening, and can stifle people one wants to support.

[1] Trans (short for transgender) means having a different gender to the one assigned at birth. Cis (short for cisgender) means having the same gender as the one assigned at birth.

Blog written by Graeme A. Forbes, Lecturer in Philosophy, University of Kent.

Speak Up

Speak Up Challenge yourself and Learn More

Challenge yourself and Learn More

Mentor Junior Staff

Mentor Junior Staff Challenge Your Unconscious Bias

Challenge Your Unconscious Bias Get Actively Involved

Get Actively Involved

It’s 9pm, the kids are asleep, there’s a tonne of work to be done, the kitchen has the remnants of three rushed meals on every surface, the lounge is cluttered with toys and cardboard designs and the smallest bits of shredded paper that only a hoover will pick up. Your back aches from sitting at the uncomfortable kitchen table on your laptop and you really should do some yoga to wind down and tidy up all the mess from the day. There are 7 missed calls from your mum and 45 unanswered WhatsApp messages from family and friends. You dive in between the dishes to make a G&T and fall asleep in front of the telly, feeling sad that you once again didn’t manage it all.

It’s 9pm, the kids are asleep, there’s a tonne of work to be done, the kitchen has the remnants of three rushed meals on every surface, the lounge is cluttered with toys and cardboard designs and the smallest bits of shredded paper that only a hoover will pick up. Your back aches from sitting at the uncomfortable kitchen table on your laptop and you really should do some yoga to wind down and tidy up all the mess from the day. There are 7 missed calls from your mum and 45 unanswered WhatsApp messages from family and friends. You dive in between the dishes to make a G&T and fall asleep in front of the telly, feeling sad that you once again didn’t manage it all.