Professor Jacqueline Fear-Segal (UEA)

Co-Investigator, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

‘Beyond the Spectacle’ is a research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The Research Council’s “Research in Pictures” scheme generously funded photographic coverage of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ participation in the 2019 London New Year’s Day Parade for this project.

This year, a delegation from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) made a dazzling appearance at London’s New Year’s Day Parade (LNYDP). Their traditional eighteenth century regalia, with British Army redcoats, war clubs, and face paint, thrilled the crowd as they paraded down Piccadilly, Pall Mall, Trafalgar Square, and Whitehall, to Westminster Abbey. Dawn Arneach, from the Museum of the Cherokee Indian, co-ordinated the trip and participated in the Parade: “The vast amount of people in the street for the Parade was great and to see so many people smiling and maybe seeing for the first time in their life a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians was thrilling.”

Dawn Arneach is correct. Few in London have ever knowingly seen a Cherokee. Although they have a long historical connection with Britain, this was the first official Cherokee delegation to travel to England for over 255 years and to appear publicly in their regalia. Their visit commemorated and revitalises a Cherokee-British relationship that dates back to the seventeenth century. In an era when European powers were rivals on the American continent, they competed to win the support of one of the most powerful and strategically significant Native nations in British America. The Cherokee controlled lands across present-day Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia, so the British were keen to foster a strong trading relationship to underpin a military partnership with the Cherokee, “Because they are a Warlike People and can bring three Thousand fighting Men upon Occasion into the Field.” The alliance was troubled and interrupted, but lasted most of the eighteenth century. The Cherokee allowed the British to build forts on their lands and fought alongside the British, wearing their British Army redcoats, during the French and Indian Wars (1754-1763) and later the American War of Independence (1775-83).

In this latter war, the Cherokee were on the losing side and the creation of the land-hungry United States was a catastrophe for them, as for all of America’s Indigenous peoples. Fifty years later, greedy white settlers had surrounded the cotton-rich lands of the Cherokee. To incorporate these lands into the United States, the government forcibly removed nearly 20,000 Cherokee to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), enabling white Americans to seize and occupy traditional Cherokee lands. This genocidal removal, or “Trail of Tears”, killed over 4,000 Cherokee. In Indian Territory, the survivors succeeded in re-organising the Cherokee Nation. However, a small group of about 800 Cherokee scattered, hid, and remained behind; many years later, they succeeded in reconvening as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

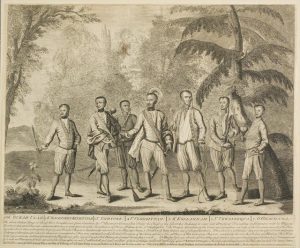

In colonial times, invitations to Native leaders to visit the centre of imperial power were integral to British colonial strategy. These visits ensured active Native American participation in the construction of global networks of power, mobility, and empire. In 1730, a group of seven Cherokee, led by Oukanaekah (aka Attakullakulla or Adgalgala) made up the first ever delegation to travel to London from southeastern North America. Their numerous audiences with King George II at Windsor Castle led to the signing of a treaty, creating a new transatlantic relationship and providing the Cherokee with an arsenal of weaponry and ammunition: “twenty gun,” “four hundred weight of gunpowder,” “five hundred pounds weight of bullets,” “ten thousand gun flints and six dozen hatchets.” In exchange, the Cherokee agreed to trade exclusively with the English (and not the French or Spanish) and promised that “in war we shall always be as one with you. The Great King George’s enemies shall be our enemies.”

In America, such diplomatic visits to England also brought personal status to Native travellers. A quarter century after his return home, Oukanaekah (seen on the right of the engraving above) boasted, “I am the only Cherokee now alive who was in England or that saw the great King George.” A few years later, in 1762, after a new treaty to re-establish the fractured peace had been signed between the Cherokee and Governor Fauquier of Virginia, in Williamsburg, Virginia, the aspiring Cherokee leader, Osteneco, expressed his determination to “visit the great King on the other side of the water”.

Osteneco’s wish was granted and he set sail with two compatriots, accompanied by Ensign Henry Timberlake of the Virginia militia, who had lived with the Cherokee for several months. Despite only knowing a smattering of their language, Timberlake had mapped Cherokee territories and believed he had “passed an apprenticeship in their ways.” Timberlake’s detailed account of the trip to England, his enumeration of the places the delegation stayed, and his descriptions of the Cherokees’ reactions, leaves a firsthand record of this delegation’s visit. His role was considered important enough for the twenty-first century Cherokee to include “Timberlake” in their own 2019 delegation! Numerous colourful reports in English newspapers and magazines augment Timberlake’s Memoirs, describing how the three men were followed everywhere by large rambunctious crowds, desperate to catch a glimpse of the Cherokee visitors and to examine every detail of their exotic appearance:

Three Cherokee Indian Chiefs arrived in London from South Carolina. They are well made men, near six feet high, were dressed in their own country habit, with only a shirt, trowsers [sic], and a mantle round them. Their faces are painted of a copper colour and their heads adorned with shells, feathers, ear-rings.

Most of the impressions the delegation made on the crowds that followed them were visual, because unfortunately, their interpreter had died on the sea voyage and so they were unable to communicate directly with the British. Nevertheless, they travelled to St James Palace to meet with King George III, to whom Osteneco delivered a prepared speech in Cherokee, pledging peace between the two peoples; the King was apparently too baffled to give a reply. For the Cherokee, this meeting was important because it formalised the recent sovereign treaty they had signed with the British in America. Osteneco ended his speech with the words, “Nigadi yyw didatsinohisel nusdv hagigohv anigaliisiyi,” translated, “I shall tell my people all that I have seen in England.” For the occasion, the Cherokee had dressed predominantly “in the English fashion,” although their “heads [were] richly ornamented”. On his breast, Osteneco wore a silver gorget engraved with King George’s arms. At the New Year’s Day Parade in 2019, John Standingdeer, aka Bullet, referenced this meeting by wearing a replica of that same gorget.

Most of the impressions the delegation made on the crowds that followed them were visual, because unfortunately, their interpreter had died on the sea voyage and so they were unable to communicate directly with the British. Nevertheless, they travelled to St James Palace to meet with King George III, to whom Osteneco delivered a prepared speech in Cherokee, pledging peace between the two peoples; the King was apparently too baffled to give a reply. For the Cherokee, this meeting was important because it formalised the recent sovereign treaty they had signed with the British in America. Osteneco ended his speech with the words, “Nigadi yyw didatsinohisel nusdv hagigohv anigaliisiyi,” translated, “I shall tell my people all that I have seen in England.” For the occasion, the Cherokee had dressed predominantly “in the English fashion,” although their “heads [were] richly ornamented”. On his breast, Osteneco wore a silver gorget engraved with King George’s arms. At the New Year’s Day Parade in 2019, John Standingdeer, aka Bullet, referenced this meeting by wearing a replica of that same gorget.

The 1762 visit is a vital part of the history of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, as Cherokee artist, Shan Goshorn, acknowledges in her work, They Were Called Kings (2013). When commemorating this visit in a set of three baskets, Goshorn chose to weave into her baskets photographs of three contemporary members of the Warriors of AniKituhwa, instead of reproducing images of the eighteenth century travellers. She makes the connection between past and present explicit when she explains, “Traditionally, men in this position would serve as the first line of defense for the Cherokee people; currently, they serve in the role of ambassadors representing the Eastern Band of Cherokee and are role models within the community.”

The Warriors of AniKituhwa led the Cherokee delegation at the London New Year’s Day Parade. As Warrior Michael Crowe (second from left in the photograph and featured on a They Were Called Kings basket) observed immediately after the Parade, “It’s hard to take on board the full significance of what we just did, walking in the footsteps of our ancestors.” For Principal Chief, Richard G. Sneed, the trip to London was life changing, because it gave an insight into the visit of those three Cherokee “kings”. “In taking it all in, I kind of put myself in their place, to imagine how it would have looked and been for those three men in 1762.” Dawn Arneach said, “To see London with my own eyes was a deep experience personally, not so much just one place, but everywhere.” And Warrior James “Bo” Taylor posted a message on Facebook for his people back in North Carolina, to explain: “We are dressing Cherokee style. I am even wearing paint on my face. I want to wear paint and it does empower me.” For Bo, and the other Warriors of AniKituhwa, their traditional clothing and face paint connects them personally and visually to their sacred traditions and past. But they are also keen to be recognised as modern, twenty-first century, selfie-taking Cherokee.

Today, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians live on just a small fraction of their former homelands in Cherokee, North Carolina, but the Warriors of AniKituhwa maintain and continue their dances, language, culture, and warrior traditions. They work to challenge entrenched romanticized stereotypes and, as they made very clear to the “Beyond the Spectacle” team when they were in London, they are impatient with the commercialization and ubiquity of Plains Indian feather war bonnets.

Actively engaging with their ancestors’ travels, the 2019 Cherokee delegation deliberately visited many of the same places. Although much of modern London was built after the eighteenth century, Westminster Abbey, the Royal Observatory, and the Tower of London were already standing in 1762, and allowed the group to tread some of the same pathways and enjoy similar tourist activities to their forbearers. Eighteenth century London had boasted more coffee houses than any other city in the western world, and the 1762 Cherokee visitors enjoyed visiting them. In the twenty-first century, dressed in their regalia and walking through the cold New Year morning on their way to the Parade, the 2019 delegation was very happy to find an open coffee shop. As Bo Taylor wryly observed, “So we all pile in and warm up and have coffee….. Pretty funny if you were to walk in and see Henry Timberlake and a bunch of Cherokee drinking coffee and eating scones.”

The Cherokee demonstrated their engagement with modern traditions when, after the Parade, they persuaded their coach driver to take them to Abbey Road; they wanted to reenact the historic crossing made by the Beatles. Such was the group’s enthusiasm, it took a little time to capture the iconic image.

When driving to their BBC Breakfast interview before the Parade, the delegation’s taxi had been stopped at one of the police barricades marking the route. Bo Taylor remembers that “the driver tells the policeman … ‘I’ve got 6 red Indians in here and we are headed to Trafalgar Square.’ He let us through, and we all have a good laugh about it.” By their very presence in England, Bo Taylor hopes that the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians have demonstrated their continuing existence and vitality; and that they are not the proverbial “red Indians.” He wants the British to be able to see beyond the spectacle of the Warriors of AniKituhwas’ traditional regalia, so that they are able to interact with and come to know Cherokee of the twenty-first century. Putting it plainly, he says, “I want them to see me in my everyday clothes, as well as my regalia.”

A week after they arrived home from the 2019 Parade, LNYDP executive director, Bob Bone, wrote to the Warriors of AniKituhwa to say, “Thank you… the 2019 parade really was the best ever. This is in large part down to your contribution.” So this year, the historic British-Cherokee relationship was revitalized, and many people at the Parade both saw and interacted with modern-day Cherokee.

Photographs are by Professional Images, courtesy of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians are Collaborating Partners of ‘Beyond the Spectacle’.

Look out for a future post about the twelve members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians living in Hemel Hempstead today!

The Cherokee and Scottish people have a long and interesting relationship. As a Scot, involved with Beyond the Spectacle project I look forward to forging links with the Cherokee. We have a rich shared history, sadly, it has been hidden for many years. I reach out to you.

I’ve been following this event for months now. This article is a historically rich offering for the future. Can you imagine the children and grandchildren of Cherokee reading this article in five to 255 years to come while recounting “We are still here!”?! May the AniKituhwa continue to participate in the LNYDPs and break scones among the British and the world!