Simon Black –

Does conservation have the capacity to learn new ways of designing, testing and improving its interventions and impact? Good disciplines of management can be learned from other sectors, but still need to be applied, whether in the field, in zoos, and in collaborations with scientific institutions, governments and communities. The conservation sector is blessed with a motivated workforce – people who are committed to the recovery and survival of species and ecosystems and we need to make better use of their motivations.

Impact will not be amplified just through our best efforts which, whilst worthy, will essentially involve pushing water uphill (Deming, 1994). Rather we need to ‘work smarter’ by finding a better way to protect, recover and restore. This is not a far-fetched expectation, shown by examples of dramatic turnarounds with species like the Mauritius Kestrel and Echo Parakeet. It is a question of learning.

Conservation needs to apply new methods of problem identification, decision making, planning, monitoring and review, even in situations where we already have a sound understanding of conservation science of the species? I am always surprised by the frequency of projects that, despite available expertise and resource, are hampered either by people rigidly sticking to outdated plans of action, or by being allowed to drift off course due to the pursuit of ill-conceived goals. These are symptoms of a hesitant or uninformed management approach. Science cannot provide the answers to these problems (Clark and Reading, 1994).

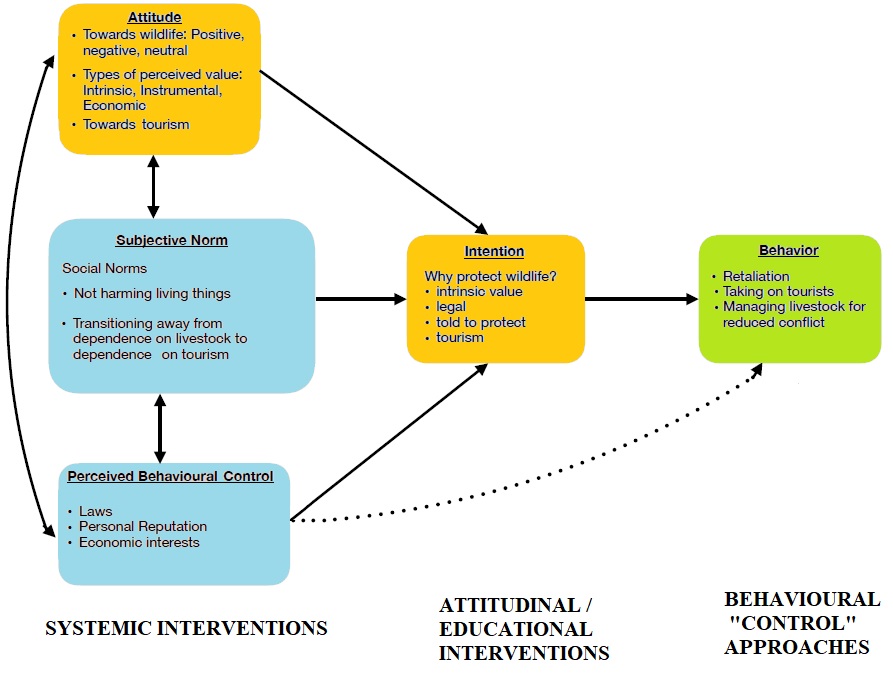

Conservation practitioners also need to learn how to grapple with scientific uncertainty, building arguments for the recovery of species in situations of scant information. Decisions of critical importance (such as how to save the last few individuals) can rely on little more than hunches, best guesses or deep assumptions; an approach which flies in the face of scientific expectations for decision-making based on hard evidence (Game et al., 2013). A vast proportion of thorny conservation problems are rooted in issues around people (either the ones generating the threat or the ones implementing the action) rather than biology. In the face of these demands only now are we beginning to realise that the old ways of managing conservation can be radically improved through skills which enhance thought, courage and emotional insight alongside better collaboration and creativity (Black and Copsey, 2014).

Aside from practitioners needing to acquire management skills, there is a second side to this; the humility to lead effectively. A conservation professional that is prepared to admit “I don’t know” is ready to pursue the right knowledge. The project manager who is prepared to admit “it is not working” will be ready to experiment with new solutions. The leader who is prepared to ask “what can we learn?” when someone has made a mistake will enable even the most experienced team to gain new insights into their work. This is a new horizon for many conservation professionals and it is not on the curriculum of a biological sciences degree. How much are we, as conservation managers, prepared to change the way we think?

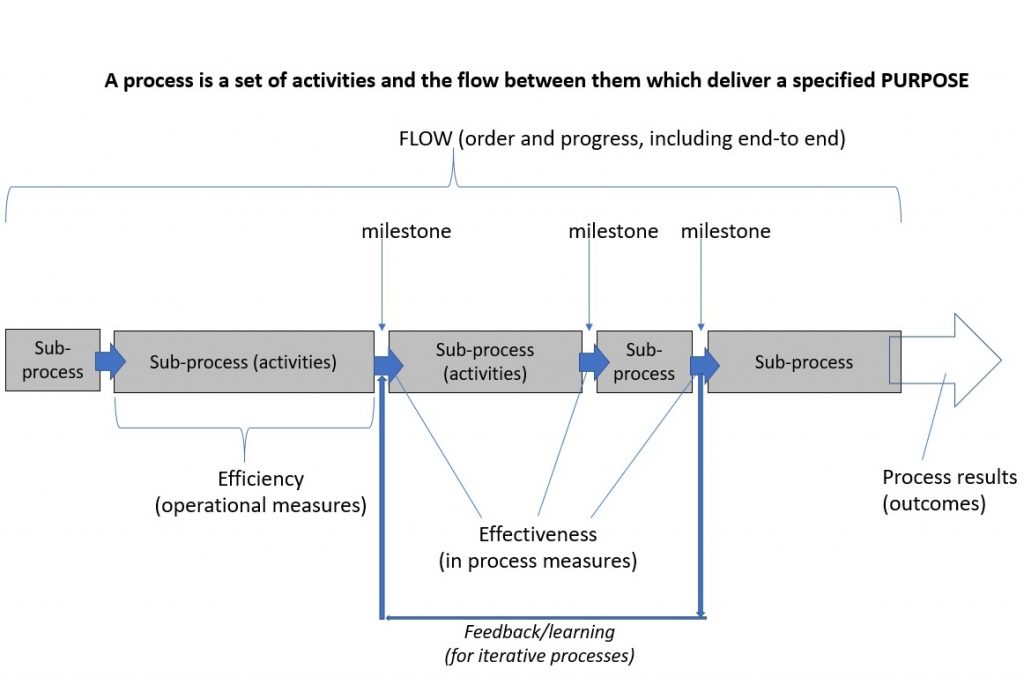

Fortunately we can call on nearly 100 years of sound management theory and practice, tested and validated through scientific study of psychology, statistics, experimental design, human behaviour and organisational theory. Good conservation management practice; working with species, people, resources, logistics, problems and policies requires a both a disciplined and passionate approach – an appreciation of the importance of long-term vision of what we need to achieve, alongside an understanding of the practical realities required to set meaningful short-term goals (Black, Groombridge & Jones, 2013).

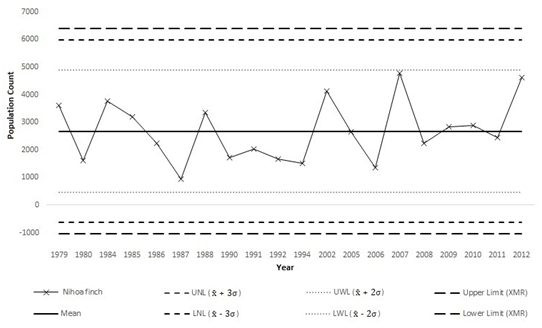

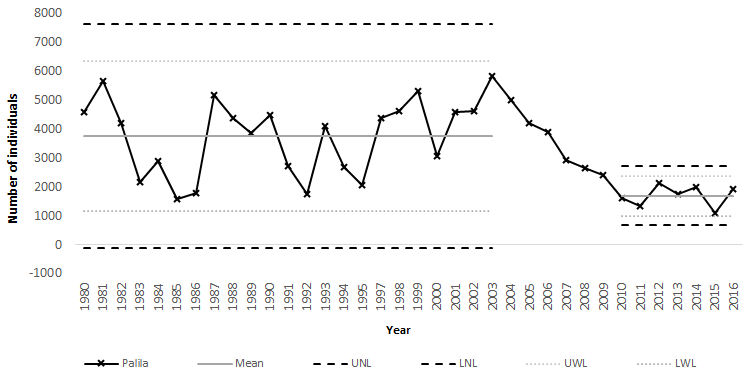

Many aspects of this ‘better way’ of managing (Deming 1994) are reflected the basics of effective conservation; knowing the species (morphology, behaviour, ecology nutrition, reproduction and its natural history) and understanding the threats, followed by a pursuit of ever-improving knowledge (husbandry, enclosure requirements, health management), usually alongside practical interventions (intensive management, captive breeding, community engagement). Often the tangible gains in recovering species are made through incremental improvements in knowledge and these changes start with anecdotal evidence of what works and what doesn’t. Over time, with good data management and systematic project design (data monitoring, planning and method development) the accumulation of anecdotes becomes data of scientific value. Scientific understanding thereafter enables wider questions to be explored and better understanding of species, communities and whole ecosystem recovery. There are many examples where a blossoming of scientific knowledge has run in parallel with concrete progress on the ground (Young et al., 2014).

It is an exciting time to be a conservation professional and an important time for zoos and field projects to adapt, learn and accelerate improvement: a better way for conserving species and ecosystems.

Reading

Black S.A. (2014) Can we engineer an exponential growth in conservation impact? Solitaire 25: 3-5. Durrell Conservation Academy, Jersey. ISSN 2053-1087. http://www.durrell.org/network/resources/solitaire/

Black S.A. and Copsey, J.A. (2014) Purpose, Process, Knowledge, and Dignity in Interdisciplinary Projects. Conservation Biology, 28 (5): 1139-1141.

Black, S. A., Groombridge, J. J. and Jones C. G. (2013) Using better management thinking to improve conservation effectiveness. ISRN Biodiversity http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/784701.

Clark, T.W., Reading R.P. (1994) A professional perspective: improving problem solving, communication and effectiveness. p351–369 in T.W. Clark, R.P. Reading, A.L Clarke, eds. Endangered species recovery: finding the lessons, improving the process. Island Press, Washington, D.C.

Deming,W. E. 1994. The new economics for industry, government, education. 2nd edition. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study, Cambridge.

Game, E.T., Meijaard, E., Sheil, D., McDonald-Madden, E. (2013). Conservation in a wicked complex world; challenges and solutions. Conservation Letters 7 (3): 271-277

Young, R.P., Hudson, M.A., Terry, A.M.R., Jones, C.G., Lewis, R.E., Tatayah, V., Zuel, N., Butchart, S.H.M. (2014) Accounting for conservation: Using the IUCN Red List Index to evaluate the impact of a conservation organization. Biological Conservation 180:84-96