In what was one of our highest tech readings so far, Amy Cutler provided an excitingly interdisciplinary event, applying poetic techniques of collage and erasure to film, text, diagrams and graphs: most frequently, though not exclusively, putting the disciplines of geography (her PhD, in geography, was on the coast and forest in modern British poetry) the philosophy of memory, an interest in materiality and in gender in conjunction through her practice. The result is a poetry that is intelligent and thoughtful about its own processes, with an impressive sense of scope – every project was different, employed different media and processes, – and an accompanying sense of depth. These works, both individually and taken together, are focussed and important, providing different ways of investigating, for example , and this was the thread that ran clearest for me through the work , the processes of memory.

Cutler’s first piece was a film and text montage that put pressure on the gendered subtext running through her source material, and the language of memory: –she said, of the French films she was using: ‘the hunt for memory in these clichés is also a hunt for a woman, recherche femme, the woman for whom Ridder becomes the subject of a time loop experiment in Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968), for whom the man journeys back to the still image of his own death in Marker’s La Jetée (1962), and for whom X dreams of Marienbad’. ‘Toast’, which Cutler read later, published in Litmus magazine, also focused its interests on the clichés of romantic memory and in aphasia, the speech condition in which impedes your ability to select the right word:

Language leaks through various holes in the skull / who’d have thought

we’d still be trying to be faithful/any of us can live on if we try / let’s say

any one of us / with one drink left on the late edges of a very cold night

Another poem, ‘Chanson’, riffed on two lines by Jacques Brel: Cutler explaining an interest in memory paradoxes through the words ‘I’ll never forget you’: which, whilst true when said in the moment of saying, has its truth invalidated by later loss of memory.

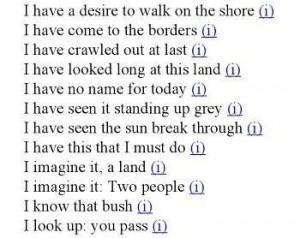

Next, Cutler read from an erasure poem: an erasure of the index of first lines of R S Thomas’s Later Poems. She was inspired, she said, by finding what she felt was a brilliant few lines of poetry:

on reading the index. The idea, she said, was to ‘make a love affair’ from them – to develop a love story out of the quite often religious texts of Thomas and of his love affair with the landscape of Wales, a love affair that talked to the idea, and this is why the later poems were used, was concerned with memory, with looking back at the end of life.

R. S. Thomas’s actual poetry, of course, is the antithesis of the sort of process-based practice that Culter puts his words through – which is part of the fun of it – she was interested, she said, in the strange figure that gets constructed in his poems which isn’t there in his poems – the way a different kind of poetic can emerge, by happenstance, out of what most people would regard as the material around his work, rather than the work itself. She enjoyed, too, the way in which the internal logic of the generic form she had chosen to inhabit, the index, created the movement of tone in the poem – which changes according to the alphabet – particularly, for example, around the letter ‘I’.

The materiality of the book, and its paratexts – marginalia and appendices, is of particular interest to Cutler, both in her research and in her marginal remarks around the readings of her poems. She talked about sharing experiences of making books as children, about her clear memory of the first time she ever encountered a footnote (-in the Moomins – it told her that if she didn’t understand a particular part of the story, she should get an adult to explain it to her. As no adult could offer an explanation beyond the understanding she had of the text – as she had fully understood it – this footnote created for her the sense of there being inaccessible knowledge that she was denied access to). This interest in paratext provides the form for an exhibition Cutler is curating in Leeds in June, called, Forest Expectation Sites, in which a series of artists and poets will create responses to the work of the poet Peter Larkin, creating a contemporary and artistic collections of adversaria, a Renaissance term for scholars’ annotations.

Cutler then read a collaborative piece that had been written in 2014 for the Polish Cultural Institute in protest against the fact that polish bishops had recently announced that all mothers should breastfeed, and that there was no way of distinguishing between sex or gender in Polish. Taking a polish instruction manual for breastfeeding, she and her co-translator translated and retranslated until the text started to deconstruct and critique itself, often in very amusing ways.

Again showing an interest in the relationships between languages, and in cultural memory in the guise of fairy-tale, Cutler read a poem of names for Rumpelstiltskin . The tale exists in many different European countries, but Rumpelstiltskin, whose power resided in his refusal to tell his name, is called by a different name in every language – not just a different name, but names with entirely different etymologies and meanings.

I’ll go with Shortribs, Sheepshanks, or Laceleg: a poor girl’s milling tune. I think

I’ve forgotten him now. Dear, it’s not possible to kill off anything in rumpled words

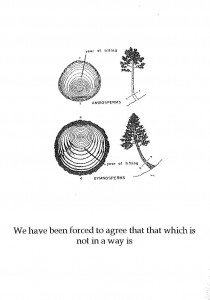

The latter part of the reading was more obviously concerned with Culter’s interest in geographical science and in the potentials of interdisciplinarity. Talking about Douglas Oliver’s diagram poems, she said diagrams (and this offers really interesting potential for understanding how her interest in translation relates to her other interests) are ‘machines of translation’, they enable you to move between disciplines, to create new thought. What is also important in this creation of new thought, is the bringing together of different media, creating new ways in which they communicate with and inflect off one another – Land Diagrams, an online series, curated by Cutler, in which writers respond the same visual encodings of landscape, is one example of this, and it is the crucial operation of her chapbook Nostalgia Forest (which she closed her reading with), from Oystercatcher Press in which dendrochronological (tree-ring reading) diagrams are put against fragments of Paul Ricoeur’s Memory, History, Forgetting (2000).

Here the interplay between the diagrams displaying how the history of a tree can be read from its physical form – rings, scars, incline – and a text on the functions of human memory poses questions about the materiality of memory, how the past is experienced in the present. Both diagrams and text are ‘found’ materials – it is in the moving between that new thought is created.