Simon Black –

Monitoring and evaluation is a common headache for conservation leaders. how do they evaluate the impact of a programme, intervention, or project? One of the big problems is that conservation professionals cannot attribute ’cause and effect’ to their interventions, so assume that they cannot suggest or claim that improvements have been ’caused’ by their intervention.

This false modesty is a problem, because it encourage even more spurious claims in its place – like recovery of species on a global scale, or a discussion of increased population counts when other factors may be involved. Few can claim (although some can truly claim with certainty) that without intervention an extinction would have occurred.

We end up in a spiral of despair – will anything we do make a difference?

A new approach to leadership is required. This includes seeking ways of understanding the impact of conservation work on the systems of concern. this means understanding the status of the species and ecosystems involved. That understanding will never be complete – there will be many gaps and unknowns.

For example, the status of a species will not be known merely from its population size. There are many demographic, genetic, health and range-related factors well as an understanding of threats. However often there is no such data available nor the resources to measure and monitor these factors. In some instances we might not even know the baseline or historic situation for the species or ecosystem.

To improve our understanding in these situations the first thing that needs to be done is to start looking at the available data over time. Instead of a snapshot look at the dynamics of the data as a surrogate measure of the status of the species.

In this cas

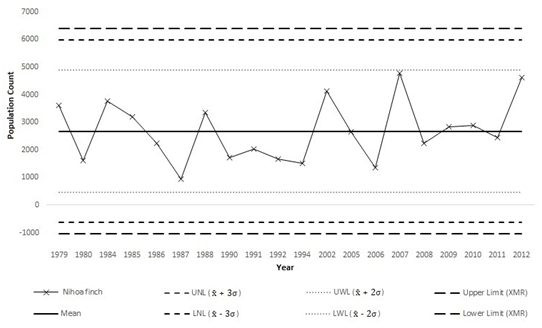

In this case a population of birds remains stable (Pungaliya et al 2018)

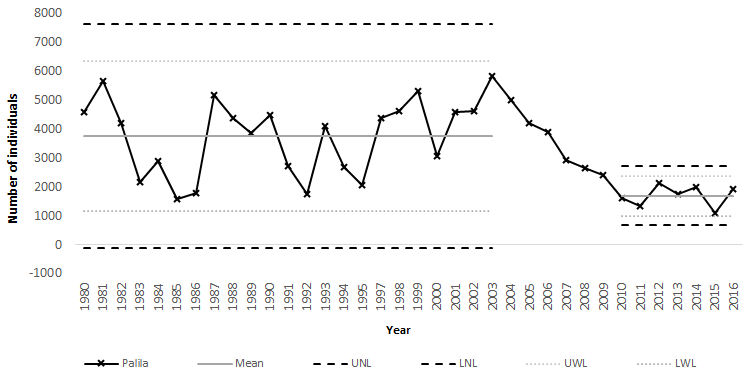

e a bird population has declined in size, but has become more stable and less prone to fluctuations in size (Pungaliya and Black 2017).

If we look at a threat, such as deaths of manatees in human-built lock and canal systems, we can start to see if the situation is improving, or not. In this case, new control systems on lock has reduced the number of deaths (Black and Leslie 2018)

Statistically derived limits (defined by the data itself and NOT an ‘expert view’) enable us to see whether actual changes can (i) be identified and (ii) be attributed to any actions taken in terms of conservation effort.

We can start to consider management conservation for real improvements.

Further reading:

Black SA and Leslie SC (2018) Understanding impacts of mitigation in waterway control systems on manatee deaths in Florida. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol 3 (5), 386‒390. https://medcraveonline.com/IJAWB/IJAWB-03-00124.pdf

Pungaliya AV, Leslie SC, Black SA. (2018) Why stable populations of conserved bird species may still be considered vulnerable: the nihoa finch (telespiza ultima) as a case study. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2018;3(1):41‒43. https://medcraveonline.com/IJAWB/IJAWB-03-00050

Pungaliya AV, Black SA. (2017) Insights into the recovery if the palila (Loxioides bailleui) on hawaii through use of systems behavior charts. Int J Avian & Wildlife Biol. 2017;2(1):4‒5. https://medcraveonline.com/IJAWB/IJAWB-02-00007