As we translate works from Japan into an understandable format for Kent, and vice versa, we begin to see patterns emerging.

Airborne

Rising up, carried by the wind, day and night, the balloon is a happy nomad, travelling across the landscape, before it meets up with its free-floating companions.

Paper artist Chisato Tamabayashi’s pop-up book, Airborne, tells the story, without using words, of a hot air balloon floating across the countryside.

The simplicity of design made the book the perfect artwork to project the Museum of Imagined Kent’s message onto: whilst we imply the river depicted is the River Medway, it could equally be anywhere, either here in the UK or in Japan. Through the balloon crossing the river, we explore the idea of ‘translation’ as the moving from one place to another, and how translation can lead to change. In this way, Airborne helped to illustrate both the similarities between Kent and Japan, and also how meanings can get muddled – how can you trust a label telling you this book definitely represents the Kentish countryside?

London-based Tamabayashi is inspired by traditional Japanese art and craft. Her pop-up books have links to the craft of kirigami, a variation of origami, where the paper is cut as well as folded. Each page explores different techniques elements that, amongst others, pop up, fan out, and can be controlled using paper strips.

The balloon links the work perfectly to Mitsumasa Anno’s picturebook My Journey, where a red balloon is seen moving through the world, hovering over the countryside on every page. In both cases, their minimalistic representation of the countryside helps us to tie these books to Kent, and draw connections between the county and Japanese art and culture.

See more of Chisato Tamabayshi’s works here

Learn more about kirigami here

My Journey (旅の絵本)

‘I wandered from town to town, country to country and sometimes my journey was hard, but it is at just such times that the reward comes. When a man loses his way, he often finds himself – or some unlooked-for treasure’

Mitsumasa Anno’s picture book explores a journey through the English countryside across double page spreads of fields and towns, full of intricate details and hidden surprises.

Although, like Chisato Tamabayashi’s Airborne, we can’t know for sure that the pages depict the Kentish countryside, we see indications such as oast houses, traditional buildings used to dry hops that are thought to have originated in Kent, and medieval market towns that look remarkably similar to Canterbury!

A tiny red balloon, escaping a child’s hand and floating across the pages, links the work to others such as Tamabayashi’s in our Kentpan section, but it is by no means the only easter egg that catches the viewer’s eye. Across the pages artworks by the likes of Van Gogh and Seurat are recreated, and fairytale scenes are hidden in woodland clearings.

We see the issues of translation come through again here: although in most parts, we see clear signs that the landscapes and villages represented are English, there are parts mixed in which seem more like they come from mainland Europe, as personal experience and culture is added to the mix. In this way, we can link the work to Utagawa Toyoharu’s French Churches of Holland, where parts of Europe are jumbled and combined with elements of Japanese culture – translation is not always a perfect artform, but can sometimes add a whole new dimension to the mix.

Read more about My Journey here

Read more about Mitsumasa here

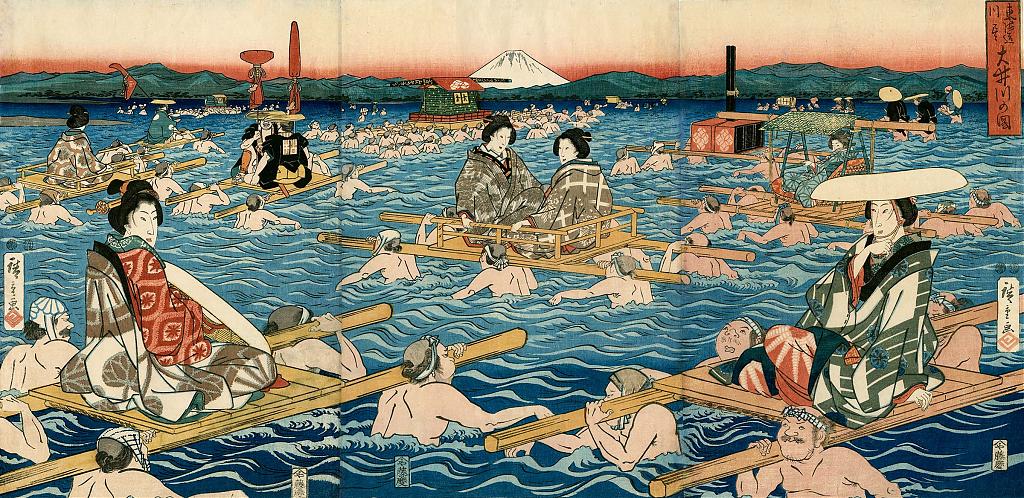

Oigawa River Crossing

‘Its waters gush with the speed and power of an arrow…If they lose their passenger, they lose their lives.’

Not much is known about this ukiyo-e woodblock print, date and artist unknown. However, we are aware of many similar artworks, leading us to date the artwork to the late 18th or early nineteenth century. Woodblock artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige (as featured in the exhibition with The Lobster) and Utagawa Kunisada have created similar works.

The Oigawa was a particularly dangerous river in what is now Shizuoka prefecture in Japan. Due to the challenging speed and direction of currents, you could pay for a skilled porter to carry you over the river. This continued from the 17th century until 1871, when ferries took over favour. The cheapest way to travel was for a porter to carry you, but you could pay more for a litter.

Ukiyo-e, or floating world prints, were woodblock prints that were particularly popular from the 16th to 19th centuries. Woodblock prints were a convenient way of mass-producing colourful artworks, and their subjects ranged from actors’ portraits to landscapes. The ‘floating world’ refers to the hedonistic lower-class districts of theatre and arts. Oigawa River Crossing is an example of shunga, which were erotic prints. These ranged from sexually explicit to implied eroticism, as in the case of this artwork, but clues can be spotted in the leering faces of the litter-carriers, and in the implications of the women wrapping their legs around the porters’ heads.

This print has lost most of its colour, likely due to being poorly conserved, and exposed to too much sunlight. This work would previously have been bright with colour, but now only the intricate patterns in blue on the women’s kimonos remain.

Although decidedly not depicting Kent, this piece illustrates the concept of translation, as discussed in the cases of Airborne by Chisto Tamabayashi and Mitsumasa Anno’s My Journey. Here, translation refers to the crossing of the river itself, just as the Museum of Imagined Kent bridges Kent and Japan, and shows how concepts often end up translated when displayed in the museum, ending up changed at the other end.

Learn more about ukiyo-e here