This blog is our way of raising awareness. As White people, we are not claiming to be experts on this, but we have learned a lot through our work with Athena Swan and EDI at this University and we want to encourage discussion and keep learning. We would love to hear your suggestions in the comments section below.

What does it mean to be an ally? Can one declare oneself an ally, in the same way you might say “I’m a feminist”, but without really doing anything to assert this nominal title?

We might be firmly and passionately supportive of BAME colleagues, attend the #BLM marches and clearly assert our allegiance. We might be shocked by the news of racism across the world, and feel saddened by the injustices we see around us. At the end of a working day we may even go home and talk to our friends and family about the uncomfortable remark someone made in a meeting that day. But is that really enough?

In Higher Education and in many other workplaces, racism happens every day. It is mostly not the kind of racism that you can easily see or challenge. It is microagressions, structural inequalities, repressed feelings, silenced voices, lack of visibility and lack of support. It is hidden. And precisely because it is hidden, it is very dangerous. We get lulled into complacency: imagining that racism happens in other places, but at the University we are intelligent academics who work in a post-racist space. We have BAME colleagues whom we love and value (with a recognition that we wish there were more of them among us), who don’t often tell us if/when they experience any issues, and for this reason we may think that racism does not exist in Higher Education. We get the impression it is all fine, when it is not.

A member of staff at Kent explained that:

‘A core issue that is not addressed enough is the experience of microaggressions and just as important the absence of micro-affirmations. BAME staff are accustomed to experiencing “the odd slight”, disregard or disrespectful treatment by other staff, and sometimes more explicit “toxic hostility”. Equally important and perhaps even more common is not being afforded the positive recognition, the respect, the affirmations and opportunities to belong and to connect that white people give each other – That absence of affirmation is not spoken of so much but is pervasive, it is wearing and is hard to respond to effectively. That differential experience of affirmation is a key aspect of white privilege and conversely of racial exclusion and inequality’.

Just because we cannot always see racism in Higher Education, does not mean that we can sit back and not do anything.

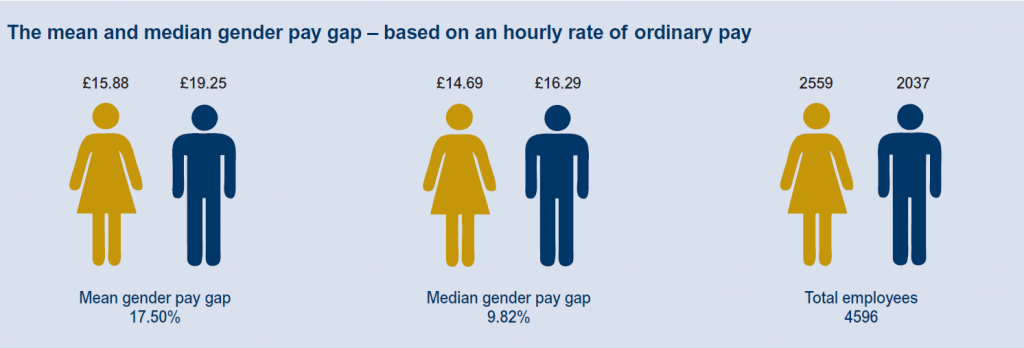

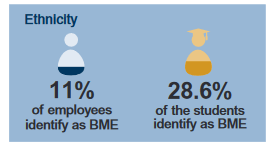

At the University of Kent, 28.6% of our students are BME.[1] Only 11% of our staff are, and even less in senior positions (10.5% in managerial and professorial positions).

How does this affect students? We know that there is an attainment gap for BAME students, something that the Student Success Project works hard to minimise. BAME students have fewer role models, and post-graduate students are likely to have less senior academics from a BAME background to support them.

How does it affect BAME staff? We know that staff from BAME backgrounds are less likely to apply for promotion, and also less likely to achieve promotion after they have applied. From the institutional Athena Swan team’s research, we know that many BAME staff members feel that white staff members (in particular males) get more informal support, praise and encouragement to step up the career ladder.

HOW TO BE AN ALLY

So if we want to be more than a bystander, more than an active supporter, and help beat the current system; what should we do?

Speak Up

Speak Up

Talking about race and inequalities can be uncomfortable. We shy away from the topic for fear of saying the wrong thing, upsetting someone, coming across as racist or stepping on someone’s toes. But NOT talking about race has worse consequences. If someone says something inappropriate in a meeting (like making fun of a foreign-sounding name of a colleague for example), make sure to challenge it in a calm and reasonable way.

Challenge yourself and Learn More

Challenge yourself and Learn More

Where to begin?

“There’s not time in the day to educate myself on all of this, there’s too much and I have no hours left in the day”… Yes, there is time. If you can’t fit in reading, then listen to a podcast while cooking, driving or hanging up the laundry. For example https://www.aboutracepodcast.com/ or https://www.thediversitygap.com.

Change your usual Netflix series to something that will widen your understanding about race. Netflix in fact has a whole genre for Black Lives Matter that you can browse. Consider what the world would look like if racial privilege was reversed by watching (or reading) Noughts and Crosses on BBC iPlayer. Also consider watching this lecture on White Privilege in Universities.

Mentor Junior Staff

Mentor Junior Staff

Take the time to support and encourage junior staff members, share advice and give nudges towards positive career choices; regardless of the person’s race or gender. PhD candidate Orielia Egambaram wrote about her experiences of race in our last blog. Keep in mind in your interactions with staff and students that what Orielia described are the kinds of experiences that are commonplace and persistent for BAME colleagues.

Challenge Your Unconscious Bias

Challenge Your Unconscious Bias

Higher Education is a space of White privilege. Many recognise this, but often those who benefit the most from this privilege do not. Throughout our research, we have found that often those who are already aware of and recognise their own unconscious bias are the ones that take training and resources seriously around this. Those who actively believe that they do not have any unconscious bias appear to pay less attention to training and information. If you believe that you don’t have an unconscious bias: think again. Learn more about your White privilege, for example through this TED Talk by Peggy McIntosh and do the available training that the University provides, including unconscious bias training.

Get Actively Involved

Get Actively Involved

Familiarise yourself with local action, such as the Decolonising the Curriculum Manifesto.

Be aware of important cultural events. If it is Ramadan, consider how fasting might impact on your students and colleagues, and be mindful that for example Christmas is not an event everyone celebrates. When it’s Black History Month, find out what events are taking place and attend and promote them. To help you with inclusiveness throughout the year, print an ‘inclusion calendar’ and keep on your desk.

The University of Kent has recently committed to signing up to the Race Equality Charter, which will mean a serious reconsideration of how we challenge our current norms and build a MUCH more inclusive workplace. Take interest in this process, make your school, your group, your division and your colleagues aware and accountable. Signing up to a charter is not the solution – it is a way of making sure that changes that need to happen, are implemented at every level.

REMEMBER if you are a White colleague and feel a bit uncomfortable thinking or doing anything about this your moment of discomfort is nothing compared to the impact of the daily drip of hostility and microaggressions that your BAME students and colleagues experience.

Blog written by Carin Tunaker and Sarah Vickerstaff.

[1] At the University of Kent, data is collected for BME staff and students, rather than BAME. This data is from the most recent University EDI Report.