The following account is an attempt to describe the importance of the university, both socially and academically, and the surrounding countryside to my personal development as a social scientist. It arose form a recent talk I gave to alumni from the Second 500 during a lunch gathering on 22 February this year.

I have purposely placed the early years of my career into the foreground to illustrate how people and events interconnect so that what might look like a well-laid plan is typically a balancing act between searching for knowledge, happiness, and enlightenment.

The last thing I want to do is to appear self-satisfied or ‘smug’. I have intentionally omitted the more painful events that life throws at us whether they be failure, illness, or bereavement because they are the personal challenges we all have to meet to some degree. I am also very much aware that as we grow older the narrative describing our journey through life changes as we reflect and look forward to the future, including joint pain and the joy of grandparenting.

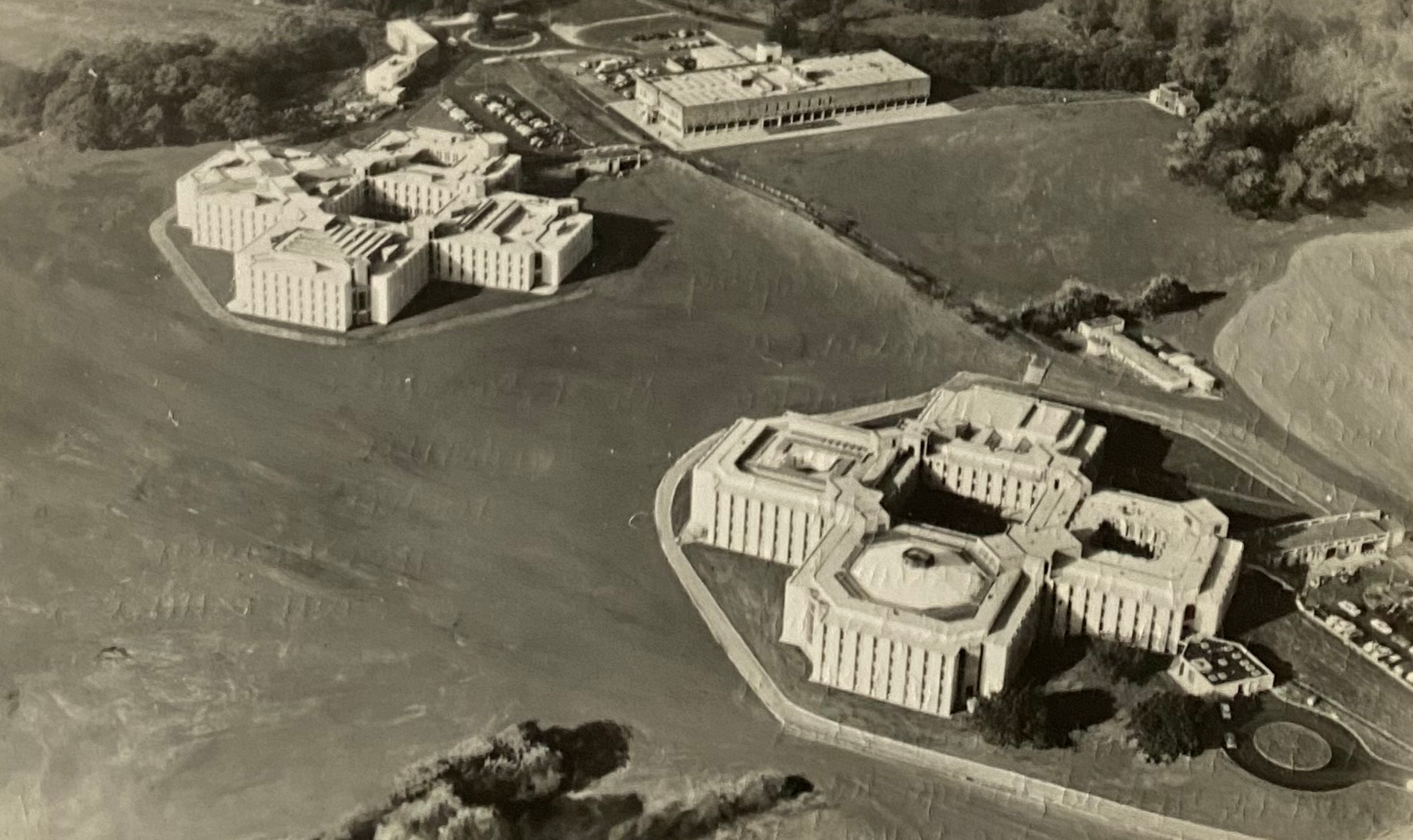

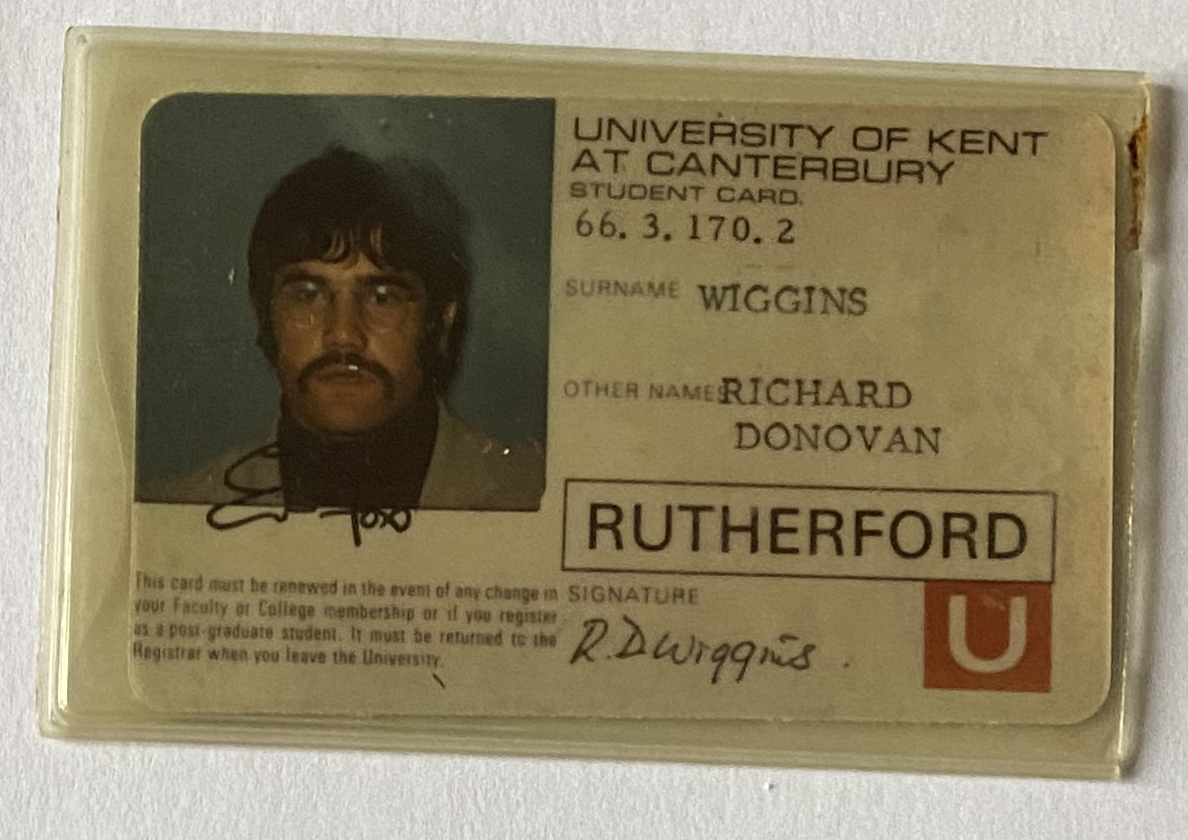

Almost sixty years have passed since I first stepped into Rutherford College to register for the first day of term in 1966. I can still remember the smell of the wooden handrails and the salty air. I had arrived at my lodgings in Herne Bay the previous evening; Mortimer Street was to be my home for the next three terms. Despite having five or six natural scientists at the lodgings I felt quite lonely. Walking to the end of the pier with my parents to say ‘goodbye’ on the Sunday had been a strong yet, sad marker of separation.

In fact, due to poor transport links, Sundays were the days that I got to know Herne Bay; coffee in Macaris and occasional trips to Dreamland in Margate in the evening to see live bands like the Kinks. It wasn’t long before I met a couple of friendly fellows at the bus stop in the High Street for a bus to the University, Aidan Kelly and Alan Bryman (now deceased). Aidan and I were enthusiastic rugby players and we eventually shared a room in Mortimer Street that summer. He introduced me to jazz and he still keeps me posted with music. Although he never quite converted me away from ‘Johnny Kidd and the Pirates’

My main criterion for choosing Kent to study was its proximity to the sea which derived from having been born in Birmingham and living in the Midlands most of my life. Herne Bay was an extension of bed & breakfast holiday escapes in my childhood and my Uncle Bill’s annual family holidays in Cliftonville. The second criterion for study was to play safe and obtain a profession. A BA in Accounting fitted the bill and matched my father’s adage that “if you don’t get a trade get a profession” in tandem with the comment “that a degree was a ticket for life”. These words resonated at the time of choosing to major in accounting after Part One.

Another key influence on my decision making was that I had grown weary of studying A Levels in Mathematics and Physics. The broad-based social science offer in Part One was really different, I gained a better knowledge of politics and history together with sociology and economics. It was hard to write essays after two intense years of studying calculus and matrix algebra. Having embraced social science I still didn’t have the confidence to break-out and elect sociology which was a fascinating way of understanding my lived environment. I was always proud that Julienne Ford had tried in vain to persuade me to stick with sociology. Little did I know that much later that I would spend sixteen years in a sociology department at City University, London.

Another new friend, John Digance, helped broaden my appreciation of literature. Ironically, I’d always boasted that I had only read one book for pleasure before I came to Kent. He took that on board and set me to task that every week I should read and discuss with him a book from his English reading list. The experience really awakened in me a love of literature beginning with Hemmingway, Steinbeck, and Camus. At that time it was always a ‘must’ to have an interesting title to display in your overcoat pocket!

My second year was spent in Rutherford and my fun neighbour was Trevor (aka Graham) Beeton. Apart from Daniel Rubin, a fellow student of accounting, Trevor was one of the first people I’d ever befriended who had been to public school. Trevor and I went on to share a flat in Abbey Gardens near the Abbey Road studios of Beatles fame after we graduated. At that time I was a statistical assistant in the ‘Research & Intelligence’ Unit of the Greater London Council in County Hall (now an aquarium).

During the second year I spent more and more time in Canterbury with women friends from the Art College then, near Westgate. It was at party that I met Jenny, my future wife and lifelong companion. Her flat was most conveniently situated along Whitstable Road, half-way between the university and the ‘Bell and Crown’. Towards the end of the second year we were required to undertake additional month’s study termed the ‘long vacation’. Its title gave the wrong signal and many days were spent on the beach in Broadstairs.

During the end of that year I had been elected as captain of the UKC Rugby 1st XV for the following season. It was to prove a successful year on the pitch as we reached the UAU Southern Division semi-finals in Newcastle and I gained a place in the UAU squad to play Sussex County (proud to say that team-mates included Andy Ripley and Tony Neary).

My ambition was to continue playing for the UAU and enrol on a new MA at Kent in Quantitative Social Science (QSS). The latter was an attractive niche as my aptitude for numbers as a means of understanding society came full circle. However, rugby eventually lost out to work, study and romance.

Social accounting became an alternative to articles but it was not to be at first. The plan was to combine my love of the game and to remain in Canterbury with Jenny who had two more years of study at the Art College. Sadly, my degree didn’t prove good enough to be funded for the MA programme so I accepted a place at Exeter University to train to teach Economics and I was invited to train with the England UAU squad that summer at Bisham Abbey. Neither outcomes matured. I left the training squad and headed back to Jenny. I took a chance and moved to London and after a few weeks unemployment I was offered a post at the GLC.

Those GLC days were formative. Sitting in a shared office with a hand calculator bigger than most of today’s laptops reporting to a statistician in Planning & Transportation. Statistical modelling with a powerful calculator was time consuming and I soon learned that my introduction to the subject was not sufficiently strong to make progress in the profession. I enrolled for the Institute of Statisticians evening classes at the Regent St Polytechnic (now the University of Westminster) but, three evenings a week proved tough after the privilege of daytime study at Kent.

Fortunately, at that time the prime minister Harold Wilson, himself a former Home Office statistician, supported the idea of conversion courses for people like myself to qualify as statisticians. In 1970 I enrolled for a postgraduate Diploma in Statistics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). This was a ‘dream ticket’, no more evening classes and an opportunity to enjoy the freedom of a fully funded course of study with no obligation to return to the GLC.

In order to retrieve the 1969 plan Jenny and I married at Croydon Registry Office in the summer of 1970 prior to moving to Whitstable so she could complete her degree in Fine Art and I could commute to LSE. The commuter trains in those days went into Cannon Steet or London Victoria and were just as fast as today.

In the following year we moved to South London and I began my first entry into the civil service at the Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) and Jenny completed a postgraduate teacher training certificate at Hornsey Art College. Being a civil servant didn’t quite fit at that time and soon my appetite for learning took me back to LSE to complete a Masters in Statistics followed by study for a PhD in Survey Methodology. It was to take me as long as Durkheim to complete the thesis for reasons which will become apparent.

Prior to commencing the thesis I was persuaded by my supervisor to work on a large scale All-Ireland study of occupational mobility based at Queen’s University, Belfast and the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin. Living and working in Ireland both North and South proved to be a massive experience which has sustained an interest in the politics of the Emerald Isle throughout the rest of my life as well as being a practical lesson in how to conduct a large-scale social survey in the North of Ireland during a period of conflict (1973). During this time our car was written off, the pub at the end of the road where we stayed was blown up and our son was conceived.

Being a father whilst a student on return to London was an amalgam of idealism about parenting and further study. I really thought that whilst Jenny worked as an art teacher in Catford I could combine being a house-husband with research (largely a return to ‘brute-force’ algebra at that time). We were sharing a house in Lewisham at the time with two friends, one from Canterbury Art College and another, Mike Mulholland (Eliot, 1965).

Looking after a child where there is no hot water is tough so Jenny and I aspired to find a place of our own in 1975. To pay a mortgage required more than a teacher’s salary and my grant income so I applied for a job as a statistician at the Institute of Psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital. The PhD was on the back burner but we were lucky enough to find a suitable property in Lewisham.

After a couple of years in epidemiological psychiatry working on studies of aircraft noise and the development of the General Health Questionnaire in the community I moved into community medicine at St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School in 1977. During my stay there our daughter Kate was born. A boy and girl now defined our family. It was very important to me to spend time with the children and at that time I noticed that two close friends had secured jobs in London polytechnics and were enjoying the benefits of long summer holidays with their families.

I joined their ‘club’ by securing a position at the Central London Polytechnic (previously Regent Street and now Westminster Uni) in Social Statistics. By the end of the 1980s the privileges of long holidays had waned and the pressures of publishing for research assessment exercises began to dominate. Whilst I had published work as part of my roles in epidemiology the PhD was still on the back burner and it had become almost necessary as a means of career progression in academia. In 1988 I moved to LSE on a fixed-term contract for two years as a lecturer in the Statistics Department. The reality of a 50% reduction in my face-to-face teaching obligations released time and energy for active research and final submission of my thesis.

At the end of my term at LSE I was persuaded to return to the civil service as Deputy Director of the 1991 Census Validation Study. A grand opportunity which revealed estimates of the missing half-million subsequently revised to the missing million. During this time I learned how important keeping to budget had become. Accounting never leaves you but, for me the call of the classroom was stronger than a civil service career and I began a new post as course director of an MSc in Social Research Methods and Statistics at City University, London. Another circle was formed. The disappointment of not being accepted on to the MA in QSS at Kent but having developed a passion for quantitative social science with a desire to teach non-specialists and specialists alike the time was right. The establishment of quantitative methods training for social science postgraduates was being promoted by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the City Master’s programme was a bespoke response the ESRC’s ‘New Horizons in Social Science.’

Teaching postgraduates and supervising PhD students at City helped consolidate my contribution to quantitative social science and methodology. I had always considered that that applied statistics teaching was best served by those who practiced and to that end the themes of research projects fuelled what I brought to the classroom namely, children’s well-being, health inequality, the study of quality of life in early old age (gerontology), money management in heterosexual relationships, the use of the internet to conduct qualitative interviews and the study of resilience.

Given my skill set, there were also interesting opportunities for consultancy work, for example an evaluation of the Home Office for the government’s ‘Safer Cities’ programme and work for KPMG on sampling. Throughout those busy years we were regular visitors to Herne Bay and Whitstable with the children. First stop, the amusement arcade in Herne Bay by the pier. We bought a beach hut in the 1980s as a refuge from the short winter days and northerly winds and a base for swimming and sailing.

In 2007 I moved to the Institute of Education as Head of QSS (now a Centre within UCL’s Social Research Institute). I swopped Exmouth Market in Clerkenwell for the pleasant squares around UCL in Gower Street. I began each day with breakfast in Russell Square and managed to clear my emails before most colleagues arrived for work. In 2013 our wonderful bundle of joy, grandson Lyle, arrived and I reduced my hours at work in an endeavour to be available to help with his care and most of all, to have fun.

During the pandemic I decided to retire, although I have continued to write research papers and edit a series of books in recent years so as not to be a nuisance to my wife who works tirelessly as an artist in her studio near the Thames Barrier.

Our respite retreat is now a little chalet referred to as the ‘cabin’ in Seasalter. We are still very attached to the Kentish landscape, walks, swimming and attending the Whitstable Sessions as members of a ‘hush’ audience to listen to Americana music run by fellow alumni Johnny and Anna Fewings. Increasingly, retirement brings new opportunities for study and cultural appreciation, notably poetry and film with adult education tutor, John Digance (mentioned earlier). Another circle in the process of completion which is always preferable to a straight line.

To conclude with a quote from Samuel Smiles, 1812-1904:

“Life will always be to a large extent what we ourselves make it.”

Dick Wiggins, Rutherford, 1966-69.