Joanne Prince, Rainmaker Gallery

Project Partner, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

Rainmaker Gallery is a partner on the ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ project. We recently had the honour of inviting the first BtS artist-in-residence, Marla Allison (Laguna Pueblo), hosting the first BtS symposium ‘Indigenous Art in Britain’ and presenting the first BtS exhibition ‘Marla Allison: painter from the desert’, 6 June – 11 August 2018.

The Rainmaker story began back in 1991, on a leafy street in south Manchester where I opened my first gallery. Since then I have been exhibiting Native art in the UK almost continuously. Curiously, the question visitors ask most often, is not about Native art or artists. It is “How did you get into this?” The more important question, however, is not how, but why. What was the motivation to do something so specialised?

In the 1980s, I was working at the Commonwealth Institute in London where I regularly came into contact with educators seeking material for teaching about “red Indians”. It seemed that most teachers were intent on instilling their own childhood fantasies in yet another generation. I became aware of the lack of real information about Native American and First Nations peoples. Such an information vacuum endlessly generates media stereotypes and simplistic ideas. Next to nothing existed here to challenge those reductive notions. As no one else seemed to have noticed, or no one cared, I decided to try to do something about it myself. Realising that people are deeply attached to their childhood fantasies, I found that the best way to expand their ideas and perceptions was to seduce them with beauty. The beauty of Native American art.

A platform was needed for Native art. A space where Native artists could express themselves as unique and contemporary individuals from diverse Indigenous cultures. At the fearless age of 26, I quit my job, rented a space and launched Rainmaker.

That first incarnation lasted for ten years. Initially the gallery focussed on art from the Pacific Northwest Coast. As I became more familiar with the work of individual artists, the vast scope of contemporary Native art gradually began to dawn on me. This was refreshing, exciting, and so much more interesting than the tired stereotypes of Hollywood Indians.

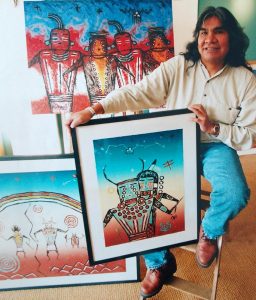

Cultural exchange is an important part of what we do at Rainmaker. In 1993, I travelled to New Mexico for the Santa Fe Indian Market where I was introduced to the late Hopi and Choctaw artist Dan Lomahaftewa. He shook my hand, looked me in the eye and said “I want to come to England. Can you help?” Until that moment I had never considered that any Indigenous artists would actually want to visit Britain, especially not sunny Manchester. Dan travelled to England the following summer for his first UK solo show. It was such a positive experience that he came back the very next year.

In the mid-nineties, Navajo artist Tony Abeyta invited me to direct his gallery in Taos, New Mexico. This was a pivotal experience and a truly exciting time for me. I lived with Tony and his then wife, fashion designer Patricia Michaels (Taos Pueblo) and their young family. I became immersed in the Native art world. Running two galleries on two continents sounds crazy to me now but back then I didn’t even question it.

Since relocating to Bristol we have staged at least seventeen specific exhibitions and hosted more than twenty Native artists and their families. For some artists it may be the first time they have travelled outside of America and it is a real adventure for them. I love being instrumental in that experience. Tony Abeyta was the first artist to come to Bristol for an exhibition, followed by Marcus Amerman, Edgar Heap of Birds, America Meredith, Sarah Sense, Chris Pappan, Debra Yepa-Pappan, Nocona Burgess, Cara Romero, Diego Romero and many more. Last year’s artist-in-residence Yatika Starr Fields was the first Native artist to participate in UPFEST, Europe’s largest street art and graffiti festival which happens here in Bristol every year. His mural remains as a lasting legacy of his visit.

Running a “commercial” gallery places many constraints on what is possible and viable. Crucially, I have to ask: will the work sell? Is the price point too high? Not everything we show needs to be commercially viable but much of it does. In 27 years without funding, every show has been a leap of faith. For those of you who think that opening a gallery sounds like a great career move, know this. Someone once said to me. “If you open a gallery you can make a small fortune, out of a large one.” Without a fortune large or small I did it anyway and whilst I have never made much of a living, I have made an incredible life. I feel truly blessed to work with amazing artists and to be surrounded by beautiful art.

Twenty seven years on from my initial idea, what is my purpose now?

I am still working to change perceptions. Having placed seven contemporary Native artworks into museum collections in the last three years, I am on a mission to create a paradigm shift in museums. I want museums to question why they have Native American collections and consider what message the displays give. Do they challenge popular misconceptions? Do they communicate an Indigenous perspective or are they colonial, historical and stereotypical? I challenge museums with indigenous collections to aim for a minimum of 50% contemporary content on display. This is important because museums reach a much larger audience than a commercial gallery and their teachings carry great weight in the minds of the public. Therefore, they can play an essential role in ensuring that Indigenous people are not forever seen as relics of the past but as essential members of, and contributors to, contemporary society.

Driven by the Native community, there is already a shift happening in museums in Canada and the USA. It also needs to happen here in the UK but, with no Native North American community to speak of, this change is inevitably slower. As curators, we must remember that our role is to illuminate not to dictate and crucially the narrative must be written by Native artists and communities. In the words of artist and jeweller Pat Pruitt (Laguna Pueblo – Chiricahua Apache):

“Native Artists will control that narrative. The narrative is NOT traditional vs. contemporary, that narrative is inclusive of all forms of Native Art, traditional, contemporary, and all forms in between.”

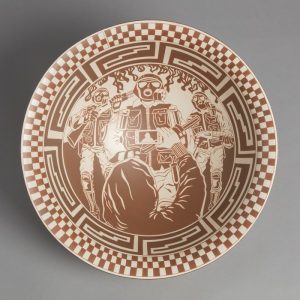

This paradigm shift can happen in the UK. Curators at Museums such as the American Museum in Britain and The Bristol Museum and Art Gallery are keen to add more contemporary Native art to their collections. Bristol Museum have already acquired several pieces from our recent exhibitions and last year commissioned an incredible pot from ceramic artist Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo). This was special because Diego is a major artist and the pot is both political and contemporary in design. However, I understand that when the Friends of the Art Gallery were approached for funding for the Diego Romero work, they decided that it did not qualify as art.

The hard truth is that if you are a European artist then Native subject matter definitely is art. In March this year I was shocked to see an image of a Hopi Squash Kachina on the front of The Guardian newspaper. It was a photograph of the Anthea Hamilton exhibition at Tate Britain. Nowhere in the article or on the Tate website was the true nature of this figure acknowledged. A token reference was later added in response to pressure from Native artists. This kind of misappropriation is particularly frustrating when Native artists themselves are seldom given such high profile opportunities here.

In her piece ‘The Last Indian Market’ fine art photographer Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) re-stages Leonard Da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’, placing Native American artists at the centre of the mainstream art establishment, effectively saying, “We deserve & demand a place at the table.”

It is my hope that in some way Rainmaker Gallery is raising the profile of contemporary Native art and artists here in the UK. I am delighted that the story of Rainmaker Gallery and all our Indigenous visitors will be included in the ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ research project, quite literally putting Native artists on the map.