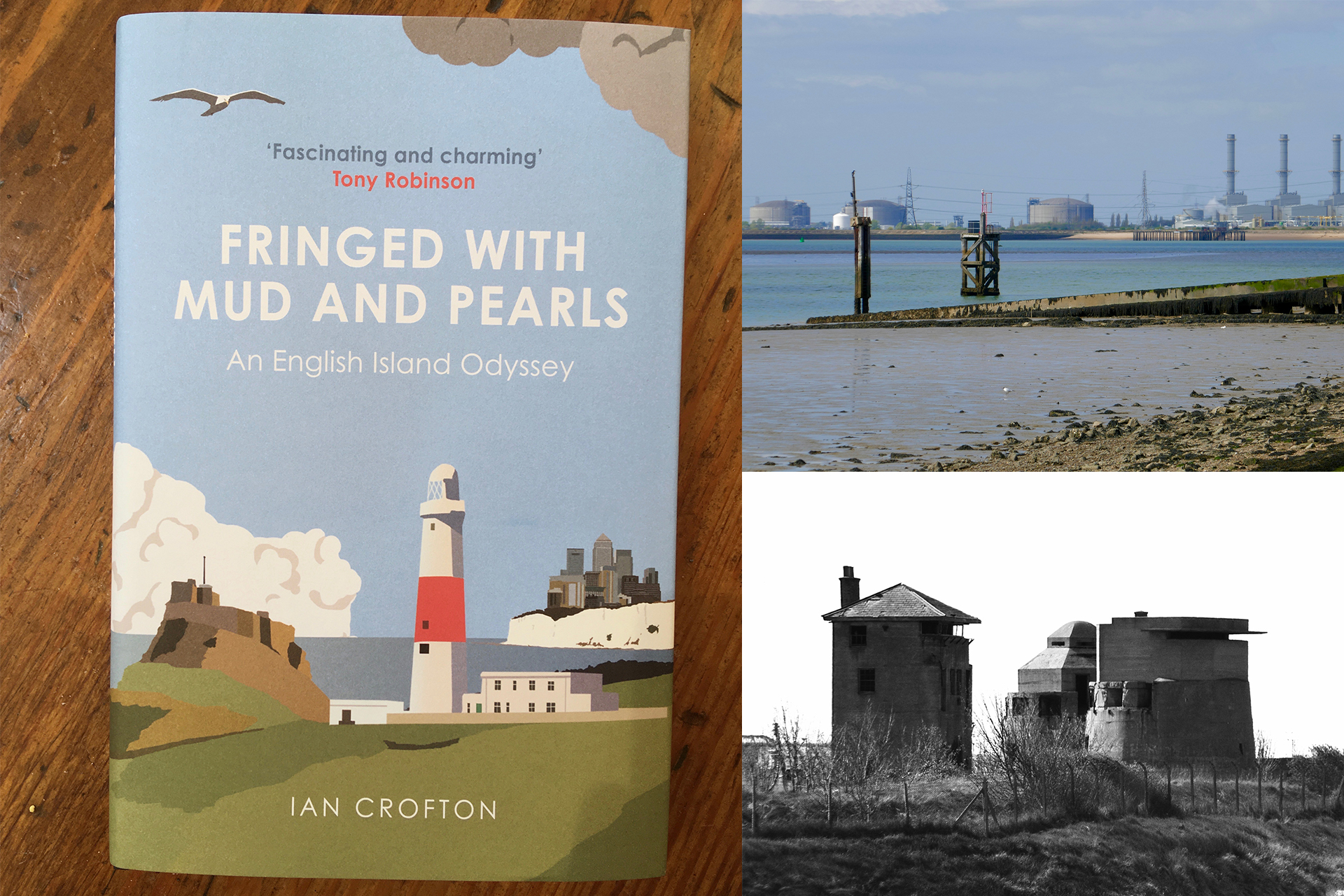

Ian Crofton (Rutherford College, 1972-5, English and American Literature), has just published his latest book, ‘Fringed with Mud and Pearls: An English Island Odyssey’ (Birlinn Books) and you can find more information about the book, plus a short video, here!

This autumn also sees the publication of the second edition of Ian’s ‘Dictionary of Scottish Phrase and Fable’ (Birlinn, 2012).

You can read a sneak preview of Ian’s book below. This chapter is about the Isle of Sheppey, the only Kentish island included in his book.

You’ll have a blast

THE ISLE OF SHEPPEY

I met Baz the fisherman on the quay by the creek called the Creek at Queenborough. I’d got off the little local train one stop before its terminus at Sheerness. My intention was to make the last mile or so of the journey on foot, along the Medway shore of the Isle of Sheppey.

Baz was untangling nets, hauling yards and yards of blue-green plastic line from the back of a pick-up truck. I’d passed by a boat sitting on the mud of the creek with bunches of flowers tucked all along the taffrail, around its cockpit and cabin. I asked Baz about the flowers. ‘The old dad died,’ he told me. ‘He owned the boat. Now his sons, on birthdays and other special days, decorate it with flowers.’

There weren’t many working fishermen left on the Isle of Sheppey, he said. ‘In the 80s there were fourteen boats running out of here commercially. Now we’ve only got two or three.’ He fished mostly for skate, and worked the local beds of whelks, mussels and oysters. There were also cruises for sea anglers and seal-watchers in his boat Stella Spei (‘star of hope’ he explained) and trips out to the Red Sands Towers. The Towers were Second World War anti-aircraft forts positioned in the middle of the mouth of the Thames Estuary. ‘The men were posted out there for six weeks at a time,’ he said. ‘They had some pretty big guns.’ He told me many German bombers just dropped their loads over the sea and turned for home rather than run the gauntlet of fire they’d face as they flew up the Estuary towards London. So there were a lot of unexploded bombs scattered across the sea bed.

‘Also you’ve got the Richard Montgomery wreck just off Sheerness,’ he added as an afterthought. ‘American munitions ship.’

‘The one where you keep your fingers crossed?’ I asked. I’d heard about the Richard Montgomery before my journey to Sheppey, and felt its faint threat hang over me as I approached Sheerness. ‘You don’t go too near that do you?’

August 1944: the SS Richard Montgomery – a US Liberty ship named after an American patriot killed fighting the British in 1775 – took on a cargo of munitions at Hog Island, Philadelphia, before sailing down the Delaware River and across the Atlantic. When it arrived at the mouth of the Thames Estuary, the harbour master at Southend, in charge of all shipping movements in the Estuary, ordered it to take up a berth in the Great Nore Anchorage while it waited for a convoy to assemble. Then it was to sail across the Channel to Cherbourg, liberated by the Allies just a month earlier.

On 20 August, while its captain slept, the Richard Montgomery dragged its anchor. Several ships nearby saw it shifting, and sounded their sirens in warning. To no avail. The Richard Montgomery ran aground on a sandbank at the entrance to the Medway channel, just a mile and a half off Sheerness. When the tide fell, the ship broke its back. Attempts to salvage the cargo were abandoned a month later when the hull snapped in two, leaving some 1400 tons of high explosive still on board. The munitions included – and still include – 286 ‘blockbuster’ bombs, each weighing 2000 lb, and so named because each one was – is – capable of destroying a whole block of buildings. The wreck also contains several thousand 1000 lb bombs, and 2500 cluster bombs with their fuses in place.

The ship’s three masts can still be seen sticking above the water at all states of the tide. The whole area round the wreck is an exclusion zone.

The authorities insist that there is little risk of an explosion. Others say it is a real possibility. In 2004 the New Scientist concluded that if the ship went up it would be one of the biggest manmade non-nuclear explosions of all time. A column of debris would be thrown nearly two miles into the air, a tsunami would power up the Thames towards London, Sheerness itself would be devastated, and, if hit, the tanks of liquid gas on the Isle of Grain, across the mouth of the Medway, would unleash a further inferno.

Experts say that the explosives should remain inert unless exposed to sudden shock, friction, or heat. But the annual surveys by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency suggest the wreck is slowly disintegrating, so a sudden collapse leading to a mighty detonation cannot be ruled out. There have already been a number of near misses with vessels in poor visibility. ‘If this boat had gone down outside the Houses of Parliament,’ complained one local councillor, ‘something would have been done long ago. How far down the river do you have to go before a dangerous wreck becomes acceptable?’

At the edge of the town of Sheerness there’s a mural that greets visitors. It depicts a sour-faced mermaid lying on a beach with the masts of the Richard Montgomery emerging from the sea behind her. The mermaid has one hand on a plunger marked ‘TNT’. The wire leads across the beach and into the sea, towards the wreck. The mural declares

Welcome to SHEERNESS

You’ll have a blast

‘You don’t go too near that wreck do you?’ I asked Baz.

‘Well the funny thing is,’ Baz said, ‘when we’re dredging for mussels, any bombs that we pull up, we’ll wait till we’ve got half a dozen on board and then we drop ’em round the perimeter of the wreck, so we don’t keep picking the same bombs up again and again.’

I asked whether it wasn’t a bit nerve-wracking hauling up all this dangerous material.

‘A little bit,’ he conceded. ‘The big ones can be a worry. Years ago they used to just drop ’em back down, but what we do now is call up the MoD. They’ll come out. They pay compensation for your down time. Years ago it weren’t like that.’

Sometimes there were naval mines, he said, ‘the big ones with spikes coming out of ’em’. Sometimes he pulled up pairs of cannon balls linked together with a chain, of the sort used in Nelson’s era for snapping the masts of enemy ships, or the heads off enemy sailors. Nelson had trained at Sheerness, he told me, and is said to have shared a house in Queenborough with his mistress, Emma Hamilton. After Nelson’s death at Trafalgar, his body, preserved in a barrel of brandy, was supposedly landed at Sheerness. The naval dockyard there had been established by Samuel Pepys in the 1660s, and had only closed in 1960. The area round about the docks was called Bluetown, after the colour of the Royal Navy’s paint the workers had appropriated to decorate the huts they lived in. ‘Later,’ Baz said, a little sheepishly, ‘Bluetown was full of, well, you know, pubs and brothels.’

Being on the edge of England, the Isle of Sheppey has found itself in a number of England’s wars. Edward III built a castle at Queenborough to guard his supply ships making their way to France during the Hundred Years’ War via the Swale, the sheltered channel that runs west and south of the island, separating it from the mainland. The town is named after his queen, Philippa of Hainault.

Baz remembered that the Dutch had occupied the island – or at least Queenborough and Sheerness. This was in 1667, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, when the Dutch sailed up the Medway and destroyed the Royal Navy at anchor off Chatham, one of the greatest humiliations in English military history. The nation had, one contemporary mourned, ‘lost its honour at sea for ever’. Although the Dutch only held the Isle of Sheppey for a few days, more than one local told me that Dutch rule had lasted until the 1960s. In fact, in 1967 there was an official ceremony at which the Dutch formally handed back Queenborough to the UK.

By this time, or some time before, Queenborough had become a bit of a backwater. In the early 18th century Daniel Defoe described it as ‘a miserable and dirty fishing town’. In the 19th century, prison hulks were moored offshore, and the corpses of dead convicts were dumped on a nearby salt marsh. The place became known as Deadman’s Island. Rising sea levels and coastal erosion are leaving unmarked coffins and bits of bone sticking out of the mud, visible at low tide. Access to the island is prohibited. …