“The tongue is mightier than the pen.”

– Sir Cecil Syers, head of the University of Kent Appeal Committee.

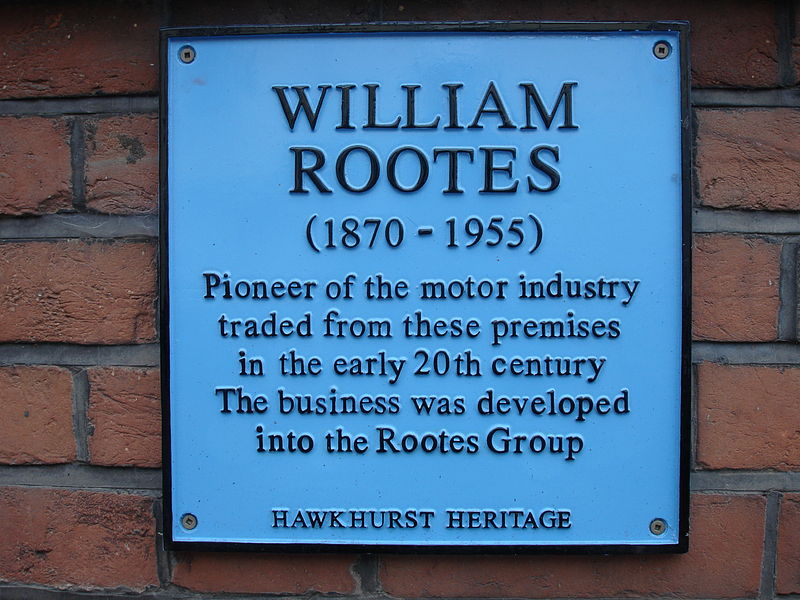

In September of 1962, Dr. Geoffrey Templeman, soon to be Kent’s first Vice-Chancellor, wrote to the Sponsors of a University in Kent describing his admiration of what he described as the ‘Rootes’ method of fundraising. Lord Rootes was a Coventry industrialist, whose efforts as Chairman of the promotion campaign for the new University of Warwick were credited with successfully fundraising £4 million.

Rootes had operated through using his personal and business connections, securing £150,000 from Jaguar alone. Templeman, concerned that Kent was ‘lagging behind’ the other new British universities, insisted that the University also capitalised upon these kinds of networks. This was one reason why the University decided not to use a professional fundraising company, believing that the Sponsors of the University could network to elicit money by themselves.

Another reason for abandoning the notion of using professional fundraisers was cost. Several companies solicited for the job, including John F Rich & Son, who had previously fundraised for Eton and other schools; and Hooker, Craigmyle & Co., Britain’s first fundraising consultancy. They were seen to be overpricing their services :Dr John Haynes, County Education Officer and Secretary of the Sponsors, described the “£20,000 over three years with expenses of £10,000” asked of by Michael Hooker for his company’s services as “fantastically high”. Ultimately, after nearly a year of corresponding with various fundraising companies, the University Appeal was back at square one.

The appeal aim of £2,000,000 was reconsidered, to take account of any potential shortfall from industry donations. Haynes wrote to Lord Cornwallis that “York and Norwich have both appealed for £1,500,000 and I am that certain that we cannot do with less”. Without this money, the envisioned five residential colleges housing 3000 students by 1970 would not become a reality.

The Appeal was showing signs of being in trouble. Donations simply weren’t coming in. On the 5th October 1964, Sir Cecil Syers, head of the Appeal committee, wrote that it was “unrealistic to hope for more than, at most, £1,250,000” in philanthropic donations, less than half of the original appeal aim.

This would be enough to build the first three colleges. It would be a while before even this preliminary goal was achieved. In retrospect, the use of professional fundraisers in place of Rootes’ personalised approach may well have benefited the early appeal and allowed construction to take place as planned. The tongue is not mightier than the pen, when the pen is wielded by those with experience.