Our module ‘Intervention at Historic Sites’ gives our students the opportunity to learn from recent projects of adaptive reuse, which aim to breathe new life into seminal historic buildings. Examining intervention projects elsewhere plays a key role in developing the knowledge and methods required to tackle the challenges of this module. On 14 March, we visited the church of St. Mary the Virgin at Willesborough near Ashford to explore the recent work carried out by Lee Evans Partnership. Nicholas Lee Evans, managing partner and the architect of this project provided us with a detailed presentation of the recent intervention at the building, which included the installation of a new floor, and the creation of new indoor facilities that aim to breathe new life into the building, supporting its role as a centre for the local community.

Exploring the Vaults of Canterbury Cathedral

On 10 November 2021, the students of the MSc in Architectural Conservation of the University of Kent enjoyed an unusually close view of the vaults of Canterbury Cathedral, with the guidance of Purcell engineers as well as the managers and conservation specialists of the Canterbury Journey project. The scaffolding and deck inside the nave provided a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to observe the late-Gothic lierne vaults and their rich sculptural ornamentation. Dating back to the late 14th century, and associated the work of Henry Yevele these wonderful ribbed vaults constitute a feat of engineering and one of the masterpieces of vaulted architecture.

The students of the MSc in Architectural Conservation (Kent) on the ‘vault deck’ inside the nave of Canterbury Cathedral, November 2021

Leaving the vault deck, we moved to the top of the western towers, which gave us the chance to examine the recent preservation of pinnacles and louvres in a part of the structure that is exposed to particularly harsh weather conditions. Closing with a panoramic view of Canterbury, this visit has been one of the highlights of our programme this year.

The students of the MSc in Architectural Conservation visiting the western towers of Canterbury Cathedral, November 2021

Exploring Chatham House in Rochester, by Rebecca Lilley and Diane Harvey-White

During the Autumn Term, our students visited a number of Historic Sites. Rebecca Lilley and Diane Harvey-White report on the site visit in Rochester.

It was on a bright day in mid-October that I and my fellow Architectural Conservation students arrived at Chatham House in Rochester. This Grade II* listed mansion dates from the early 18th century and has a brewery complex behind, which stretches to the banks of the River Medway. For many years and until the early 2000s the site was used as a furniture and upholstery department of the well-known Featherstone’s Department stores. In their heyday Featherstone’s had shops in Rochester, Sittingbourne, Sheerness, Gravesend, Maidstone and Canterbury, and visiting the long, nearly straight, High Street I could picture how key this institution must have been to the character and popularity of the High Street. Sadly, like so many of our department stores of old, Featherstone’s is no more. However Chris Featherstone still owns No. 351 Chatham House in Rochester. We were greeted by Chris’s daughter Sheila, who is currently managing the conservation and refurbishment of No. 351. She spoke about her plans to restore the building so that it may, once again, be accessible to the public. The plans will be multi-phased, as different areas of the site will require different treatments to bring them back into full occupation.

Figure 1 Chatham House, front elevation

From my view as a new student in conservation, the site was a goldmine of historic features, and although the buildings here have been vacant for some time, it is clear that with good planning, sound advice and a great deal of financial backing, the enthusiasm which Sheila, her family and the team on the ground show will, in time, result in a remarkable transformation from a vacant store to a veritable asset to the town. Whilst the mansion is in relatively good condition, and retains many of its original features – as is evident in its Grade II* status – it is the Brewery building that will require the most work to give it a long-term viable future. It was clear that the Brewery had evolved organically over several generations. Its interior is a maze of rooms which vary from a vast 3-storey covered yard to small store rooms and passageways on split levels. The building is a hotchpotch of different materials, some showing signs of former use, perhaps in other buildings or maybe in shipping. Roofs have cleverly been adapted over time as new rooms have been created in the nooks and crannies between the main spaces. Original features such as high-level gantries, sliding doors and winches are numerous and will aid in the retention of the aura of the brewery when it is repurposed in due course.

Figure 2 Side elevation, showing the Lion Brewery entrance

Enough of the original charm of the mansion and its brewery have been retained under the custodianship of the Featherstones and this shall aid their endeavours to retain, conserve, and repurpose the building so that it may be enjoyed for many generation to come. Our visit, which I could so easily write several more pages on, was an excellent example for the topic of our Masters and I wish Sheila and the project team all the very best for their endeavours there. It won’t be easy, but it will indeed be worth it.

Rebecca Lilley

To some people looking at a building with visible signs of decay is an uncomfortable experience; to a conservationist it is the beginning of a journey that will reveal the secrets of a building and end with that building saved for future generations. On a recent field trip to Rochester High Street, a recipient of a High Street Heritage Action Zone grant, we were able to see for ourselves one such gem – Chatham House. This magnificent town house shows obvious signs of deterioration: the front portico is missing, the façade is delaminating, there are plants growing out of the parapet. These things mask the significance of a building that contributed much to the High Street when times were good and it is this significance that informs the need for protection.

Discovering why a building becomes vacant sometimes tells the story of the wider area: the downturn in the economy, or the change in the usage of buildings in that area and this is true of Chatham House, which was used for many decades as a department store. Changes to retail shopping and the rise of the Internet, contributes to the story, for High Streets up and down the country have been victims of the same circumstance.

This mesmerising building offers the potential for events, retail or hospitality. The ancillary buildings that once housed a brewery – the house was built by a brewer as a display of his wealth – create a much larger, flexible use space to the rear and this whole site links back to the river and Chatham Docks, paving the way for a meaningful contribution to the regeneration of the area as a whole. Seeing a building in this condition offered insight to the valuable contribution important local buildings can provide for future development.

Diane Harvey-White

Studying Architectural Conservation in Kent, 2020-2021

Having commenced my career as an apprentice joiner way back in 1986, I had always appreciated the historic built environment. During the long career that followed I was fortunate to work predominantly on historic buildings, manufacturing bespoke joinery products such as Georgian and Victorian shopfronts, period doors and entrances, boxframe windows and shutters, geometric timber staircases, and an eclectic mix of traditional period fitments for both domestic and commercial historic properties.

Despite having progressed to management, and having established my own successful manufacturing business, a passion for architectural design led me to change direction following the completion of a building surveying course. This was the first step towards becoming a Chartered Architectural Technologist and towards undertaking a qualification in Architectural Conservation. The MSc Architectural Conservation course at the University of Kent had appealed to me previously, as its flexible part time option would have allowed me to maintain my design and consultancy work. However, finding the right time to commit to two year part time study was constantly frustrated by work and personal commitments.

The 2020 Covid-19 Pandemic impacted hard on my business which resulted in an immediate downturn and left a void that would have been difficult to fill in the uncertain times that followed. Therefore, I took the decision to turn the negative into a positive and reverse the plan I had been considering by undertaking work on an enforced part time basis and to embark on study full time. This has turned out to be the best decision I have made throughout my long career and has already opened up doors to a new career path which compliments my existing skillset, and which will provide the practical experience to consolidate the theoretical knowledge the course provided.

Although I was confident in my abilities I had not undertaken academic studies for several years and this had been one of the hesitations that had prevented me taking the plunge previously. Having now completed the full time course I realise that these hesitations should not have been a barrier as the lecturers were understanding, supportive, extremely knowledgeable, and managed to push you out of your comfort zone to achieve results and realise potential. This said, the course is extremely comprehensive and demands a large degree of self-discipline and dedication to complete the four modules and dissertation successfully. However, the hard work is worth it as it is an extremely interesting and knowledgeable course which is accredited by the IHBC as meeting all recognised competences.

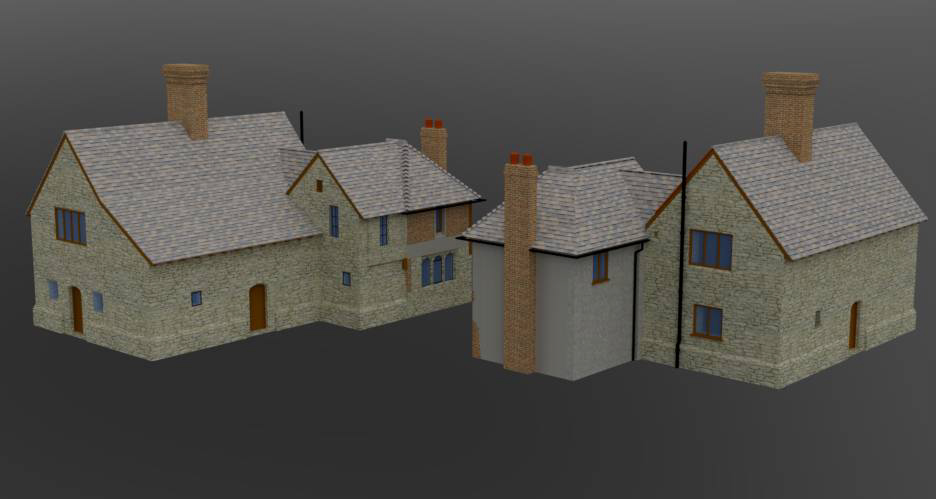

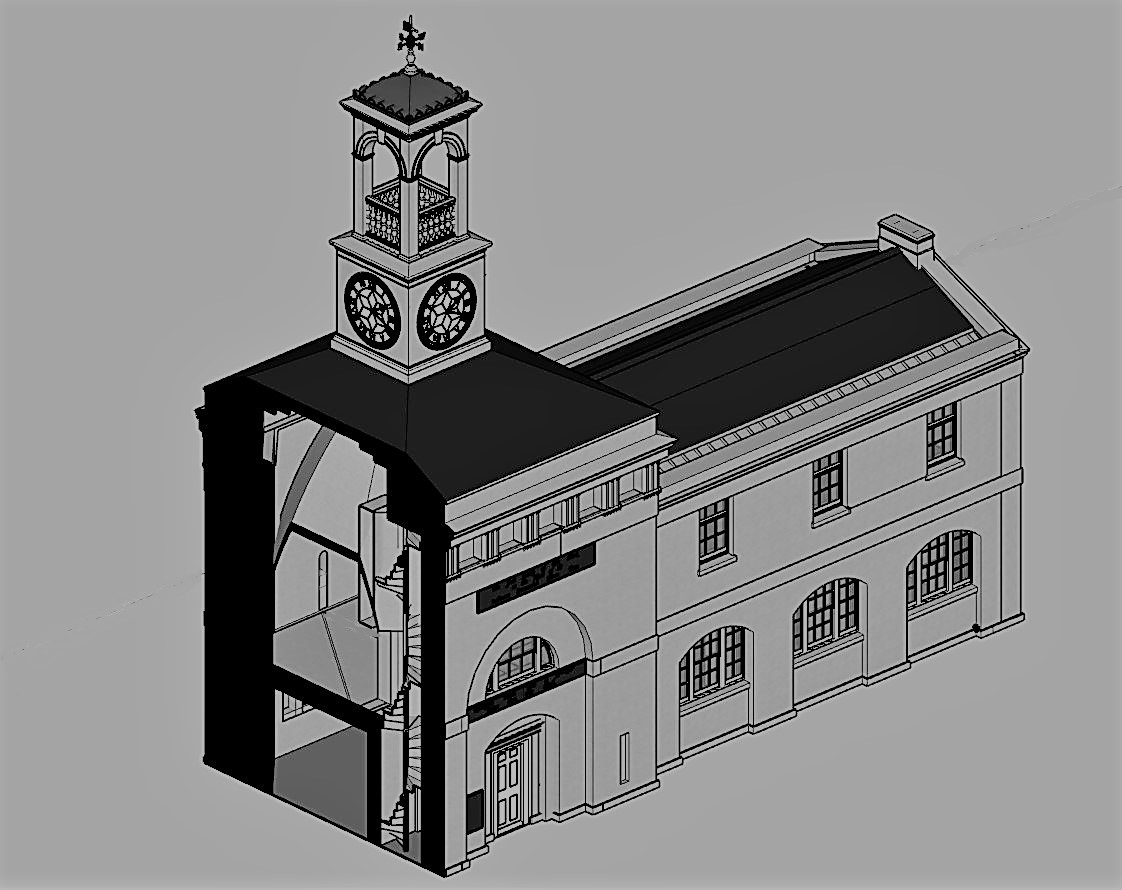

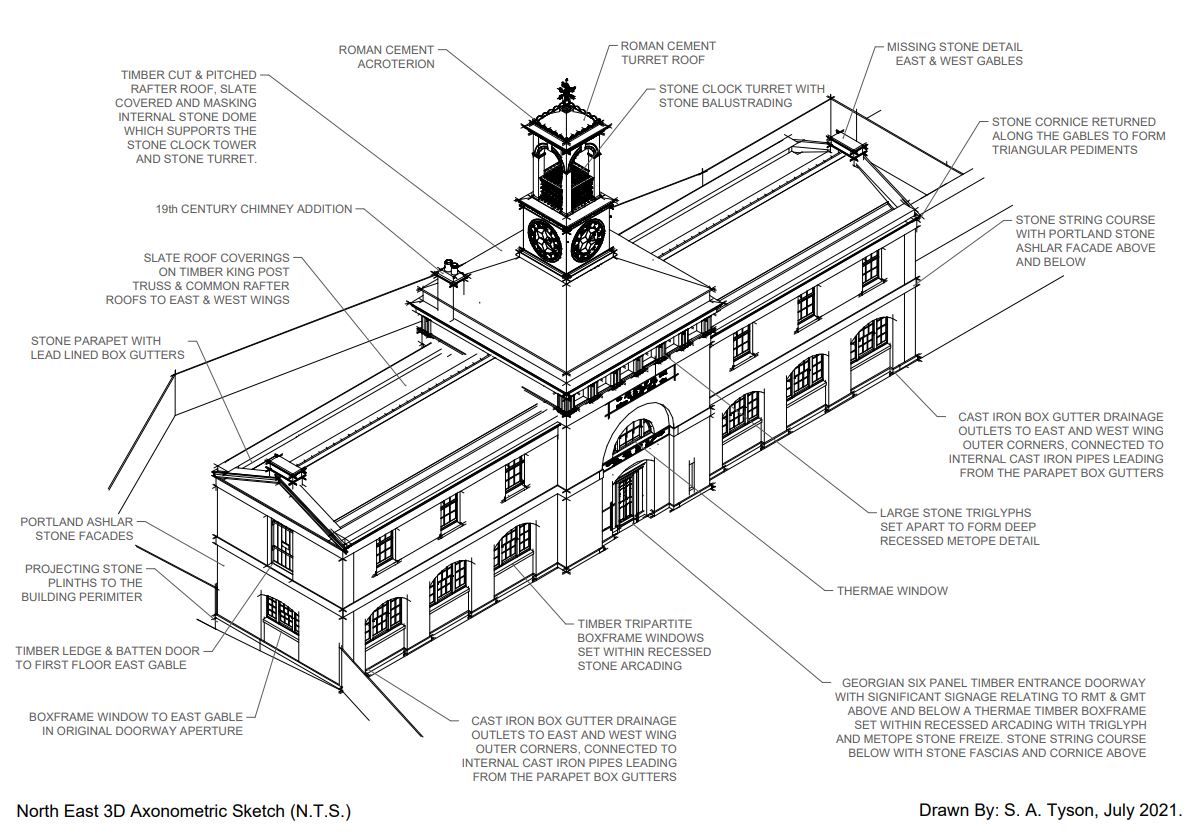

Modules on Heritage Legislation, Conservation Principles, Intervention, and Structural Appraisal provide a holistic understanding of architectural conservation which provided the theoretical knowledge to undertake the end of year dissertation. Having completed modules on the conservation areas of Herne Bay, Somerset House, Northgate, and St Andrew’s Chapel Boxley, I chose the Neo-Classical Clock House building at Ramsgate as my case study building for the dissertation. This proved to be an extremely enjoyable project, especially as I was encouraged to undertake a combination of a theoretical topic and a design proposal. The project used the Clock House building as it is currently on Historic England’s Heritage at Risk register and is in an area facing socioeconomic challenges. This provided an opportunity to analyse the effective use of Conservation Management Plans as well as developing the skills learnt through the course. This included historical research, how the building was designed and its development, site surveys and documentation, identifying levels of significance and mapping the buildings condition, preparing a statement of significance and discussing policies and strategies that would prevent further harm occurring and promote its significance and viable use to attract investors.

I would thoroughly recommend this course to anyone interested in architectural conservation or those who have an appreciation of the architectural form found within the historic built environment. It is a demanding course but the enjoyment offsets the hard work required, and I am sure you will not regret the decision to enrol!

Steven Tyson, 2021

Steven Tyson, student of our MSc Programme in Architectural Conservation reflects on his recent Conservation Plan for St. Andrews Chapel Maidstone

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings and St Andrew’s Chapel

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) purchased St Andrew’s Chapel in the winter of 2018, following its successful negotiations and proposals to rescue the Grade II* listed building which was in a derelict state and languishing on Historic England’s Heritage at Risk Register. This purchase has provided the SPAB with a perfect opportunity to promote their approach to conservation, which remains firmly based on the minimal intervention approach set out in William Morris’ inaugural manifesto of 1877. The building, which has witnessed many alterations and additions over its five centuries of history, has a wealth of evidential, historic, aesthetic, and communal significance. Despite its high intrinsic and extrinsic values, no-one could have predicted in 2018 just how valuable this building would prove to be as an educational resource following the 2021 Covid-19 lockdown.

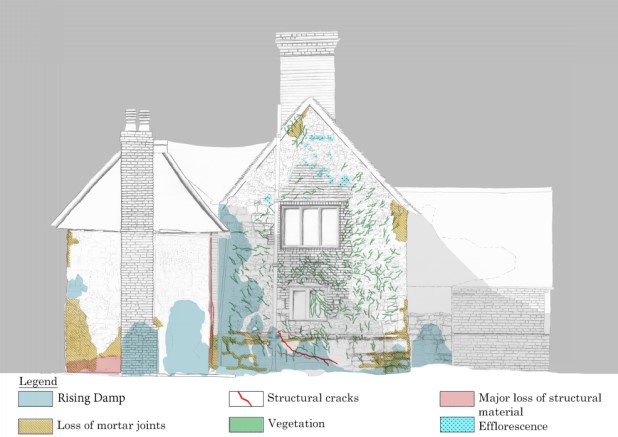

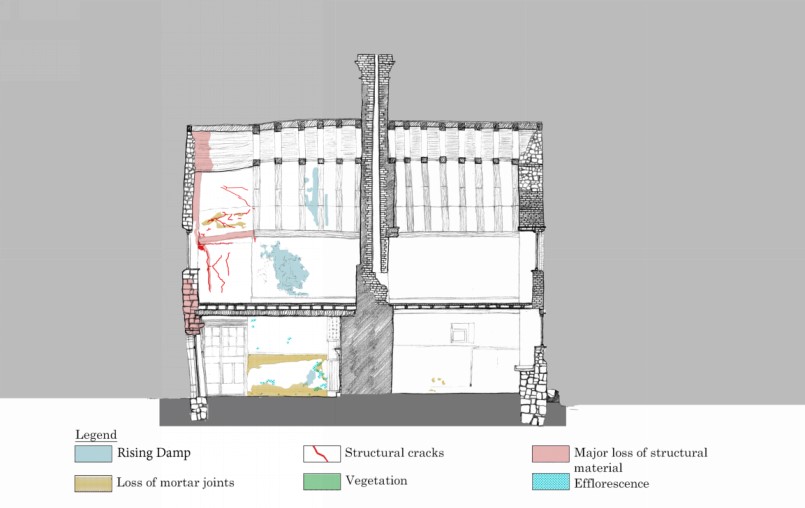

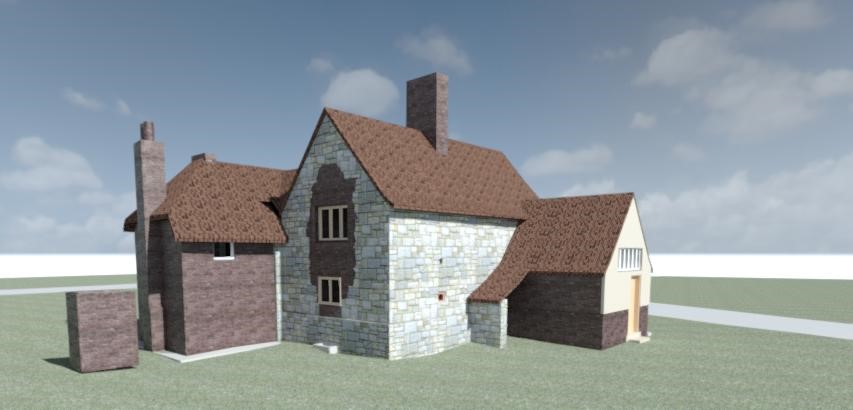

The generosity the SPAB extended to the University of Kent included an introductory informative lecture, use of pre-existing laser scans, architectural drawings, photographs, and other associated documents of St Andrew’s Chapel. The information proved sufficient for decay mapping drawings to be produced of the exterior and interior of the building, as well as enabling three-dimensional axonometric drawings of the building to be produced. The wealth of available resources ensured that the Intervention at Historic Building module could go ahead as an entirely online solution to the problems created by the 2020 pandemic. Students embraced the situation and produced some extremely impressive work which included tracing the building’s history, mapping the building’s condition, documenting its significance, and proposing a sustainable new use for the building for both present and future generations. The SPAB were extremely impressed with the extent, variety, and quality of the work, when invited back to watch a number of presentations conducted by the students.

The proposals for new use of the building, which may well have been a fifteenth century Cistercian gatehouse chapel, provided a variety of ideas such as a gallery, museum, café, restaurant, wedding venue or a possible return to part-time residential use similar to the schemes offered by the Landmark Trust. All the presentations demonstrated a minimal intervention approach in order to protect the significance and setting of the Medieval chapel, as well as providing detailed theories on the building’s phased developments. Even though research in the building’s monastic and secular use proved to be inconclusive, the building is certainly worthy of its designation and will provide the SPAB with a valuable educational and heritage asset that present and future generations will benefit from.

Steven Tyson

Here are some excerpts of Steven Tyson’s work on this module:

St. Andrews Chapel in the late-15th Century, Reconstructed Axonometric Views

St. Andrews Chapel, converted to a dwelling after the Dissolution of the Monasteries (mid-16th Century view).

St. Andrews Chapel, Intervention Proposal

The SPAB shares its 3D Laser Scan of St. Andrews Chapel with the students of the MSc Programme in Architectural Conservation

This year’s module ‘Intervention at Historic Buildings’ was delivered in collaboration with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), and gave the students the opportunity to develop a conservation plan for St. Andrews Chapel in Maidstone. To help the students document the building, the SPAB generously provided access to its laser scanning survey of the building. Shown here, this model became the basis for this year’s student projects.

St. Andrews Chapel, Maidstone. Laser Scanning produces images of extreme accuracy and detail.

St. Andrews Chapel, Maidstone. Laser Scanning produces images of extreme accuracy and detail.

This survey technique produces models that provide considerable information about historic buildings and their condition.

This model constitutes an invaluable record of the buildings current condition and makes it possible to investigate the cause of its decay.

The south elevation of the Chapel present us with a ‘palimpsest’ of different phases. One of the students’ tasks was to retrace these phases and propose their own interpretations of the history of the building and its transformations through time.

View of the chapel’s late-19th-century extension.

Laser scanning models can form the basis for accurate depiction of historic buildings in plan. They also help to document the buildings’ interior.

Repairing a Late Medieval Chapel: Learning from the ‘Old House Project’ of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) – Rosalind Webber

St. Andrews Chapel, South Elevation (drawing by Rosalind Webber, 2021)

For the last two years, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) has been surveying and repairing St Andrews Chapel, near Maidstone. Converted to a house after the dissolution, the fifteenth-century chapel is a monument of great rarity and significance, but after decades of neglect it is now in an advanced state of decay. Having recently purchased the building, the SPAB is working to determine the best ways to preserve, conserve and develop the building for future use whilst still retaining its cultural significance to its surrounding area.

I was introduced to the SPAB through The University of Kent, where I am currently finishing my Masters in Architectural Conservation. In 2020, I visited the site of St. Andrew’s Chapel and had a guided tour by Matthew Slocombe and Jonny Garlick around the site. Having only just been uncovered from numerous layers of vegetation, St. Andrew’s lay in a sorry state. Damp had penetrated into the mortar, cracks were appearing in the masonry, and most worryingly of all, the west wall was bowing outwards at an alarming angle. Having already commenced with vital repairs and monitoring and ensuring the building was secure from vandals, the SPAB have been working around the clock to ensure the survival of the building, while using it at the same time for education purposes, documentation and apprenticeships.

In the summer, armed with masks, anti-bacterial, and sun cream, I joined the team at Boxley Abbey in their first socially distanced Working Party. The SPAB rely on the enthusiasm of heritage experts, students and hobbyists to volunteer their time and help bring their projects to life. With fourty people socially distanced on the sites of Boxley Abbey, a Cistercian Monastery founded in 12th century (now a ruin) and St. Andrews, Chapel, the atmosphere was alive with people sharing stories of heritage buildings they had worked on and techniques they had used to sympathetically repair and restore them for future generations.

St. Andrews Chapel, repair of the roof (photo by Rosalind Webber, 2020)

Whilst at the working party, I prepared bricks ready to be laid in a wall by sanding them to uniform size and shape, reconstructed a part of the abbey rubble wall, repointed brickwork on the inner wall of the abbey precincts and witnessed the burning of lime in the site’s bespoke lime kiln! After a tour of the work taking place on St. Andrew’s roof, we explored the newly discovered sewage system (no longer in use) that connected various buildings within the abbey.

As part of the MSc in Architectural Conservation, we are surveying and documenting St. Andrew’s Chapel, taking into consideration the materials used in the construction. We are also identifying the different phases in the development of the building, and will soon develop a conservation plan to ensure the building is functional for future generations.

This includes creating numerous elevations, sections and plans to determine the overall condition of the building. Different sections of the building are constructed out of different materials and this is a key indication into the phasing of St. Andrew’s. As a result, phasing plans, and drawings need to be made to illustrate what the building may have looked like at different stages throughout its history.

Unravelling the wonder that is St. Andrew’s has been puzzling and challenging, but to the most part a true joy and I look forward to working with the SPAB in the future.

St. Andrews Chapel, repair of the roof (photo by Rosalind Webber, 2020)

Thoughts from a Medieval Chapel – Studying Architectural Conservation at Kent

When I joined the MSc course of Architectural Conservation at the University of Kent, I didn’t know much about British heritage and practice. Driven by my passion for historic sites, I came to discover astonishing architectural styles and historic preservation practices and philosophies. The ‘Conservation Principles’ module confronted me with some tricky questions. Should a historic building be saved partially or totally? Why do we care about its preservation? When was the building destroyed and what has been lost? How should we preserve? I soon realised that answers based only on personal views and culture can be biased… Only by studying the cultural, geographical, socio-economic and political context of a historic building can we really understand its significance and proceed to restoration.

There are different attitudes to conservation. It was fascinating to compare philosophies as different as those of Violet le Duc, John Ruskin, Cesare Brandi, and Camillo Boito, as well as conservation charters such as those of Venice and Athens. In addition to conservation philosophy, the programme introduced us to historical societies, charities, trusts, funding bodies and community involvement regarding heritage. I realised that besides understanding the UK planning system, one should be familiar with the work of amenity societies and funding bodies. After all, successful historic preservation in the UK lies in the combination of a robust legislation with the work of societies such as the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) and the Victorian society, organisations such as English Heritage, and funding bodies such as the Heritage Lottery Fund.

After this initial focus on policies, laws and philosophies, it was time for action… I was very excited to hear that the Spring Term module ‘Intervention at Historic Sites’ (January through April) would be delivered in collaboration with the SPAB and would be based on the Society’s ‘Old House Project’, the preservation of St. Andrew’s Chapel, near Maidstone. Alas, I missed the first guided visit to the chapel. Visiting it a few days later with a classmate was one of most exciting moments of the programme. This was a unique chance to experience an unspoiled medieval building, which is very little known. Formerly part of the Cistercian Boxley Abbey, the chapel was converted into a dwelling in the 16th century. Abandoned for decades, the chapel is now in an advanced state of decay, but is not entirely derelict. Some of its features, such as the late-Gothic mullioned window, the Tudor chimneys, the post-dissolution half-timbered extension, and the early 20th-century fireplaces survive and reveal the complex history of the building.

Drawing the chapel, looking at its decay, retracing its history, and reflecting on repair methods was rewarding, and designing a proposal of adaptive reuse added to the pleasure… Here are some samples of my analysis of the decay of the chapel:

I look forward to visiting the site again, to take a long walk through the narrow pilgrims’ way near All Saint’s Church. I will then follow Boarley Lane from which I can enjoy the scenery around Boxley Abbey’s gate. I will admire the mysterious remains of the Cistercian monastery, particularly its medieval Barn. After another visit of the monastery garden, I will return to Boarley Lane and St Andrew’s Chapel, which lies just before the motorway, waiting for its repair.

Visiting Canterbury Cathedral

Recently, the students of the MSc in Architectural Conservation visited Canterbury Cathedral. Our student, Chandler Hamilton writes: We had the chance to tour the sections of the Cathedral that are under repair. All these areas are normally unavailable to the public. I focused on Gothic Architecture in my undergraduate degree, and for me, this was a unique opportunity to get a behind-the-scenes tour of a structure that I have studied intensely in the past. The tour started off with meeting the Head of Conservation and Site Manager, Heather Newton, who basically has my dream job! She gave us an introduction to the conservation project and an itinerary for the day. The project that started in 2016 and is set to finish around October 2021 is a 25-million-pound development that is focusing on the roof of the cathedral.

We went all the way up to the top of the scaffolding on the western towers and saw a breath-taking view of the roof and the city of Canterbury. At the top you can see the difference in each piece of stone by how eroded it is. Since the cathedral was first developed, stone has been replaced throughout each century. One interesting fact that I did not know was that in the early-20th century, there was a shortage of materials and funding, so the builders created stone-like blocks out of cement instead. There is a course on the northern side of the cathedral where you can visibly see the cement.

We then moved down into the top of the nave where they are currently repainting the ribbed vaults and sealing off cracks. Not only was this the closest I have ever been to ribbed vaults and could clearly see every detail, but there was also an incredible view of the choir to look out to.

The last stop on this tour was the inside of the roof to look at the timber structures that are supporting the buttresses. Each piece of timber is extensively investigated for any signs of decay, rot, or damage, then decided on if it needs to be replaced or not. They are trying to preserve as much of the Victorian wood as possible, so they only replaced the end where two pieces connect.

Restoration of St. Andrew’s Chapel, Maidstone (in Collaboration with the SPAB)

This year, the SPAB (Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings) has given our students the opportunity to work on a live project in ‘St. Andrew’s Chapel’, near Boxley Abbey, Maidstone. Built in the 15th and the 16th century and modified in the 19th century, the ‘chapel’ is currently in an advanced state of decay. The SPAB is currently surveying the building with the view to restore it. Our students visited the site several times and were guided by SPAB specialists. SPAB Director Matthew Slocombe introduced the Society’s work and project officer Jonny Garlick surveyed the building with the students and gave us an unforgettable tour of Boxley Abbey, focusing on previous SPAB repair work. During the Spring Term, the students will prepare a conservation plan, engaging in tasks that reflect their individual backgrounds. Those with an architectural background have the option to design the adaptation of the building into a new use. Students with backgrounds in other fields have several options which include researching the building’s history, analysing its significance and drafting conservation strategies. The resulting work will be submitted to the SPAB with the aim to contribute to the future conservation of this magnificent building.

For further information on the SPAB’s current ‘old house project’, see: https://www.spab.org.uk/old-house-project

Nikolaos Karydis, 22 February 2020