Professor David Stirrup (University of Kent)

Principal Investigator, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

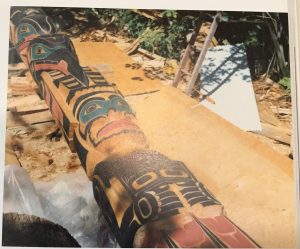

In early 2018, my co-Investigator Jacqueline Fear-Segal (University of East Anglia) and I were on a fact-finding mission to Salford, touring the city with councillor Stephen Coen, when he suggested we pause at a council warehouse. Opening the door we were greeted with a typical warehouse scene. However, the moving of several large water containers revealed something far less typical: prone, the form of a substantial totem pole, clearly Kwakwaka’wakw in its forms and lines. We knew about the pole, but not its whereabouts. After much consultation with representatives of Salford City Council, Fortis Construction, and contemporary Namgis carvers Kevin Cranmer and Bruce Alfred, we are excited to announce that Salford’s totem pole is to be restored, resited, and rededicated where it once stood—on the banks of the Manchester Ship Canal. Kevin, nephew of Doug Cranmer, the original carver, has told us: “It is said that totem poles are the footsteps of our ancestors; the art form itself is the aesthetic or visual expression of who you are and where you descend from. The ability to create this art affords you the opportunity not only to express an ancient history, but also to be an ambassador for your people.” In the returning of the pole to a prominent site in Salford, that ancestral presence in this distant land will once again become visible.

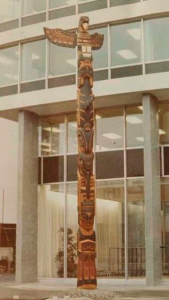

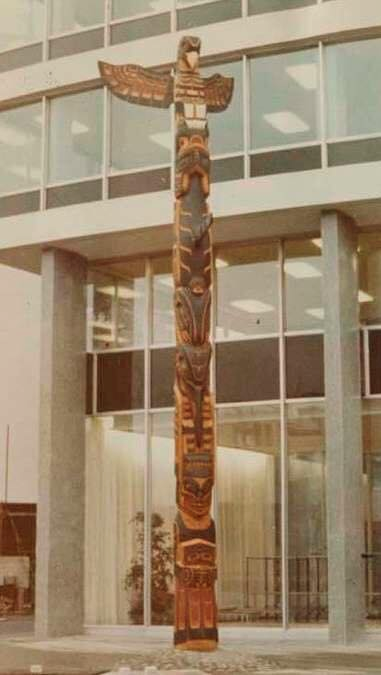

In the late 1960s, Robert Stoker, Chairman of the shipping firm Manchester Liners decided to mark the longstanding history of trade between Manchester and Vancouver by commissioning Namgis carver Chief Pal’nakwalagalis Wakas Doug Cranmer to carve a totem pole. The pole was to be situated in front of the newly constructed Manchester Liners House (later renamed Furness House), adjacent to Salford Dock No.8, just a stone’s throw from the canal that facilitated that company’s success. Cementing its relationship to Canada, the site was formally opened on December 12th 1969 by Charles Ritchie, then High Commissioner for Canada. In 2005/6, having fallen into disrepair, the pole was removed from the site—literally and sadly chainsawed at the base—and packed off into storage, in some accounts in Kent, in others Ipswich.

Northwest Coast art specialist Jennifer Kramer testifies to its significance, writing in 2013 that “This totem pole is significant because it is one of only a handful of totem poles that originated as commissions and were carved explicitly to be displayed in England, i.e. it did not arrive in England after being collected in a native village destined for a British museum.” Furthermore, Jago Cooper, curator of the Americas collections at the British Museum, notes “this object is of major cultural significance. Not only does the pole have an inherent and unassailable role to play within Kwakwaka’wakw cultural heritage and community identity but as one of the few well preserved house posts outside of mainland North America it acts as a vital means of communication of cultural plurality and different ways of life to a wider public.” (both in email correspondence with Stephen Coen).

Before its removal, the pole was an interesting choice of dedication to that Manchester-Canada relationship, testament perhaps to the ongoing fascination of the British with northwest coast art, and certainly to the ways in which certain iconic art forms such as the totem pole have become synonymous not only with Indigenous art forms but even with Canada itself. Alongside the canoe and the maple leaf, the former also an Indigenous form, few signs signify Canada so immediately.

Such signification, often appropriated and capitalized on by Canadian institutions, has tended to elide Indigenous cultures with the Canadian state, of course, overshadowing Indigenous sovereignty and somewhat erasing Indigenous histories. In the spirit of the original commission, however, which ultimately sought out a contemporary Indigenous maker with a brand new commission, this rededication will celebrate the pole’s legacy in forging new connections between Salford and the Namgis community, and particularly between the city and the Cranmer family.

As a project, we are committed to those connections and it has been absolutely vital to us—as it has been to Salford’s representatives—that relocation of the pole could only be carried out with the permission, cooperation, and involvement of the Cranmer family, and that it should provide an opportunity to foreground the voices and stories of contemporary Namgis. To that end, rather than my dedicating the remainder of this blogpost to further explanation of the pole and its significance to Salford, I’d like to hand over to Kevin Cranmer, one of the two carvers who will travel to Salford over the coming months to begin the work of restoration. Kevin very generously answered a number of questions I sent him via email. I present those questions and answers here:

How did you first learn about the “Salford” totem pole? What did you think when you heard about it?

I first heard about the pole around 2010 after receiving a phone call from Steve Coen. I was pleasantly surprised to hear about this pole. The only one that I knew of that stood in England was the pole that our great uncle Mungo Martin carved for Windsor Great Park in London.

What does it mean to you personally, to your family, and (if it’s at all possible to answer this – don’t worry if not) to the Namgis community more broadly, that this pole is over in the UK?

For me, the pole reaffirms what our family and our community in Alert Bay already knew. Doug’s artistic endeavours are well documented, and he carried the cultural mantle and chiefly duties passed to him from his father, Chief Dan Cranmer. It is said that totem poles are the footsteps of our ancestors; the art form itself is the aesthetic or visual expression of who you are and where you descend from. The ability to create this art affords you the opportunity not only to express an ancient history, but also be an ambassador for your people.

Had you heard of Salford before you were contacted about the pole?

I had definitely heard of Manchester before as my godson Edgar is a great fan of a certain football club from that city. I won’t mention the name of the club, but suffice to say they’re team color is Red—hehe—it was only after Steve had first contacted me that I became aware of the district of Salford.

What did you think of Salford / how did you enjoy your visit last time you were over in 2011?

I thought the city was great… the hospitality, the history… the football club… the quays… lots to see and do while there working on the pole.

There are, of course, other totem poles in Britain carved by members of your community. Is there a difference in your mind between the fact that this pole is in Salford as opposed to London? Does it have a different symbolic significance?

I don’t think there is really any difference between the two poles aside from dimensions and the crests portrayed on each. Both carry equal weight in a cultural sense, monuments to the history and strength of the Kwakwaka’wakw people.

Could you tell us a little bit about traditional totem poles? Why they are carved, who carves them, how one learns to carve? Where are they usually situated? What sorts of tools are used?

There are different types of poles, family crest poles, memorial poles, house entrance poles. For example, when our family potlatched this past November, I was afforded the opportunity to fulfill a longstanding desire to honor my late father by carving a pole in his memory. The crests portrayed on the pole pertained to the history of our late grandfather’s position—Chief Pal Nakwala Wakas, Chief Dan Cranmer. If there are carvers in the family they are usually the ones who create these poles, if not the Chief of the family will ask a carver close to the family to do so. The process of learning to carve is usually an informal one. For me it was a matter of asking our late Uncle and Chief Tony Hunt. From him I began to learn not only the physical skills of carving but the cultural knowledge and history of what was being created.

What sort of pole is the Salford pole? Are you able to tell us what story it depicts?

Although I never got the opportunity to ask Uncle Doug what the crests on the pole represented to him, from what I can see the figure on the bottom represents a chief, as he his holding a Tlakwa-or copper, which represents the wealth, standing, and history of a chief’s position. The Maxinukw—or Killer Whale—is a crest of the Namgis tribe. The Raven is one of the crests brought down by the matriarch of our grandmother’s Hunt family, that was my great, great, great, great grandmother Anisalaga, Mary Ebbetts, a Tlingit Noblewoman from the “Drift Ashore” house in Tongass Alaska. The Eagle or Thunderbird is another crest of the Namgis.

Could you tell us a little about how you plan to restore it, and how you feel about it being raised again in Salford?

The restoration will entail adding some new timber at the bottom to replace the timber that was cut off, and the repainting of the pole. It’s great the pole will stand again in Salford to continue to portray the history of our people.

Are you aware of any of the other stories in Salford about Indigenous North American visitors to the city? The Lakota performers who lived there for 5 months in the 1880s, for instance, or the Ojibwe missionaries who traveled through in the 1840s?

After first being contacted by Steve he made available the history of the other Indigenous visitors to Salford

Looking forwards, what would you like to see happen in terms of things like education and public engagement around the pole. Are there connections between your community and the people of Salford that you would like to see developed?

I think anytime we endeavour to learn more about one another’s history and cultures the more appreciation we will have for each other. In regards to all the tribes on the northwest coast, Salish, Nuu Chaah Nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw, Heiltsuk, Haida, Tsimshian, Tlingit… all are different and distinct in terms of their art forms, language, and cultural practices. The one thread that ties them all together is each one of their respective origin stories places them in their respective territories going back at least 10,000 years; as a matter of fact in Heiltsuk territory on Triquet island there was a village recently unearthed that is carbon dated going back at least 14,000 years ago. Anytime we are afforded the opportunity to share of ourselves and educate on our history we are tasked to do so by our forebears who lived between the years of 1884 and 1951. It was during this time the government of Canada forbid by law a way of life that existed since the time of our beginning.

We should note that this is not the first time an attempt has been made to resite the pole. In 2013, after failing to secure commitment from any of the quayside properties, the pole was briefly slated to be moved to the town of Swinton. Partial restoration took place in 2012, and the totem pole even had a brief sojourn in Amsterdam where it was put on display before returning to storage in Ordsall. That move fell through, however, and in a sense it is good that it did. Although it has meant several more years in hiding, there is now the opportunity for the pole to be restored to its original vantage point—the site it was made for—and to the people of Salford to whom it was gifted by Furness Withy.

We anticipate that Kevin, Bruce Alfred, and Doug’s brother Bill Cranmer will travel to Salford in August 2018 to look over the pole and meet with the developers to discuss the process its restoration and rededication will take. Representatives of Fortis Construction, Salford City Council, and the Universities of Kent and East Anglia, meanwhile, are signing a memorandum of understanding by way of committing to their various roles in the project. ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ Research Associate Jack Davy is discussing possible links with Manchester Museum, who have expressed interest in the pole in the past, and we are of course hoping to talk to other Salford- and Manchester-based institutions who may be interested in collaborating on educational and cultural projects around the pole. In addition to Fortis themselves, the Canada-UK Foundation have contributed funding to facilitate both the carvers’ work and education and outreach in the city. We will also be working closely with the carvers and other members of the Namgis community to develop curriculum materials that will be made freely available to schools in the area.

If you’re interested in learning more about this project, please do not hesitate to contact us, and you can also follow developments via the Salford Totem Pole Facebook page.

Watch this space!

Thanks Stephen – included now!

put the link in to the Salford Totem Pole Facebook page 🙂