History of Medicine Undergraduate Essay Prize 2018

The forcible feeding of the suffragettes, although shocking in its practice, was a useful device to heighten public support for the fight for suffrage and gain recruits to their cause. Forcible feeding was used by the government on suffragette prisoners who were on hunger-strike as an alternative to realising these female prisoners early. After being adopted by the suffragette leadership and mobilised throughout the rank-and-file suffragettes, this weapon became highly effective for the suffragettes as it demonstrated both the brutality of the authorities, and the resilience of the women. When the reports of the first women who were forcibly fed were released into the public domain, there was an immediate public outcry. This indignation came not only from the W.S.P.U. themselves in their newspaper Votes for Women, but also within parliament and the national press, where terms such as ‘violence’, ‘torture’ and ‘violated bodies’ were used to intensify opposition to this procedure.

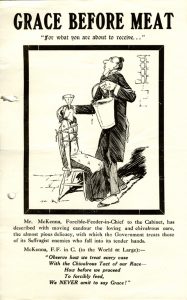

Images of suffragettes suffering in prisons, and depictions of them being forcibly fed were used to gain sympathy from the general public and increase public awareness for female suffrage. One of these propaganda posters was a pamphlet named ‘grace before meat’, which depicted a well-dressed caricature of Mr Mckenna who worked for the Home Office, brutally force-feeding a suffragette (figure 1). The message of this pamphlet was that a supposedly civilised country was committing barbaric acts on some of their female citizens, showing the conflict between those two ideals. The suffragettes also pushed for their propaganda material to reach as many members of the public as possible, as they urged readers to ‘pass this on to your friends’.[1] They attempted to harness the shocking nature of forcible feeding to gain the political advantage and publicise these posters to the widest audience possible. From their perspective, the harsh treatment they faced at the hands of the government was especially insulting considering they were being forced to conform to a government in which they had no part electing. Consequently, they took ownership of force-feeding, minimising the role the government had in publicising the procedure, and thus allowing themselves the platform to manipulate the reporting of it to the public.

The official narrative of forcible feeding which emerged from the government stated that forcible feeding was a necessity because of the antagonising actions of the suffragettes. In effect, the government claimed that they were protecting the suffragettes and providing treatment in prison, however, they actually abused the process of force-feeding, and instead used it to punish the suffragettes who were nationally humiliating the government. The government aimed to purposefully degrade the suffragettes by not cleaning out or changing the tubes used during the forcible feeding procedure between prisoners, making the process even more unsanitary. Rose Lamartine Yates, a suffragette, confirms this viewpoint as she publicly wrote that ‘the system consists of enforced degradation from beginning to end’.[2] This issue was also readily mocked by the government as was shown when Keir Hardie, the Labour leader, raised a question about force-feeding for discussion, and was met with roars of laughter from other MPs, showing how they trivialised the matter. The government remained largely out of touch on how this issue was influencing the public, as when six women were forcibly fed in October 1909 in Birmingham, twelve more women volunteered to go to prison to face forcible feeding almost immediately afterwards in Newcastle. This demonstrates how the government often did not judge public opinion accurately, and how they were, in some instances, counterproductive when launching their attack on the suffragettes. So, both the suffragettes and the government had the capability to use and manipulate forcible feeding for their own advantage, but it was the suffragettes who had the upper-hand in this instance, relegating the government into second place.

The original intention of the suffragettes’ hunger strike was to gain political prisoner status. It was only after the group saw the potential benefits from widescale implementation of the practice and how it could be manipulated, that it was developed further. Thus, the hunger strike was promptly transformed into a protest carried out by a mass of militant women. In her writing to the editor of The Times, Rose Lamartine Yates claims that the suffragettes ‘opened the eyes of humanity and forced elementary reforms on the prison authorities’, showing how the suffragettes had the opportunity to influence the public’s perception of them.[3] The idea of forcible feeding, which the suffragettes largely themselves propagated, was so shocking a procedure to much of the public because it challenged contemporary norms regarding conventional feminine behaviour. Therefore, one of the key strengths of hunger striking and force-feeding originated in the fact that it challenged the authority of the male-dominated medical profession and helped to develop a more modern notion of what it meant to be female.

With women suffering from the laceration of the throat, stomach damage, heart complaints as well as the potential of pneumonia if food entered the lungs, forcible feeding could be highly dangerous, and potentially fatal in inexperienced hands. A surgeon named Forbes Ross, stated in The Observer that he considered forcible feeding to be ‘an act of brutality beyond common endurance’.[4] Ross was actually not an avid supporter of the female suffrage movement, choosing to remain largely indifferent, but he still spoke out about the potential dangers proving that the risks of the procedure had the potential to overshadow the political nature of the events. Numerous individuals, including many suffragettes, and the Labour leader Keir Hardie, described the procedure as more akin to medial torture than medical care, showing how scarring the procedure was on the individuals, and how politics was able to broaden the debate on forcible feeding. Furthermore, suffragette May Billinghurst reported that ‘it was quite impossible to set the tube up the left nostril although [the doctor] tried with all his might…this caused me excruciating agony’.[5] This shows that the prison authorities were unnecessarily brutal when it came to administering force-feeding and were not concerned with the health and feelings of the individual women. Additionally, the Earl Russell, an MP, asked the government ‘why their treatment in prison is more severe than that usually awarded to political offenders’.[6] So, the government were imposing unnecessary amounts of suffering onto suffragette prisoners through force-feeding, and thus, in reality, transformed this medical procedure into a cruel punishment.

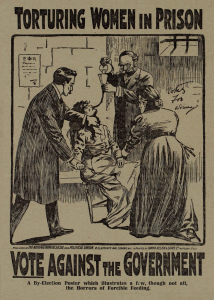

In a letter to a fellow suffragette, Lilian Lenton describes how she would ‘heave at the right moment’ to make herself sick after the withdrawal of the forcible feeding tube, showing how some of the suffragettes manipulated the authorities by making the conditions under which they were living in prison worse.[7] A poster published and distributed directly by the W.S.P.U. portrays a suffragette being brutally forcibly fed by the government, and the poster instructs the public to ‘vote against the government’, showing their attempt to mobilise the public through print (figure 2).[8] However, they were not always successful in this manipulation and they did not always receive positive attention, especially in the early days before the policy of force-feeding had been properly implemented. The Evening News reported negatively on this evident exploitation, and counter-argued that they should suffer the full proper punishment. So, the suffragettes were not unchallenged on the issue of forcible feeding and did receive some negative attention for their tactics. That being said, the procedure did have some deeper ramifications, as it prompted questions about the ethics of performing this seriously dangerous procedure on sane, unwilling participants. Prior to its use as a punishment for suffragettes on hunger strike, forcible feeding was predominantly used on patients in asylums. So, the forcible feeding of the suffragettes by the state gained significance as it raised deeper questions within society about the jurisdiction of the government, and it opened up a discussion about the role of ethics in medicine.

When advised that she should stop her hunger strike, May Billinghurst noted ‘how impossible that would be to me to throw away the only weapon left to me to fight for freedom’.[9] The suffragettes were aware of the power they possessed in using their bodies to fight for their freedom, and the right to vote, whilst also feeling limited in other ways by the actions of the government. The controversial nature of forcible feeding, and the nature of the relationship the government had with forcible feeding, was magnified by the conventional Edwardian characterisation of these women as vulnerable individuals, an idea that they themselves promoted to some extent. The suffragette Lilian Lenton states that ‘[the government had] resorted to force against the women, which is symbolic of a savage beating a female into submission’.[10] The brutality of forcible feeding eclipsed the original intentions of the suffrage movement and went on to influence the legacy of the suffragettes, and also opened up discussions about the capabilities and roles women could undertake within society. Through suffering forcible feeding and fighting towards getting the vote for women, these women were also working at breaking down barriers put in place because of their gender, and re-defining their roles as women within society. The suffragette stance on forcible feeding became significant as it allowed these women to take ownership of their own narrative and push back against the government to continue to pursue their fight for female suffrage. Forcible feeding transgressed deeper than just being a political tool used by both sides, and went on to mark one of the most complex and controversial aspects of the suffrage campaign. The suffragettes were given the ability to manipulate the government and the public with just their bodies, showing how they were able to harness the power of their physicality and use it to their advantage. Through their commentary on their experiences with forcible feeding, these women were able to gain some much-needed agency. The way in which these suffragettes took control of a situation in which they originally had very little and shaped the narrative of forcible feeding as a whole empowered and inspired so many women, and thus made forcible feeding one of the most significant aspects of the female suffrage campaign.

[1] Papers of Emily Wilding Davison- The Women’s Library, London- 7EWD.

[2] Articles and lectures by Rose Lamartine Yates-The Women’s Library, London- 7RLY/1.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Miller, ‘‘A prostitution of the profession’? Forcible feeding, prison doctors, suffrage and the British State, 1909-1914’, p. 243.

[5] Manuscript account by May Billinghurst- The Women’s Library- 7RMB/A/24.

[6] PRISON AND PRISONERS (4) OTHER: Suffragettes- The National Archives, London- HO 144/882/167074.

[7] Lilian Lenton to Nina Popplewell- The Women’s Library, London- 7POP/1.

[8] Manuscript account by May Billinghurst- The Women’s Library, London. [7RMB/A/24]

[9] Manuscript account by May Billinghurst- The Women’s Library, London- 7RMB/A/24.

[10] Lilian Lenton to Nina Popplewell- The Women’s Library, London- 7POP/1.

Bibliography

Brown, Alyson, ‘Conflicting Objectives: Suffragette Prisoners and Female Prison Staff in Edwardian England’, Women’s Studies, 31 (2002), 627-645.

Green, Barbara, Spectacular confessions: autobiography, performative activism, and the sites of suffrage 1905-1938 (London: Macmillan, 1997).

Geddes, J.F, ‘Culpable Complicity: the medical profession and the forcible feeding of suffragettes, 1909-1914’, Women’s History Review, 17 (2008), 79-94.

Miller, Ian, ‘Necessary Torture? Vivisection, Suffragette Force-Feeding, and Responses to Scientific Medicine in Britain c. 1870–1920’, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 64 (2009), 333-372.

Purvis, June, ‘The prison experiences of the suffragettes in Edwardian Britain’, Women’s History Review, 4(1995), 103-133.