Dr Jack Davy (University of East Anglia)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

In the previous post for this blog David Stirrup discussed the broad sweep of “Beyond the Spectacle”; the wide goals and ambitions of the project as it seeks to engage with Native American presence and influences in Britain. This post continues this thought by examining the methods by which we as researchers can develop an understanding of these Native American engagements with the British public.

As with any research programme of this nature, and as David identified last week, often the best place to encounter those historical engagements is through newspaper reporting. Over the last few weeks I have been using news database tools to identify Native presences in the British press archives, and in this post I am going to tell you one story in particular which presents an invaluable window into the British relationship with Native Americans in the first decade of the twentieth century.

The story is on its face absurd and thus it appears to be funny. That is how the press treated it, apparently how the courts saw it at the time and I’m sure, how many readers will interpret it at first glance. It is how I reacted when I saw the headline. But it isn’t funny at all. It is tragic. It is the story of the Hunt for White Cloud.

In 1905 an entrepreneur named F. B. Burton established a visitor attraction at Earl’s Court which he called the “Indian Village”. A transparent attempt to replicate the hugely successful Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, which had featured at the venue in 1887 and 1902 to huge crowds. Burton assembled an encampment of tipis and populated them with “authentic Indians” – he went to court to justify his employment of five “Red Indian” children at the village, apparently brought to Britain under unclear circumstances solely for this purpose.

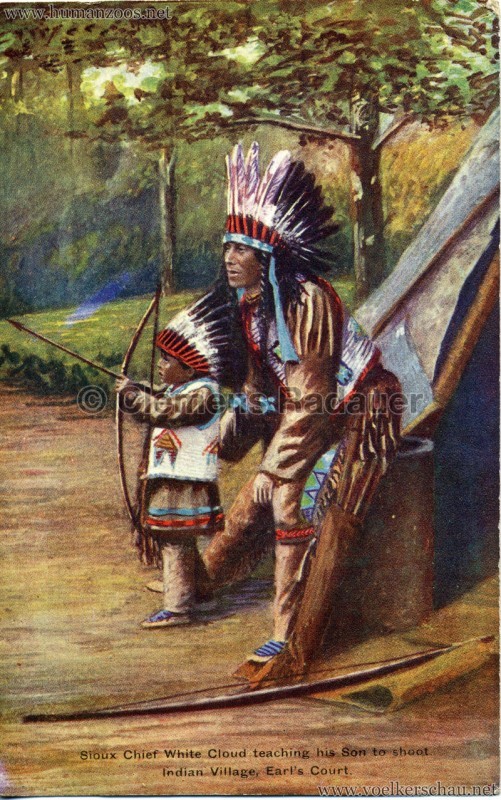

One of his performers was a man named White Cloud, advertised as a “Champion archer” and a “Sioux”, apparently travelling with his “son”, possibly one of the children Burton imported. A publicity postcard shows White Cloud teaching his “son” to shoot a bow, both dressed in full chiefly regalia, including beaded buckskin shirts and feathered war bonnets. The performer, a lawyer later recalled in court to much hilarity, “called himself the “White Cloud” because he was dark”. In 1906 the show broke up, and this is where our story begins.

In mid-1906, White Cloud disappeared. Reports were that he had returned to New York ahead of legal action, and the following year a manhunt was launched, with advertisements seeking him on both sides of the Atlantic. The reason: White Cloud was named as a respondent in the Green divorce, a court proceeding which scandalised the London and regional papers through 1908 and 1909. White Cloud had, it appears, been conducting an affair with Emily Green, wife of the celebrated English professional stage strongman John Groom Marx, the Modern Hercules. Emily had, the papers recounted, deserted her husband and three children to run away with White Cloud and become the human target in his famed archery display.

This is where most coverage ends, and it is an attractive story, the notion of a woman pulled by love between two stage celebrities, abandoning her family for the passionate embrace of a “savage man” from the edge of Empire, only to be deserted herself and forced to enter the Lambeth Workhouse in destitution. It was a morality play, a caution to other wives who might stray and a commentary on the “savage lusts” of the non-White races. Marx (real name John Green), was granted his divorce and full custody of the children. Court reports portray him as attractive and popular, eliciting laughter from the gallery at his testimony on the troublesome nature of women, while Emily is illustrated as barely literate and untrustworthy.

But more detailed reports recount what he actually says. For while Green denies many of the charges laid against him, the testimony is a litany of vicious domestic violence and unfaithfulness to his wife and family. The Greens were married in 1894 and for a decade were ostensibly happy, until John began drinking heavily. In court Emily produced scars from beatings and told of her husband’s affairs with waitresses and saloon madams; John even acknowledged breaking her nose, although he claimed it was justified as she had stayed out too late, an excuse apparently accepted by the court. He had a string of convictions for violence, including a memorable arrest for brawling with an unknown party at the London Aquarium. None of it mattered, because Emily had done the unthinkable; she had been “found in bed” with a “Red Indian”, and worst of all publically claimed not only to be White Cloud’s wife, but, falsely, an Indian herself. The implication underlying all of the testimony and reporting is that she betrayed not only her family, but her race. Emily was ruined and, it appears, disappears from the historical record herself at this point.

The question now is how we, as historians, address this tragic story. The first goal is to try and achieve what the lawyers of 1907 conspicuously failed to do; to find White Cloud. We have access to resources they could not reach; census records and school enrolments, oral histories and published accounts. We have to dig down to locate not only White Cloud but also Burton, to uncover the nature of their financial relationship, the companions alongside whom he performed and the audiences to which he displayed his archery talents.

Because White Cloud may not be White Cloud. Like the Iron Tail of a later generation, he may be nothing more than a charlatan, a White American or European playing at dress up, creating an ethnodrama for audiences, cashing in on the cultural and historical heritage of other people; he would hardly be the first or last to do so. So we must also explore theatrical records and contracts, searching for archery specialists of the era to try and determine whether the mysterious White Cloud was really who he claimed to be.

By pursuing this research we can generate a picture of the transatlantic context of the Green v. Green divorce and the public sideshow which accompanied it. We can explore the racism inherent in the judgement which destroyed Emily Green’s already shattered life and by doing so get to the heart of the complex historical trajectories which connect the British public and Native American communities and their shared, often controversial racial histories which form the central focus of this AHRC research project.