Category Archives: Uncategorized

Finest British pigs set to go to India to develop its burgeoning pig sector

A high-level delegation from the Punjab government has paid a visit to the UK to assess British pig production and genetics as the Indian state intends to develop its burgeoning pig sector. Further details can be found here.

Many births of the test tube baby

On 2nd March Nick Hopwood of the University of Cambridge gave the HG Wells lecture on ‘The many births of the test-tube baby’. It is generally accepted that following in vitro fertilization in Oldham, Louise Brown became the world’s first ‘test-tube baby’. Her birth, thanks to 2010 Nobel prize winner Robert Edwards, Patrick Steptoe and their team, was a major international news story in July 1978. Following much apprehension about such ‘implants’, the press celebrated Louise, a ‘miracle of ordinariness’, as making medical history. This was, however, far from the first claim to a test-tube baby; since 1944, various researchers had reported fertilizing human eggs to produce embryos and even infants. Nick highlighted two points about these reports. Some were made in journal articles, some in the general press and some in both. And some later announcements maintained far less than some early ones, a sign that standards changed. In 1969, for example, when Edwards et al. reported ‘early stages of fertilization’, not all specialists accepted even this, while others dismissed it as old hat. Rather than taking us through a litany of claim and counter-claim Nick gave us a deep insight into the manner, means and enthusiasm with which the claims were made and, equally the manner, means and vitriol with which opponents and colleagues assessed and contested them. Nick’s analysis focused on changes, on the one hand, in standards of evidence, and on the other, in norms of communication, especially the ways that scientists used not only learned journals and textbooks, but also newspapers and television. The most striking example was the birth of Brown herself, of which for many months the Daily Mail provided the fullest account.

For nearly 2 hours of talk and discussion, Nick intrigued a 50-strong audience with fresh perspectives on this, the founding achievement of reproductive biomedicine. He helped us grasp why some of the claims were more credible than others and why, after a far from certain beginning, and a good deal of controversy, the world agreed that Louise was ‘the one’. Nick ended with the point that, for impactful discoveries such as IVF, journal articles, however desirable, may be neither sufficient nor necessary successfully to stake medical and scientific claims. The Centres for the History of the Sciences (CHotS) and for Interdisciplinary Studies of Reproduction (CISoR) are incredibly grateful for Nick for his time and enthusiasm and hope to work together with him further in the future.

Postnatally depressed mothers reluctant to have more children

Mothers who have postnatal depression are unlikely to have more than two children according to research carried out by Kent evolutionary anthropologists.

Until now very little has been known about how women’s future fertility is impacted by the experience of postnatal depression.

A research team from Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conservation collected data on the complete reproductive histories of over 300 women to measure the effect postnatal depression had on their decision to have more children. The mothers were all born in the early to mid-20th century and the majority were based in industrialised countries while raising their children.

The team concluded that postnatal depression, particularly when the first child is born, leads to lowered fertility levels. Experiencing higher levels of emotional distress in her first postnatal period decreased a woman’s likelihood of having a third child, though did not affect whether she had a second.

Furthermore, postnatal depression after both the first and the second child dissuaded women from having a third child to the same extent as if they had experienced major birth complications.

The research by Sarah Myers, Dr Oskar Burger and Dr Sarah Johns is the first research to highlight the potential role postnatal depression has on population ageing, where the median age of a country becomes older over time.

This demographic change is mostly caused by women having fewer children, and can have significant social and economic consequences. Given that postnatal depression has a prevalence rate of around 13% in industrialised countries, with emotional distress occurring in up to 63% of mothers with infants, this research suggests that investing in screening and preventative measures to ensure good maternal mental health now may reduce costs and problems associated with an aging population at a later stage.

Article for Evolution, Medicine and Public Health (an open access journal)

Surrogacy Law Reform Conference – 6th May 2016

Surrogacy in the 21st century: rethinking assumptions, reforming law

Friends House, London, 6th May 2016

Surrogacy laws in the UK are now over 30 years old and look increasingly out of date. Within the same timeframe, assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) have significantly developed, and their place in modern society has become firmly established, both in terms of family creation and with regard to the extended medical research opportunities they provide. Surrogacy is a form of assisted reproduction, whether an arrangement requires the use of IVF, the storage of gametes of one or more parties outside of the body in a licensed setting, the use of donated gametes, or none of these. It is a legitimate form of family creation for those who have no other option to have their own child, and who exercise the choice not to adopt.

The law relating to ARTs was overhauled in 2008, but little changed in relation to surrogacy other than small and necessary extensions of the categories of people to whom a ‘parental order’ might be available. No consideration was given to the fundamental assumptions that underpin the entirety of the regulation of surrogacy. Since the law on surrogacy was created, we have also witnessed astonishing amounts of social change, not only in terms of who we consider to be ‘families’ or ‘parents’, but also in wider social acceptance of difference. In addition, the internet explosion has made surrogacy an international business, often raising both ethical and practical concerns when overseas arrangements are entered into from the UK.

This one-day event is designed to test and challenge the assumptions that underpin the existing UK law on surrogacy, showing how and why it has become out of date, in a variety of different contexts, and how it fails to protect the interests of children and families created via surrogacy. It draws upon and discusses the findings in the November 2015 report of the Surrogacy UK Working Group on Surrogacy Law Reform, along with reflections from a range of other commentators including Professor Margot Brazier and Baroness Mary Warnock, who each chaired government inquiries into surrogacy, publishing their reports in 1998 and 1984, respectively.

CAFÉ SCIENTIFIQUE: Should the State Define what makes a Good Parent?

Drawing on research carried out as part of the ‘Uses and Abuses of Biology’ programme, Ellie will talk about the rise of ‘neuroparenting’ and discuss how Government ‘early intervention’ policies based on dubious claims about neuroscience both undermine the autonomy of the family and tarnish science’.

6.30pm-8.30pm, Tuesday 8th March

YE OLDE BEVERLIE

St Stephen’s Green, Canterbury, Kent CT2 7JU

Dr Ellie Lee

Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies of Reproduction (CISoR)

The session will be moderated by:

Dr Ruth Cain, Kent Law School and CISoR

A light buffet will be provided

Thanks to the University of Kent Public Engagement with Research Fund

Policing Pregnancy:

‘How Can a State Control Swallowing?’ Medical Abortion and the Law.

The Medical Society of London, 12.45-5.15, 23 March 2016

Professor Sally Sheldon (Kent Law School and Deputy Director, CISoR) will launch the findings of her AHRC-funded research into the legal implications of abortion pills at this event, where she will be joined by a panel of speakers with expertise in relevant law, medicine and policy. A light lunch and drinks will be provided. Attendance is free but numbers are limited and advance registration is required. A small number of bursaries are available to support the attendance of students. For more details and to register, see here

Informed consent and ART

CISoR members, Sally Sheldon (KLS), Darren Griffin (Biosciences), Ellie Lee and Jan Macvarish (SSPSSR) are undertaking exploratory research into informed consent practices in assisted reproduction. The Wellcome Trust has awarded Sheldon a small grant (£4,242) to support a pilot study that will potentially laying the groundwork for a larger project. The work takes its starting point from the fact that infertility treatment services have sometimes been subject to accusations that profit has been prioritised over patient benefit, with patients encouraged to undergo costly, unnecessary, experimental treatments which are unlikely to succeed. However, there is little high quality analysis that allows for an objective assessment of the merits of such claims and little research exploring patients’ experience of informed consent in this area. The larger project will potentially aim to fill that gap.

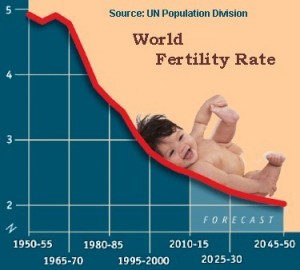

Global reduction in fertility – What’s going on?

In the first paper, Oskar and Daniel Hruschka of Arizona State University examine how the variation in fertility changes during a general overall decline. Many investigations have looked at changes in the average fertility behaviour, and have usually focused on national or county-level data. Hruschka and Burger however analyse individual-level data from the Demographic and Health Survey, looking at fertility data on women from 92 low- and middle- income countries. They show that a great deal of the variation among individuals is due to chance rather than to measurable individual differences. This means that chance might have more to do with fertility outcomes than characteristics such as education or wealth.