Professor David Stirrup (Kent) and Dr Jack Davy (UEA)

Principal Investigator and Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

At ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ one of the key themes of our research has been to examine the ways in which Native North American peoples have been displayed and interpreted in the UK, usually by people and institutions with no links to their communities and no established rights to speak on their behalf. Previous posts here have examined early twentieth century British performers adopting Native identities and their modern hobbyist equivalents, often dubbed pretendians. There has also been an intersection of this problematic representation at the juncture of celebrity culture and the museum space, and this blog highlights a recent example, which perfectly illustrates the problem.

There is a curious insensitivity within celebrity culture to the question of cultural appropriation. One of its regular manifestations is the image of a pop, or fashion, or film star of one stripe or another in a ‘Native American headdress’. From Cher to Jamiroquai, Pharrell Williams to Karlie Kloss, its ubiquity is increasingly being challenged by the voice and presence of Indigenous commentators and critics, who are steadily changing the public discourse around such behaviour. Among them, Cherokee scholar-activist Adrienne Keene and Anishinaabe fashion scholar and businesswoman Jessica Metcalfe are forthright in their condemnation of the reduction of ceremonial regalia to pulp-fashion:

[The fashion] takes something thought that is considered incredibly sacred and important and powerful in communities, and really trivializes that and attempts to take away its power by saying that it’s something that anyone can have access to and anyone can walk around and wear at any time.

For many years fake war bonnets have been among the headgear of choice for wannabes (both wannabe-celebrities and pretendians) at festivals, an extension of that celebrity culture. As one BtS interviewee, Sierra Tasi Baker (Kwakwaka’wakw), told us about her experiences of performing at festivals in the UK:

There’s a lot of people who wear Native headdresses, and a lot of people who wear tribal makeup, and a lot of people who are wearing our culture as costumes… and it’s just fancy dress to them… But it’s just so frustrating because when you wear Native headdresses or you consider a culture as just like fun fancy dress, it’s literally the same thing as black face, and that isn’t really coming across yet…

This conversation appeared to be shifting in tone in 2015, when the Glastonbury festival announced a ban on the sale of Plains-style war bonnets on the festival site. It was one of several festival bans that seemed to signal a growing understanding of the implications of such ‘redface’ activities.

This is a conversation we on the BtS team have individually had time and time again, but in the midst of conversations about decolonising curricula and museum spaces, we have definitely discerned a will to listen more to the voices of those cultural insiders who articulate the harm such images do—and Tasi Baker notes that while “there isn’t really this knowledge or this movement yet [in the UK] to address” such practices “people are really receptive when I have talked to them”.

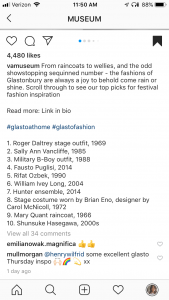

Earlier this month, the V&A made this post on their Instagram account (left). It read “From raincoats to wellies, and the odd showstopping sequinned number – the fashions of Glastonbury are always a joy to behold come rain or shine. Scroll through to see our top picks for festival fashion inspiration.” Item No.1, “Roger Daltrey’s stage outfit, 1969” turns out to be a classic example of the very thing we describe at the top of this item. Not a headdress, nevertheless, the buckskin leggings and fringed jacket with a beaded design (below) is very recognisably ‘Native American’ – generically non-specific, but unmistakable.

Regardless of its provenance, or Daltrey’s reasons for wearing it, the post is problematic for the way it both endorses this kind of celebrity dress-up (referencing an item in its collection that one would hope, in the present moment, would carry some kind of explanation as to that problematic nature) and invites its followers to mimic it as some kind of legitimate festival get-up. The V&A, as a cultural leader in the UK and the national museum of design and fashion, should be fully aware of the problematic nature of a dress-up costume like this and far more sensitive to the hurt that i

ts careless deployment on social media can cause. We recommend, here and elsewhere, better training on Indigenous sensitivities for museum social media teams to prevent this kind of oversight in the future.

Writing (tirelessly – all kudos to her for her patience) for the umpteenth time about Hallowe’en costumes, Adrienne Keene writes on her Native Appropriations blog: “Just stay away from the racialized costumes. It’s pretty simple. There are like ten-thousand-million other things for you to dress up as.” The same, needless to say, is true of festivals. And ought by now to be understood by museums. “My culture,” Keene observes quite simply, “is not a costume.”