As the refugees sheltering in the ‘Jungle’ camp in Calais await its demolition, the British government finally announced its intention to permit migrant children with family in the UK to enter the country.

Listen to the BBC Radio 4 segment about the announcements made in Calais, here.

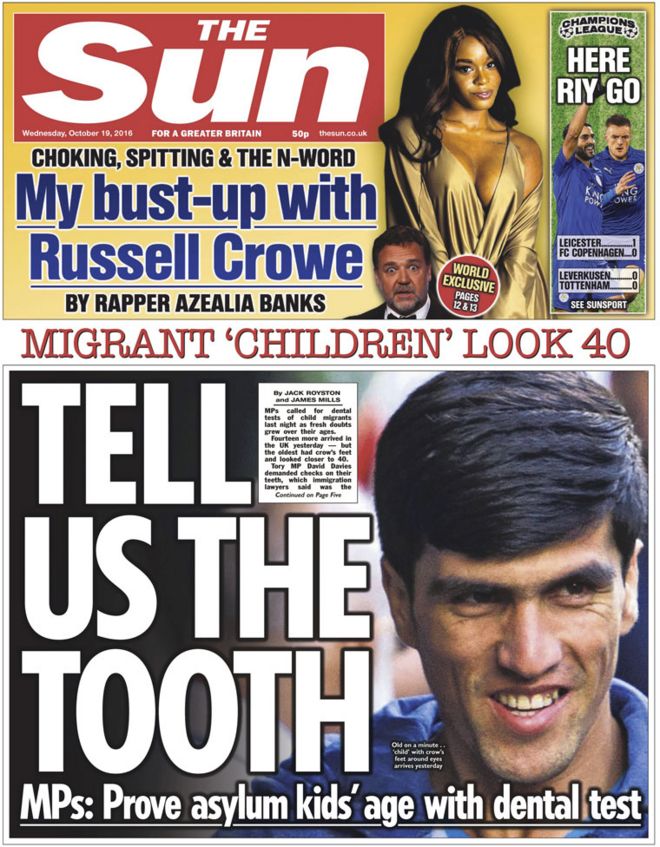

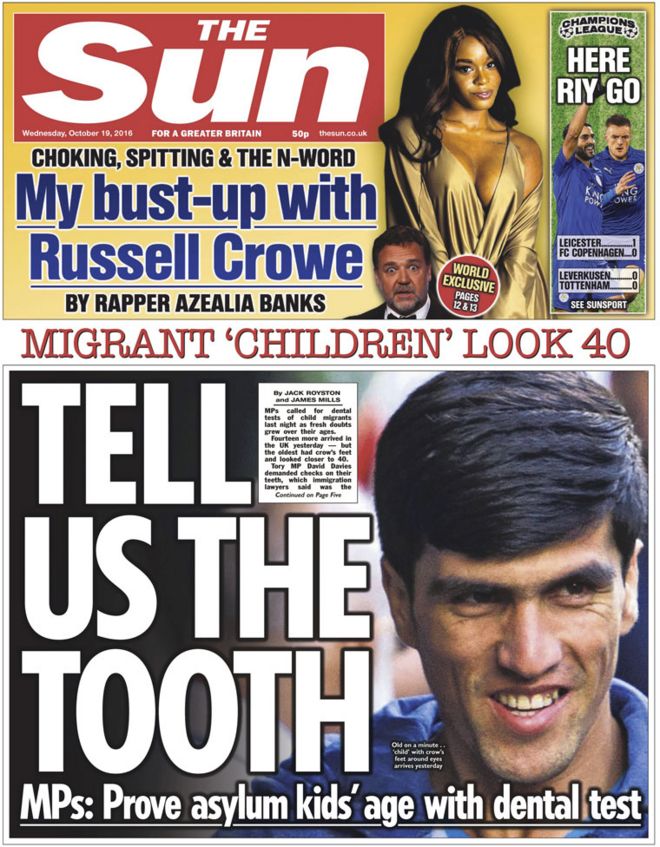

The Sun newspaper echoes Conservative calls for ‘dental tests’ to prove the age of the migrants.

However, the move is being challenged by Conservative MPs and media. For example, David Davies MP tweeted;

“These don’t look like “children” to me. I hope British hospitality is not being abused.”

This challenge rests on the notion that only children (defined by being under 18 years of age) have the right to resettle in the UK. Biological age becomes the determining factor in assessing the right to humanitarian aid.And how is it possible to verify the status of being a ‘child’?

Opponents to the migrant resettlement have called for dental testing to ‘prove’ ages. However, these tests are often inaccurate (Listen here from 51:00 for an interview on the reliability of the practice) and the British Dental Association has firmly voiced their opposition.

Anthropologist Susan J Terrio investigated a similar policy approach in France, where officials use a controversial bone development assessment to determine the ages of undocumented minors. The consequences of ‘failing’ such biological tests are catastrophic, as she illustrates with the example of a homeless Gabonese minor, who was identified as a legal adult as a result of the skeletal development and served a year in an adult prison at the age of sixteen. (1)

This is not the first time the British government has resorted to inaccurate biological signifiers of ‘childhood’ in order to apply a humanitarian policy. The British slave trade abolitionist movement was animated by concerns over the impact of the slave trade on children. (2) One of the earliest pieces of legislation aimed at ameliorating the the conditions for enslaved people was Dolben’s Act (1788). This act limited the number of people that could be transported aboard British Slave Ships. It defined a ‘child’ slave as those “who shall not exceed four Feet four Inches in Height”. Because the act was primarily concerned with the issue of space; it decreed that “If more than 2-5ths of the Slaves be Children, 5 of the Surplus to be deemed equal to 4 Slaves.” That meant that slave traders could take more enslaved people aboard, provided they were under 4’4″ and presumed to be children. Colleen Vasconcellos argues that this was responsible for an increased proportion of children being take up into the trade.

This marker of 4’4″ was taken up in subsequent legislation relating to enslaved children. It defined children on slave plantations in the Caribbean and missionary schools in early colonial Sierra Leone. Despite the obvious problems with it as a universal tool, because height varies greatly not only with age but also with health, particularly the effects of malnutrition, ethnicity and gender.

Other means were also used, in the Indian Ocean slave trade for example, an ‘estimate of maturity’ was used alongside the individual’s own perceived age. (3) This kind of reckoning left considerable scope on both sides for fudging the dividing line.

Being defined as a child didn’t always offer extra protection from exploitation or harm in the British Empire. Sometimes, children were targeted as a cheap and easily controlled labor source. For example, ‘destitute children’ were forced to serve as indentured servants by the government of the Cape Colony in the latter half of the 19th century. (4)

The question of defining childhood is a complicated one — and an extensive historical literature has emerged which tackles not only the question of the shifting and contingent meanings of childhood, but also attempts to address how notions of childhood, youth and adulthood are shaped by cultural and social contexts.

The debate over ‘Who is a child?’ and how are childhood is defined had and continues to have lasting and significant consequences in the lives of vulnerable and exploited people, subject to the scrutiny or intervention of government agencies.

- Terrio, Susan J, ‘New Barbarians at the Gates of Paris?: Prosecuting Undocumented Minors in the Juvenile Court—the Problem of the “Petits Roumains”’, Anthropological Quarterly, 81 (2008), 873–901 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/anq.0.0032>

- Alpers, Edward A, ‘Representations of Children in the East African Slave Trade’, Slavery and Abolition, 30 (2009), 27–40 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01440390802673815>

- Campbell, Gwyn, Suzanne Miers, and Joseph C Miller (eds.) ‘Editors’ Introduction’ pp. 1-18 in Children in Slavery Through the Ages (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2009)

- van Sittert, Lance, ‘Children for Ewes: Child Indenture in the Post-Emancipation Great Karoo: C. 1856–1909’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 42 (2016), 743–62 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2016.1199394>