By Jessica Falkner, MA student, Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies

In the early hours of 24 August 1572, the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre began. It was a week-long massacre of Huguenots by Parisian Catholics believed to be instigated by Queen Catherine de Medici, mother to King Charles IX. This massacre led to similar massacres in cities throughout France. The total death toll is disputed among historians, with estimates varying between 2,000 – 10,000 in Paris alone. Our walking tour, led by Dr Rory Loughnane (Co-Director of the Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies) and Prof. Anne-Marie Miller-Blaise (Sorbonne III) gave a sense of the chaos of the massacre within Paris. It is not too hard to imagine that during the time of the massacre, Paris streets were crowded with buildings, with even the bridges containing numerous structures. On our tour on February 10th 2022, MEMS students were joined by students from Sorbonne III who were also learning about the history of Paris.

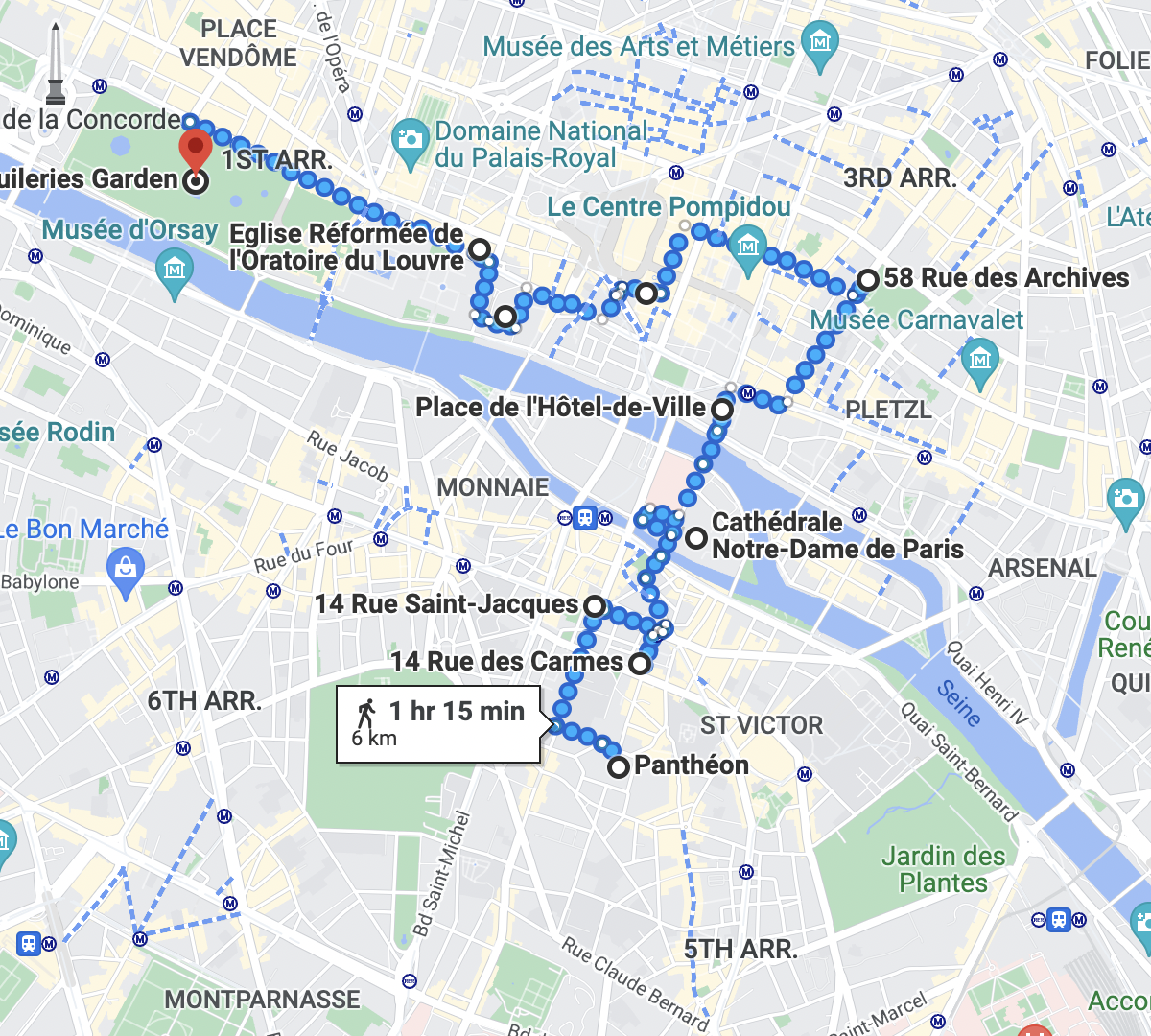

Our tour began outside the Panthéon which was not constructed yet at the time of the massacre. This area of the modern 5th arrondissement was the outer limits of Paris in 1572. It is situated near the Collège de France where Petrus Ramus was a leading professor of philosophy and a convert to Protestantism. As a result of his role at the Collège, Catholics feared that he, and others at the Collège, would lead a movement to convert others to Protestantism and therefore became a target during the massacre.

We walked from the Panthéon to Rue St. Jacques, where Ramus hid in a bookstore for three days before returning to his lodgings on 26 August. We followed Ramus to Collège de Presles, a secularized chapel at 14 Rue des Carmes, where Ramus was fatally stabbed. As we learned, it is possible that his fame across Europe increased because of his untimely death.

Leaving unfortunate Ramus, we went to Cathédrale Notre-Dame where the wedding ceremony of Henri Navarre, future King Henri IV of France, and Margaret of Valois was performed. The wedding was arranged as a method of peacekeeping between the Catholics and the Huguenots. However, Pope Gregory XIII would not grant a dispensation for the interfaith marriage so Henry and the other leading Huguenots who were there to celebrate the wedding were forced to remain on the square outside the cathedral while a proxy stood in for Henry. This, understandably, irritated the Huguenots.

Our next stop was Place de l’Hôtel de Ville, which was known as Place de Grève until early in the seventeenth century. It is in this inviting, lively square that we were reminded of the ever-changing nature of public spaces. Despite its pleasant appearance now, the square was the site of many particularly gruesome executions, including that of François Ravaillac. Ravaillac, a Catholic, assassinated King Henri IV by stabbing and was drawn and quartered in the square.

We moved on to the Hôtel de Guise, home of the Duke of Guise. The Duke of Guise was a leading Catholic and it was here that the plot to massacre the Huguenots was conceptualized. Because of the wedding of Henri and Margaret, many leading Huguenots were in Paris and Guise and others decided to take advantage of the chance to kill them. The first attempt was had when Gaspard II de Coligny, Admiral of France, a leading Huguenot, the day after the wedding, was shot. However, Coligny was only injured. In an attempt to smooth over the heightened tensions the shooting caused, Charles IX sent his doctor to treat Coligny. Unfortunately, Coligny’s shooting just caused the Catholics to fear retributions from the Huguenots.

On our way to the church where the plot came to a head, we passed a couple noteworthy places. First, we passed the spot where King Henri IV was assassinated by Ravaillac, now a busy street with nothing more than a simple sign to mark the important event. We also traveled down Rue de Rivoli, formerly known as Rue de Béthisy, to the spot where Coligny was brought for treatment after he was shot. Unfortunately, once the massacre started, Coligny was stabbed and thrown out a window.

We arrived at the Church of Saint Germain l’Auxerrois. It was at this church, located across from the Louvre Palace, that the signal was given for the beginning of the massacre, when its bell was rung in the early morning hours. It was from here that Catholics traveled to the Tuileries Palace, where many of the leading Huguenots were staying, to begin the massacre.

We ended the tour at the Église Réformée de France, the largest Protestant church in France, across the opposite street from the Louvre Palace than the Saint Germain. Here, there was a large statute of Coligny. While it was originally a royal chapel, it was given to the Protestants by Napoleon.

Overall, the walking tour was a great way to envision the history of Paris while also bringing new perspectives about how history has shaped modern spaces.