Simon Black –

Working with people often involves bumping into ‘counter-intuitive truths’ (Seddon, 2003): ideas that contradict everything which we have been taught about managing people.

Leaders therefore need to think seriously about the people they are leading and their needs (i.e to enable those people to get on with the work) far more than thinking about the ‘principles of good leadership’. In other words, think about ‘followers’ more than yourself as ‘leader’.

In conservation, this allows us to avoid problems of working in remote sites (often in close proximity), having multicultural (or at least cross-cultural) teams, working in second languages (or with translation), having multi-disciplinary teams or mixes of unskilled and technical workers, and so on. Here are some of the realities and things to watch out for:

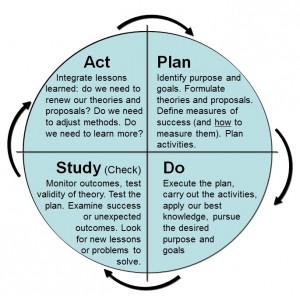

• Don’t ‘do it to people’: understand the system of work first – how work should be purposeful and how the flow of work (the order of tasks) can be made helpful

• Don’t chase things that don’t

• Don’t chase things that don’t

exist (like supposed ‘trends’ in data) or arbitrary targets

• Build knowledge, not opinion

•  Don’t rely on top down change; take a lead yourself and start small if necessary.

Don’t rely on top down change; take a lead yourself and start small if necessary.

• Teamwork is about Purpose, Goals & Process more than about Behaviour. A conflict between people may not be a personality clash but actually be about work organisation.

• Decision-making can involve people in many different ways. Participation and input from others will only help if they have insight and useful knowledge. It will also be really unhelpful if knowledgeable and insightful people in the team (or local community) are ignored.

• Change can be quick & painless at the right point of intervention (especially if you don’t ‘do it’ to people)

• Doing things that are ‘nice’ to people (appraisals, recognition, involvement), might not be nice for those people – especially if the obvious problems of work are not addressed.

Reading:

Beckhard, R. (1972) Optimizing Team Building Effort, J. Contemporary Business. 1:3, pp.23-32

Seddon, J. (2003). Freedom from Command and Control. Buckingham: Vanguard Press.