Carrie Etter – who as well as being an acclaimed poet, is also senior lecturer in Creative Writing at Bath Spa and editor of the important anthology Infinite Difference: Other Poetries by UK Women Poets – read last Wednesday from her third collection, Imagined Sons (Seren, 2014), some of the poems of which were part of a pamphlet from Oystercatcher called The Son, which was a Poetry Book Society Pamphlet Choice.

This collection of prose poems reflects upon giving up her son for adoption when she was seventeen – though, Etter said, she wanted to find her way to writing of difficult emotional experience that wasn’t confessional. She used, she said, in her early twenties, to write confessional poems – and confessional poems on this subject – but she has since found that by focusing on direct personal narrative, which often focuses on event– the hallmark of the confessional – she was not able to achieve her aim, that of bringing consciousness of the day-to-day experience of loss through in the collection. There is also a concern for the reader’s ability to access or feel, emotion, in works that are explicitly concerned with it. The best way, Etter said, to let the reader into emotion is not to tell of the emotion but evoke it for the reader to be able to experience it for herself.

This is achieved in the collection by a carefully structured pattern of four ‘Imagined Sons’ poems – in which meeting between herself and her son are imagined, sometimes told in a direct realist style, as in ‘Imagined Sons 11: The Friend (Part 1)’:

Coming out on the other side, I’m surprised I see no people, no one visible in the distance, only low sones, tablets of grey and black, occasionally a white cross, and I apprehend this is a –

And often filtered through fairytale, and, particularly Greek myth, as in ‘Imagined Sons 16: Narcissus’:

I break into sobs, and when the water of my tears laps at my feet, I know I’m here to drown us both

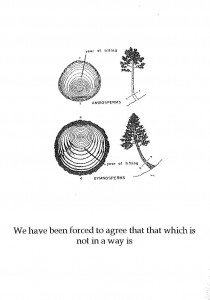

In other places, this refraction through myth becomes more riotous, as in the surrealist ‘Imagined Sons 9: Greek Salad’, a modern Metamorphoses in which her son, transformed into an olive tree for raping the keeper of the god’s olive grove, appears as an olive in her Greek salad. Having listened to him start to talk about the emotional neglect of his now keeper, Etter cuts him off, mid-whine, by eating him:

‘Delicious,’ I say to the waiter, swallowing the small olive whole. ‘Just delicious.’

The poems have their own logics, avoid any singular way of seeing or thinking about the experience of imagining encountering her son – she was surprised, Etter said, by the fact that she ate the olive – she hadn’t started the poem intending to, yet she was sure about it’s psychological accuracy, the way it followed through the logic of the poem.

These imagined son poems are then carefully divided by ten ‘Birthmother’s Catechisms’, so that every four imagined sons poems are followed by a catechism, which also bookend the collection. These catechisms came later than the imagined sons poems – it took a long time, said Etter, to realize that the question and response form of this genre of religious instruction was the right form to raise questions not only that weren’t able to be explored in the imagined sons format, but which were raised by that format. Consequently, these catechisms constitute a form of self-questioning (rather than, as with the religious model from which Etter takes her form, a mnemonic for learning answers by rote):

How did you let him go?

A nurse brought pills for drying up breast milk

How did you let him go?

Who hangs a birdhouse from a sapling?

In a collection that scrutinizes many imagined sons and encounters with them, these poems of self-scrutiny are, I would say, necessary. Etter too thinks so, saying that one editor who loved the imagined sons poems didn’t like the catechisms, thought they were a ‘mistake’. But Etter found them, not only necessary, but necessary as a regular structuring device, giving a more complete sense of the day-to-day experience of loss a birthmother has. This very careful ordering, led to questions of editing and ordering, which Etter impressed was far more necessary than many people would often think – the order of poems, whether in a collection, magazine, or anthology, affects how, and whether they are read. Don’t, she said, start any publication with a twelve-page poem.

Etter and Patricia Debney, who was hosting, also talked about the form of the prose poem – a form in which Kent runs the only module in the country. Coming to a definition of poetry that focused on sensibility, rather than forming words into lines – they suggested that the difference between a lyric poem (including a prose poem) and prose was down to whether you were interested in telling a story or in investigating ideas – which, they agreed, was the work of the lyric poem.