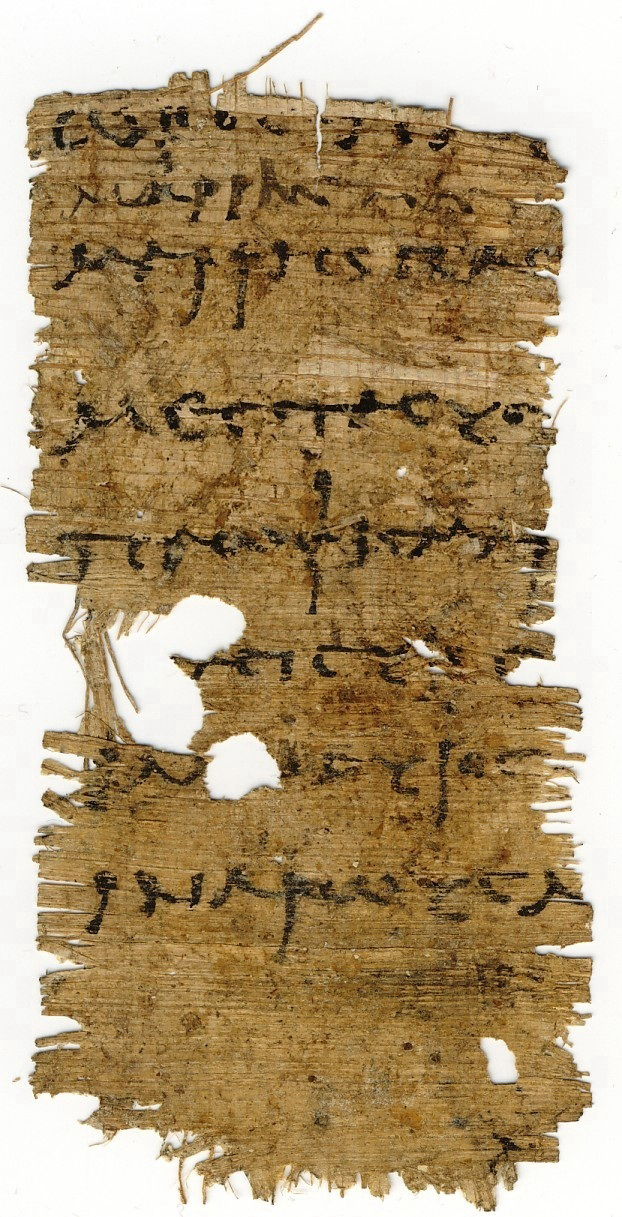

G 54772 Recto

G 54771-6 recto: For the dimensions of the 31 individual fragments, see CPR XXVIII pp. 61-157. Date: about 210 – mid-II century BC. Provenance: Arsinoites (region of Tebtynis?). The handwriting on both the recto and the verso has the same style of bilinear documentary handwriting (slower and more careful on the recto and faster and more cursive on the verso and in the later additions on the recto) quite typical of the end of the third and the first half of the second centuries BC. In the absence of a date in the documents and of any external evidence (for example, archaeological evidence, information supplied by the dealer about the provenance or information contained in other texts found with this papyrus), the dating of this papyrus has to rely on indirect internal indications in the texts and the palaeography. The symbol for talanton, which occurs at several places in this papyrus, shows that the figures at the end of most entries are sums of money expressed in drachmas. These sums of money (e.g. 220 and 120) are most realistic in the period after 210 BC and, particularly, between approximately 183 and 130/127 BC. Before this period the sums of money occurring in our texts would be too high and after it too low in comparison with the prices of, for example, grain, wine and labour. In addition, the fact that (with only two possible exceptions) no fractions of drachmas occur but almost always in multiples of ten also indicates the use of the copper standard. This conclusion is supported by the palaeography, which suggests the end of the third and the first half of the second centuries BC. The texts contain no place names and, unfortunately, no external information as to the provenance of these fragments is available in the inventory books of the Vienna Papyrus Collection. We can, therefore, only rely on indirect internal and external indications. The fact that these fragments were recovered from cartonnage suggests the Fayyum or other parts of Middle Egypt as their place of origin. Further, the mention of a Souchieion suggests a region of Egypt where Souchos was a prominent part of local religion to the extent that temples were dedicated to him. In a Middle Egyptian context this also points to the Fayyum. Finally, the onomastic material found in the texts also suggests the Fayyum for a number of reasons. First, the prevalence of Souchos names, particularly Petesouchos, is striking. Secondly, the onomastic material is generally very similar to that found in the papyri originating from Tebtynis and its region. Thirdly, some of the personal names which occur in these fragments, such as Papnebtynis and Phemroeris, appear to be typical specifically of Tebtynis and its region. These facts strongly suggest that our text comes from Tebtynis or the surrounding region of the southern Fayyum. It seems therefore probable that the Souchieion mentioned in our papyrus is the Souchos temple in Tebtynis or perhaps in Kerkeosiris. The precise content of this fragmentary papyrus is difficult to define owing partly to its highly fragmentary state of preservation and partly to the lack of close parallels. What is clear is that the recto and the verso each contain a list of exclusively male personal names which are in most cases followed by the father’s name or by either of the family terms hyios and adelphos, or by an occupational designation, such as kerameus, lachanopoles (?) and balaneus (?). In a few cases the adjective kophos and on one occasion perhaps also cholos, designating particular physical disabilities, appear. As some rare names (e.g. Harongoys) stand on their own, it appears that the addition of a patronymic or any other element after the name merely served the purpose of identification. As no reference to slaves occurs in the texts, these men must have had a free legal status. On the verso practically all, whereas on the recto only some, of the entries are followed by figures, which designate sums of money. The most logical interpretation of these facts appears to be the following. This document contains two lists, which served taxation purposes. As no tax is explicitly named in these lists, it is unclear for the collection of which tax they served. However, from the fact that exclusively masculine names are included it is logical to conclude that only men paid this particular tax. Further, the relative uniformity of the figures (220 and 120) on the recto suggests that some general tax was paid probably at the same rate (220 drachmas, this figure being the most common one) by all (see further below). Alternatively, the mention of a number of occupational designations might suggest that a variety of taxes were collected on the basis of these lists, including also occupational taxes. The small number of occupations named in the text and the relatively small number of individuals for whom an occupation is provided do however weaken this argument substantially. In addition, it appears far more likely that occupational designations, just as patronymics and other terms found after personal names, merely served the purpose of identifying individual taxpayers. The list on the recto appears to be a geographically-arranged register of taxpayers, presumably once complete. The free male inhabitants of perhaps Tebtynis or Kerkeosiris appear to have been listed household by household, arranged according to particular districts of that settlement. That the complete free male taxpaying population was registered is also suggested by the widely diverse nature of the occupations mentioned. The head of the household was registered first, followed by his male relatives (adelphos and hyios). The register was probably drawn up in an exercise going from house to house in particular districts. One of the largest fragments, inv. no. 54776 fr. 1 recto, partially preserves a list of the free male inhabitants probably of a district named after the local Souchos temple as no priestly titles or other references to a cultic context are provided for the individuals listed. Indeed, it is unlikely that so many priests of probably the same tax status would have existed in one temple unless, of course, it is assumed that the list of the priests of the Souchieion came to an end in the unpreserved lower part of column II and that column III contains a list of an entirely different group of men, an assumption which appears most unlikely. The slow and clear writing and the generously spaced layout of the text suggest that it was prepared with care and under no particular time-pressure. The generous spacing also suggests that the scribe expected subsequent additions to be made to the text. Further, it appears likely that the figures at the end of some of the entries, the interlinear additions and the brackets were inserted at a later date in more cursive handwriting, the same script which is used on the verso. The papyrus was published by C. A. La’da as CPR XXVIII 8.