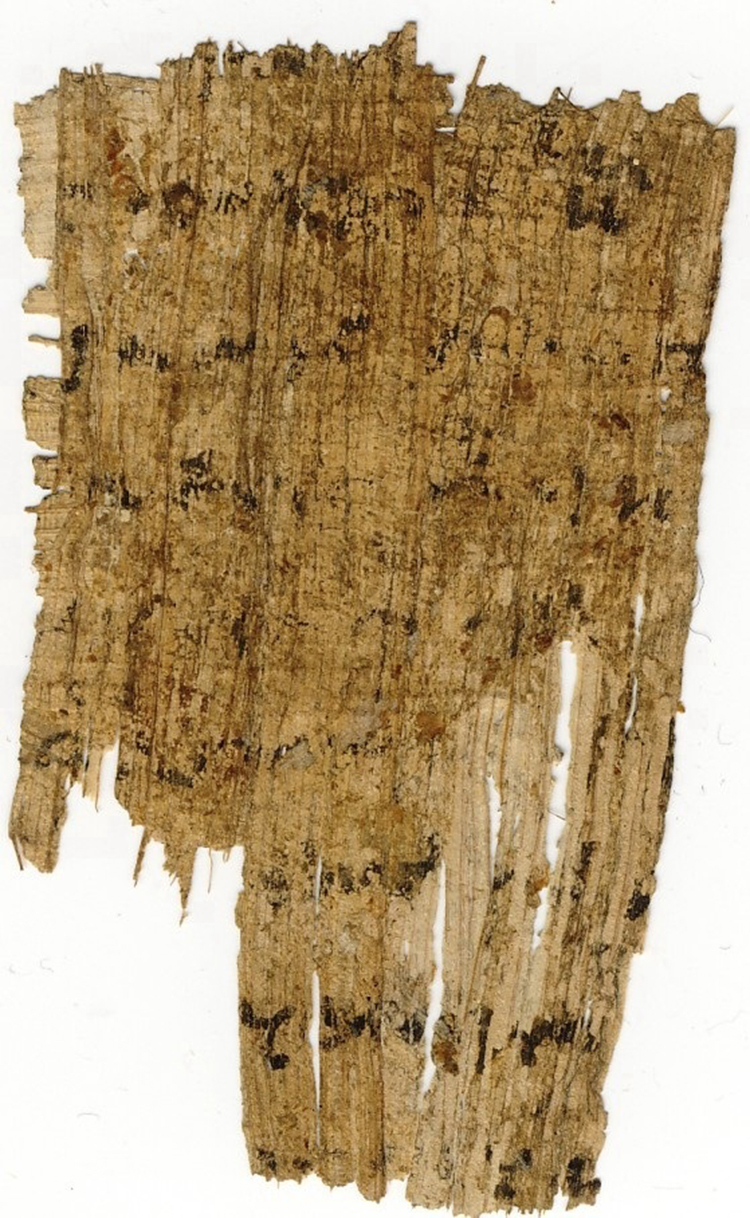

G 54775 Verso No 2

G 54771-6 verso: For the dimensions of the 31 individual fragments, see CPR XXVIII pp. 61-157. Date: about 210 – mid-II century BC. Provenance: Arsinoites (region of Tebtynis?). For the dating, provenance, palaeography and the general content, see the description of G 54771-6 recto. The list on the verso is arranged differently from that on the recto. The figures to the left of some sections of the text show that these were day dates of a particular month (on the verso of inv. no. 54771 the continuous sequence 11, 12, 13 and 14 survives). The hurried and cursive handwriting, the economical layout of the text and the fact that practically all entries are closed by a figure suggest that this is a list of tax payments made by individuals on particular days. As these payments were made day by day, the scribe seemingly entered the names and patronymics or familial or occupational designations of the taxpayers hurriedly, leaving little space between the entries. The varying figures at the end of the entries suggest that part-payments were also accepted towards the full amount of the tax due, depending on how much individuals could afford to pay. This system of paying tax is well known in Ptolemaic Egypt. The clerk obviously needed such a daily account of payments to keep track of the tax revenue flowing in. At a certain point in time he needed to check who had paid his dues and who had not. Therefore, he probably took the list on the verso and entered the sums it contained into a register of taxpayers, which was very similar to that on the recto (cf. the fact that probably the same individual appears in inv. no. 54771 recto col. II.34 and 54776 fr. 1 verso col. I.13; in 54771 recto col. II.27 and 54771 verso col. III.42; in 54771 recto col. II.30 and 54776 fr. 1 verso col. I.9; and in 54776 fr. 7 recto 10 and 54776 fr. 1 verso col. II.22, suggesting that essentially the same taxpaying population was concerned in both the recto and the verso of the once-complete papyrus roll), putting an x-shaped check-mark against those entries on the verso which had been entered into the register. Alternatively, it is possible that those individuals against whose names no figures appear on the recto were exempt from paying for some reason (e.g. being under age or infirm). Thus, the two lists appear to have had complementary functions but served the same overall purpose of tax collection from essentially the same taxpaying population. As the list on the recto had a different function from that on the verso in the same general process, it is impossible to tell whether the two sides concern tax collection in the same year or in two different years. What seems clear, however, is that the scribe is unlikely to have used the list on the recto with that on the verso at the same time, since turning the roll over when copying data from the verso to the recto would have been awkward from a practical point of view. This hypothetical reconstruction would explain well what would otherwise at first sight seem to be puzzling facts that not all names on the recto have figures against them; that the figures appear to be later additions; that the figures against the entries vary but not too widely or randomly (40 [?], 60, 75 [?], 80 [?], 90, 100, 120, 140, 160 [?], 200 [?], 220, 440, ?20, ?50), being almost always multiples of ten; and also the differences between the script and spacing of the recto and the verso. The papyrus was published by C. A. La’da as CPR XXVIII 9.