Dr Kate Rennard (Kent) and Dr Jack Davy (UEA)

Research Associates, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

Standing in front of the audience at BBC MediaCity on 29 August 2018, Chief Bill Cranmer of the ‘Namgis First Nation in British Columbia talked animatedly about the importance of the Salford Totem Pole, soon to be re-erected nearby through the efforts of Stephen Coen (of Salford City Council) and Fortis Construction. The totem pole was carved by Bill’s elder brother Doug, a master carver of the ‘Namgis Kwakwaka’wakw people, in 1968 for Manchester Liners, as a symbol of the trade links between Canada and the city. Chief Cranmer spoke of the pole’s significance to Salford and also to the ‘Namgis nation. The pole tells the histories of the ‘Namgis people through its figures and its very existence also stands as testament to the continued cultural survival and revival of Canadian First Nations, despite the government’s historic efforts to erase their cultures and assimilate their peoples in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For Bill Cranmer, the Salford Pole represents not only the past of the ‘Namgis people but also their continued presence.

This attitude stands in stark contrast to the narrative presented to the British public by the Guardian and the Daily Mail, on 20 September, when both newspapers published photo galleries of Edward Curtis’s images of Native North Americans from the early twentieth century. These images are presented with little context, in particular without mention of the deliberate dishonesty that lay behind so much of Curtis’s published work or acknowledging their troubled relationship with the thriving contemporary existence of Indigenous peoples in North America. In the Guardian’s gallery, for example, all a reader is given is a brief commentary, by photo editor Paul Bellsham, that this is a “stunning record of vanishing Native American tribes” that is currently up for auction. Some people might ask the significance of our concern, and ask “So what?”, to wonder why it matters that the newspapers didn’t give any background information. But a full explanation matters because here context is important. This omission hides not only the violence and loss inflicted on Indigenous North American peoples by colonial governments as they outlawed the very items and ways of life Curtis supposedly sought to capture, but also obscures these nations’ continued survival and their own responses to these images.

Source.

Curtis’s work was ground-breaking in early twentieth century photography – he travelled across North America taking high-quality photographs of people in ostensibly traditional Native dress performing ostensibly traditional Native ceremony for sale as photobooks. He did so as part of a project launched by the financier J. P. Morgan, seeking to turn a profit from the widespread concern that Native American tribal nations would soon have been exterminated; that this was the last chance to record traditional Native life. He visited many nations, and among the most significant of those featured in the Guardian are of the Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, including the ‘Namgis nation. But despite Curtis’s predictions, these communities have not vanished; indeed, as Chief Bill Cranmer attested, they are thriving. To ignore their existence in the context of Curtis’ work as the Guardian and Daily Mail did, does very real harm to the nations involved in these photographs. It perpetuates the widespread notion in Britain that there are no “real Indians” anymore – for more on this damaging idea, read our recent blog-post about the experiences of Kainai actor Eugene Brave Rock in London.

So what context should the reader be given to really understand these photographs?

Curtis’s project was hailed at the time and since as the last great record of Native American life before the supposedly inevitable march of Western civilisation swept it all away. His project tapped into the stereotypes of “Vanishing Indians” and “noble savages” made popular by such works as James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans. Not just literary device, this image was used to justify the imprisonment, murder and forced assimilation of Native nations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Although his intentions were paternalistic rather than deliberately destructive, Curtis’s images were a major part of this movement, appearing to capture the supposed disappearance of Native life as it happened. It’s clear that Curtis himself felt affection for his subjects and genuinely believed, in the manner of a colonial missionary or Indian Agent, that his actions helped them, while privately making money for himself. Whatever his intentions may have been however, it is important to acknowledge the work these photographs did in popularising the idea of “Vanishing Indians” and, in doing so, the real damage that it inflicted and continues to inflict on the Indigenous peoples in Canada and the U.S.

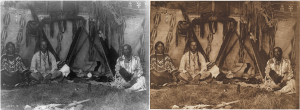

With context, it becomes clear that these photographs do not actually portray the “vanishing Native American tribes” that Curtis and others have claimed. Although the clothing and actions of his subjects bore resemblance to historic regalia and dances, by the time Curtis arrived they had been driven underground, often made illegal. In 1906, for example, he surveyed tribal nations of the Plains, showing men on horseback in dramatic feathered headdresses; he documented what he considered the pure, honest depiction of what he sought. Yet on reservations across the Great Plains, Native peoples were starving – so many had sold their regalia to feed their families that Curtis was forced to carry trunks full of costumes for his subjects to wear. Curtis also made sure to erase evidence that Native peoples were successfully incorporating modern conveniences into their lifestyles, in order to avoid any suggestion that they were not actually vanishing but rather adapting to survive. For example, telegraph wires in evidence in the original negatives disappeared from the final prints. In perhaps the most famous example, the image titled “Lodge Interior – Piegan” that is featured in the Guardian, a clock was removed from the final edit.

Some of the images in the Guardian and Daily Mail pieces feature the dramatically posed masked dancers of the Northwest Coast, but these in particular are not what they seem. These photographs were all taken in 1914 at a Kwakwaka’wakw (then spelled Kwakiutl) community off the coast of Vancouver Island. Curtis transported not only his camera equipment, but an entire film crew to this then remote spot to capture images of what he considered “authentic” Kwakwaka’wakw dancers; preparations for the filming took him three years. When he arrived however, Curtis found that what he needed was nowhere to be seen. There were few surviving totem poles, none of the great longhouses and no masks or regalia on display. This was, in part, because few Kwakwaka’wakw still lived in the town. Most had moved to Alert Bay, a nearby cannery town established in the 1880s to concentrate the Kwakwaka’wakw communities of British Columbia, decimated by small pox two decades earlier, onto one island. The community there was a model town, built on modern lines and without traditional structures; older villages, like the one at which Curtis intended to film, were already crumbling back into the forest.

Additionally, laws introduced in 1884 had made traditional masked dancing illegal. These laws were frequently ignored and patchily enforced at this time, but open displays of regalia or large congregations of people could attract fines and prison sentences if noticed by the authorities – in inviting people to demonstrate their regalia and perform publicly in the manner displayed in his photographs, Curtis exposed the community to serious legal consequences. Seven years later, a major ceremony hosted by Chief Dan Cranmer, Chief Bill Cranmer’s father, was the catalyst for severe reprisals by Agent William Halliday and the Indian police, leading to more than 40 arrests and the deliberate confiscation, desecration and illegal sale of their regalia and ceremonial items. More than twenty people were imprisoned for refusing to co-operate with the authorities and deliberately humiliated by forced manual labour. A residential school was built at Alert Bay to which most Indigenous children in the region were forcibly incarcerated, tortured and abused simply for being Native. Its explicit mission was to “kill the Indian” in the children. The Kwakwaka’wakw peoples therefore faced violent consequences for continuing to practice the cultural traditions Curtis wanted to publicise.

As with the Plains photographs, Curtis therefore sought to recreate the images he wanted, ordering prop house fronts and poles to be erected as quickly as possible. He handed out cedar bark capes and wooden clubs to participants and eventually persuaded mask owners to bring out their sacred masks and regalia. He even made the men shave off their traditional luxuriant moustaches in the mistaken belief that they were a modern affectation. Curtis then presented the community with a melodramatic script he had written and made the performers enact made up movements at his direction, telling a love story set between two warring tribal factions. Disturbingly, he managed to persuade one man to enter a gravehouse, disturb the skeletons there, and even perform a dance wearing several skulls as a necklace. His final product, a motion picture named In the Land of the Headhunters, was a commercial flop. However, it has often, like his photographs, been praised for its seemingly “authentic” portrayal of “Vanishing Indians.” Despite its manufactured content; in 1999 it was added to the US Library of Congress’ National Film Registry of particularly important film works – as a documentary.

Curtis’ photographs are undeniably spectacular. But, as the ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ project aims to show, it is important that we invite an audience look beyond that. The collection featured in the Guardian and Daily Mail needs to be presented in context, for what on the surface seem to be portrayals of “vanishing Native American tribes” are instead a tacit celebration of the assumption that settler colonial societies had destroyed Native cultures. Yet these images represent not only the violence and losses these policies inflicted on Native peoples, the effects of which are still felt today, but also their ultimate failure. As evident in previous blog posts here, Native peoples have and continue to demonstrate the vibrancy and variety of their surviving artistic and social lives, and to fight against the injustices of the past. For example, the regalia Halliday stole in 1921 has almost all been recovered by the ‘Namgis people. The Salford Totem Pole, along with others from Kwakwaka’wakw carvers that are located in Britain, stands as a powerful symbol of this resurgence of Native peoples in the face of colonialism. It also represents the lengthy and ongoing struggle they face to repair the damage done to their nations by the assimilationist policies embodied in Curtis’s images, as they move forward into an Indigenous future.

A must read. The background of Curtis’ images deserves to be common knowledge. Thank you for this. I always look forward to the posts on here.