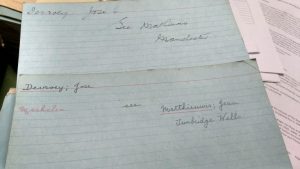

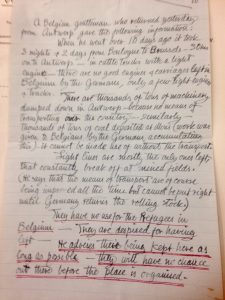

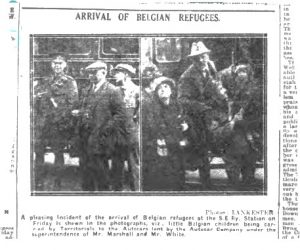

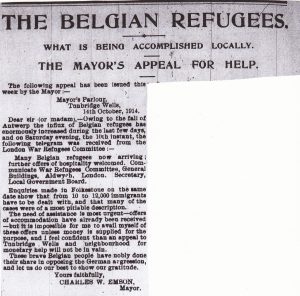

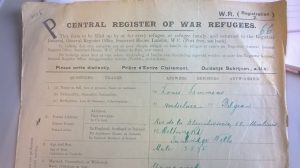

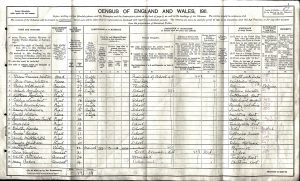

The Germans had demanded the right of passage through neutral Belgium to attack France. King Albert retorted ‘Belgium is a nation, not a road’. Belgians refused to stand aside as Germans marched through their country and resistance to their advance disrupted the German time-table for advancing into France. However Belgian resistance came at a cost and 200,000 Belgian refugees fled to the UK in 1914 and by 1917 that number had grown to around 250,000, amongst them many Belgian wounded soldiers. They arrived in England – most prominently at Folkestone – and after processing were dispatched on special trains to various towns and villages in Kent, one of those being Tunbridge Wells.

On 23rd October 1914 the Kent and Sussex Courier reported that in addition to the 23 wounded Belgian soldiers in the Tunbridge Wells General Hospital, ‘a number of other wounded men from this heroic little land are being tenderly cared for in various other Institutions’.

The Courier described the arrival of some patients. ‘On receipt of an intimation shortly before 11 o’clock on Friday night that a number of wounded Belgian soldiers were being sent in a special train to Tunbridge Wells, First Officer Hickmott at once got together eight men of the Tunbridge Wells detachment of the St John’s Ambulance Corps and proceeded to the [railway] station. The train was delayed, so the volunteers ‘had a tedious wait throughout the long cold night’. Eventually the train containing the 20 Belgians arrived. Two young ladies acted as interpreters and the wounded were taken to various hospitals by car. Their destinations included the Homeopathic Hospital, West Hall, Chilston Road, and the Kent Nursing Institution (Jerningham House) in Mount Sion.

Some of the Belgians had serious bullet or shrapnel wounds. According to the Courier report, ‘one had a bullet pass through his shoulder making two jagged holes in his overcoat’ and another ‘had one of his fingers taken off by shrapnel’. Others were worn out by prolonged fighting. One soldier at the Jerningham House hospital had pneumonia and was injured from falling into a trench. ‘The wounded men proudly show their torn clothing as trophies of battle honours’, the newspaper explained and they were reported to have claimed that they were being “treated like princes” and were ‘never more comfortable in their lives’. The Courier noted that ‘Belgian refugees who were staying at Wadhurst visited the … wounded men [who] greatly appreciated the opportunity of a few minutes chat with their compatriots’. If recovering soldiers went for a walk they were allegedly ‘lionised by admiring English women, several of whom have begged buttons from the soldiers’ tunics as souvenirs of the war’.

Many local hospitals received Belgian casualties including the Eye and Ear Hospital (which took men with eye injuries) the Homeopathic Hospital, and West Hall VAD Hospital. There were also soldiers at the Victoria Hall, Southborough and Bidborough Court. The journal of West Hall shows that some 66 wounded soldiers had passed through the hospital by 19th November 1914, with 35 wounded soldiers in Bidborough Court, and another 35 at the General Hospital.

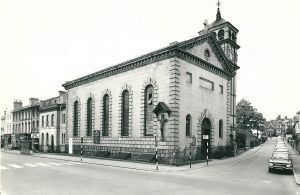

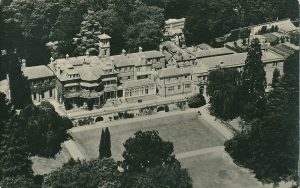

Bidborough Court 2017 (photograph © Anne Logan)

The Royal Victoria Hall, Southborough was turned into a hospital by the Southborough Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) for which Lady Salomons was the Honorary Commandant, while the Speldhurst VAD established the hospital at Bidborough Court. According to the Courier (6 November 1914), the patients received many visitors, including Belgian royalty and other notable ladies, who brought gifts of flowers and cigarettes. Well-wishers sent vehicles so that the wounded men could be taken for drives. It was reported that one of the Belgian soldiers, who spoke a little English, found out that his mother at Dover. Mother and son were reunited to ‘their mutual delight’. Although some patients were doing well, others were still suffering a good deal. The Courier (30 October 1914) reported that the patients were thankful ‘for all that is being done for them.’ The rooms at Bidborough Court were ‘large and airy and have been splendidly equipped by the Detachment, with the help of many friends who have kindly loaned the furniture, beds and bedding’. The property also had beautiful grounds for convalescents to take walks in.

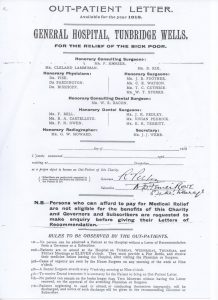

At the General Hospital, where 60 wounded English and Belgian soldiers were being looked after, the management had to hire a barber to shave the men. This was an item of considerable expense and could not be met from the ordinary hospital fund, so the Courier reported that a request was made for special, small subscriptions towards the cost.

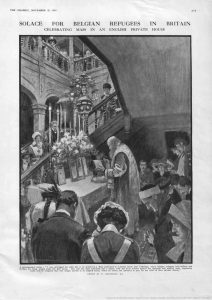

According to the First World War diaries of Lady Matthews, kept for the benefit of her children, in late 1914 hospitals were also being prepared in Rusthall, where some ladies had only just passed their St. John’s Ambulance examination. By August 1915 the Rusthall hospital was full, and had orders to supply 30 more beds. Lady Matthews described her visit to a private hospital where she saw ‘both Belgian and British soldiers in great comfort in a luxurious private house where the billiard room wing has been converted into wards’.

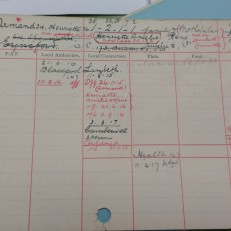

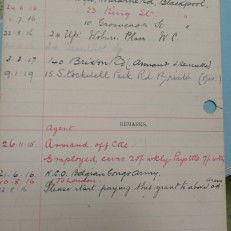

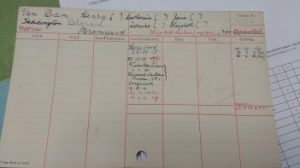

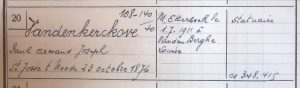

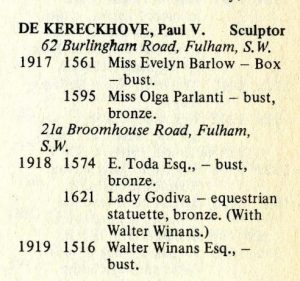

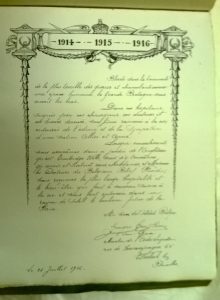

One of these wounded soldiers hospitalised in England was Sgt Georges Cantillon who was awarded the Order of the Chevaliers de Leopold II (equivalent of the British VC) for bravery. Although he was ‘wounded in the face and hand he nonetheless pursued the enemy, taking out the patrol leader’. Sgt Cantillon later played an important part in social activities of the Belgian community in Tunbridge Wells and at the Club Albert – the Social Club, running the tombola. Himself an artist, he donated a painting for the tombola on the Belgian King’s birthday in 1915. In mid-1917 he probably left England for France.

Cantillon’s page in the Scott Album (photograph © Alison MacKenzie)

By 1915 the wounded Belgian soldiers had mostly recovered and their places in the VAD hospitals were taken by British casualties. Some soldiers returned to the army while those who were not well enough to fight stayed on, and were employed, in Tunbridge Wells or went to work elsewhere, for example in munitions factories.

Sources:

Kent and Sussex Courier 1914

HetArchief 1915

The Times 1914

International Encyclopaedia of First World War

Barbara Tuchman (1962) August 1914.