Dr Shannon Toll (University of Dayton)

On July 3, 1950, the newly-minted New York City Ballet, helmed by celebrated choreographer George Balanchine and his prima ballerina and wife, Maria Tallchief, boarded a plane to travel to London for a five week season at the Royal Opera House in the heart of Covent Garden. The pomp and circumstance of such an invitation notwithstanding, London was still rebuilding after World War II, and with food rations still in place, most company members had packed provisions to either supplement their own meals or for their friends abroad who were unable to get certain food items. Not so with the company star, Maria Tallchief, who boarded with a “few boxes of chocolates to tide her over during the pinches,” and her fellow ballerina, Janet Reed, who “took only two cartons of cigarettes,” claiming that “if the British could get by on their food rations, so could she.”[i]

The fledgling company was used to making it work in face of adversity, after two years of costumes arriving minutes before curtain calls and constant threat of financial ruin. Fortunately, their second season garnered consistent praise from critics and featured Balanchine’s triumphant restaging of Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird, which catapulted the company and its star Tallchief, America’s first prima ballerina and a member of the Osage nation, into the spotlight. It was the production that cemented their reputation as “the most significant manifestation of ballet in the United States,” and caught the attention of the Arts Council of Great Britain, who extended an invitation to New York City Ballet to perform a season in London.

It was understood among dancers and management alike that their London engagement would make or break the company, so when they boarded that plane, having been rehearsing all summer, they knew that failure was not an option. In her autobiography Maria Tallchief: America’s Prima Ballerina, Tallchief writes about her apprehension of representing not only herself, but the company and the future of American ballet on an international stage. Tallchief had danced on Europe’s most illustrious stages before, including joining the ranks of danseuse étoile (feminine “star dancer”) in the Paris Opera Ballet, but now in her “position as the company’s leading ballerina, and as Balanchine’s wife, much was depending on [her].”[ii]

Moreover, the company’s stability was contingent on her successful partnership with Balanchine, and they had hit a snag in their marriage. While Tallchief relished her artistic relationship with Balanchine, their personal life was not marked by passion or romance, and Tallchief had recently fallen in love with Elmourza Natirboff, a charming pilot she met through a friend. Unbeknownst to Tallchief, Balanchine was shifting his attentions to Tanaquil Le Clerq, a budding star in NYCB, whom he would later marry, as he did all of his “muses.” When Tallchief divulged her interest in Natirboff, Balanchine was not angry that she wanted to leave their marriage, but worried that the English tabloids, which he referred to as “gutter press,” would sensationalize their personal relationship at the expense of the company[iii] The couple decided to divorce once they returned to New York after their London engagement, and proceeded as if everything was normal to present a unified front to audiences and critics.

As a prima ballerina and a Native American woman, Tallchief had a lifetime of experience with confronting dominant expectations about her talent and identity, and knew when to push back and when to demur. Born in Fairfax, OK to Alexander Tall Chief (Maria combined her surnames early in her career) and Ruth Porter Tall Chief, she and her sister Marjorie were precocious performers from a young age. Her mother was determined to make them stars, placing them in piano lessons and dance classes, while her father, a member of the Osage Nation, would take the girls to secret powwows in “remote corners of the reservation,” where the Osage could practice ceremonies and rituals that were banned at the time.

Her journey to the stage began with dance and tumbling classes taught by itinerant (and unprofessional) teachers in Fairfax; the family then traveled to Los Angeles, where she had access to skilled teachers for the first time but also was met with suspicion by her white classmates, who would war whoop when she walked by and asked if her father “took scalps.”[iv] She danced at the Hollywood Bowl at 15, and appeared as an extra in a Judy Garland film before traveling to New York. There, she joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and toured North America and Europe, honing her technique and rising through the ranks, much to the chagrin of many of her fellow Russian ballerinas. It was through Ballet Russe that she met the man who would become her choreographer and husband, George Balanchine, and together they were the artistic force beyond Ballet Society, Inc., which would later become New York City Ballet, America’s first significant ballet company.

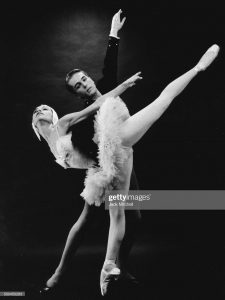

With Tallchief as his muse, Balanchine would tailor the choreography to fit her strengths and particular talents, such as her innate musicality and her tumbling background, which led to the creation of some of his most celebrated ballets, including Firebird, the role of the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker, and Symphony in C. Throughout her career, Tallchief confounded her fellow dancers and audiences alike, who were skeptical that an American, let alone a Native American woman could achieve the heights of European and Russian performers such as Alexandra Danilova, Margot Fonteyn, or Anna Pavlova. As NYCB’s prima ballerina and a rising star of the ballet world, the expectations were high.

WATCH: Tallchief performing Firebird at Jacob’s Pillow here.

Rehearsals in London commenced, and while the cultural significance of Covent Garden was unparalleled for the company, the stage was another story. According to Tallchief, it was studded with splinters and featured a “slight incline from the footlights to the upstage area,” which was great for the audience to take in all of the action, but difficult for dancers who were not used to it. NYCB was to present their most popular ballets, including Firebird, Symphony in C, and Bourrée Fantasque, all of which heavily featured Tallchief in challenging, diverse roles. The opening night “was a major event in the world of international ballet,” as the audience was populated by elite society, including members of the British aristocracy and celebrated dance critics.

Unfortunately, disaster struck early in the evening. During one performance, as Tallchief moved into an arabesque (a posture in which the dancer is supported on one leg, with the other leg extended behind the body, both legs turned out), the “power drained out of the foot I was standing on, the right one, and it collapsed under me.” Tallchief had badly sprained her ankle, but managed to finish the ballet. Backstage, the company doctor tried to dissuade her from dancing the remaining ballets of the evening, but Tallchief was determined to dance in Symphony in C, but was in too much pain to continue, and was replaced by Melissa Hayden, a decision that was necessary but made her “heartsick.”[v]

Despite Tallchief’s injury, the opening night was still successful, and while some critics noted Tallchief’s departure and the company’s apparent “nervousness” in the opening numbers, audiences were impressed by the company’s presentations of classical ballet and the “distinctively American” Age of Anxiety, which displayed a “vivid miming of the strains and stresses of modern life.”[vi] One critic for The Times of London noted that the company’s distinctly “American” style of dancing “may be said to be gracefully athletic, rather than gracefully poetic,” but praised Age of Anxiety for refusing the “usual pretentiousness of psychological or metaphysical offerings, though heaven knows it is unintelligible enough.”[vii] The latter ballet resonated deeply with the audience, and one would imagine that “anxiety” was apropos in a post-war London.

For Tallchief, the anxiety intensified as she nursed her injury, knowing that her trademark role in Firebird was only days away. Her ankle was still so sore that Balanchine replaced one of the signature steps, a fouetté (“whipped turn”) “that ended in an arabesque and a long pose on the right foot,” where her injury was located.[viii] Tallchief had hoped that Firebird would have the same impact it did on its opening night in New York, and on July 20, she took the stage in the titular role for the first time after her injury, and was greeted by “thunderous applause” by the audience, seemingly mirroring the rapturous reception they received back in New York.

Critics, however, found the entire night polarizing. One reviewer from The Times described the opening ballet Les Illuminations to be “a study in decadence, chic and nasty,” and “Firebird, for which London has waited long…a poor emaciated creature.” He continued, lamenting that Tallchief, who had astounded audiences back at home with her performance in Firebird, “caught some of the glitter of the bird, but none of her supernatural magic.” He ended with a withering observation that “perhaps this company is too immature for imaginative and romantic ballets.”[ix] However, the audience was enthusiastic in their reception of Firebird, and Balanchine was unflappable in the face of criticism, so the company put it behind them, with the exception of their financier Lincoln Kirstein, whom Tallchief recalls as “hysterical and unhappy” with the reviews.[x]

Fortunately, Tallchief’s ankle began to heal (though it remained sore for the remainder of their engagement) and she garnered positive reviews for subsequent performances. In Divertimento, the previously unimpressed Times of London wrote effusively of her “superb physique and eloquent movements,” dare we say finally achieving the “gracefully athletic” and “gracefully poetic” balance that had been missing in earlier performances?[xi] Overall, their season at Covent Garden was a success, solidifying the company’s reputation abroad and receiving an invitation to return for a second season in 1952.

NYCB returned to New York and Tallchief and Balanchine announced their separation and soon after married their respective love interests but continued their fruitful artistic partnership for the next decade (both would go on to divorce their new partners, and Tallchief would later marry businessman Buzz Paschen). Their “Welcome Home Season” saw Tallchief triumph onstage and in the public eye, as she became both a critical darling and a recognized celebrity. In the ensuing years, Tallchief received ecstatic reviews for her performances in revivals of The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, but also danced for other companies, including portraying legendary ballerina Anna Pavlova in the MGM production of “Million Dollar Mermaid,” co-starring Esther Williams, and returned to Ballet Russe for a season, earning a salary that established her as the highest paid dancer at the time.[xii] She returned to London on more than one occasion, eventually sharing the stage with her friend Margot Fonteyn and her sister, Marjorie Tallchief, who was a famous ballerina in Europe.

Tallchief remained with NYCB until 1965, and retired from ballet at the age of 41, noting that she had been devoted to ballet for 35 years. Not one for actual retirement, she went on to found the Chicago City Ballet, and Balanchine came to their first performance of Firebird, which Tallchief had staged. After the ballet, Balanchine spoke to Tallchief’s daughter, Elise Paschen, telling her that “’Firebird was the first big success for the New York City Ballet. Without Firebird, I don’t think there would be a New York City Ballet today. The reason it was so good is because your mother was so wonderful in it.’ He paused and turned to look at me. ‘She was absolutely wonderful.’”[xiii]

Tallchief continued to gain accolades and critical adoration, including earning the title of Princess Wa-Xthe-Thonba (“Princess Two Standards”) from the Osage Nation in 1957, the Capezio Dance Award in 1965, the Indian Achievement Award of 1967, a Kennedy Center Honors Award and was inducted to the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1996, and was awarded a National Medal of Arts in 1999. When she passed in 2013, she was memorialized by major publications as “dazzling,” “an inspiration to Balanchine,” and as America’s first prima ballerina, but it was her daughter Elise, a celebrated poet, who found the right words to capture her legacy:

“My mother was a ballet legend, who was proud of her Osage heritage…Her dynamic presence lit up the room. I will miss her passion, commitment to her art and devotion to her family. She raised the bar high and strove for excellence in everything she did.”[xiv]

[i]. “CITY BALLET TROUPE IS FLYING TO LONDON.” New York Times (1923-Current file), Jul 04, 1950, pp. 10. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/111683367?accountid=14607.

[ii]. Tallchief, Maria, and Larry Kaplan. Maria Tallchief: America’s Prima Ballerina. University Press of Florida, 2005, 140.

[iii]. Ibid, 144.

[iv] . Ibid, 144-5.

[v]. Ibid, 144-5

[vi]. Special to THE NEW,YORK TIMES. (1950, Jul 11). LONDON WELCOMES NEW YORK BALLET. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/111785804?accountid=14607

[vii]. Ibid.

[viii]. Tallchief and Kaplan, 146.

[ix]. “New York Ballet.” The Times, 21 July 1950, p. 8. The Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9bYj67. Accessed 27 Mar. 2019.

[x]. Tallchief and Kaplan, 146.

[xi]. “New York City Ballet.” The Times, 4 Aug. 1950, p. 7. The Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com.libproxy.udayton.edu/tinyurl/9bXPG6. Accessed 27 Mar. 2019.

[xii]. Anderson, Jack. “Maria Tallchief, a Dazzling Ballerina and Muse for Balanchine, Dies at 88.” The New York Times, 13 Apr. 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/04/13/arts/dance/maria-tallchief-brilliant-ballerina-dies-at-88.html.

[xiii]. Tallchief and Kaplan, 317

[xiv]. Indian Country Today. “Osage Ballerina Maria Tallchief Walks On at 88.” IndianCountryToday.com, Indian Country Today, 12 Apr. 2013, newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/osage-ballerina-maria-tallchief-walks-on-at-88–XsutztMIEisYYIVgZKKsg/.

I don’t even know the way I stopped up here, but I assumed

this post was once great. I do not understand who you are however certainly you’re going to a well-known blogger if you are

not already. Cheers!