Professor Jacqueline Fear-Segal (UEA)

Co-Investigator, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

The oral history programme of ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ is a vital component of this project. We anticipate it will enable the inclusion of a wide range of Native North American views and voices. With the 20th and 21st centuries being our main focus, these voices will include those of current Indigenous visitors, as well as those who have returned home. In some instances, where appropriate, we also plan to interview non-Native people who have devoted much their time to working with and facilitating Indigenous causes in Britain. Much of Native presence in Britain has gone unnoticed, been rendered invisible, or staged as spectacle. It is hoped that oral histories will provide an opportunity for a range of Native peoples to contribute directly to this project by giving their responses to visiting Britain in their own words.

During the first eight months of this project, the research team’s focus has been on locating the written materials available in archives in Britain that document the many journeys of advocacy and diplomacy, as well as cultural and political exchanges which have taken place down the years. We are aware that this record is almost invariably written from the perspective of those holding positions of power in Britain. Occasionally, snatches of Native comments or observations are reported, but generally these are contextualised within a British frame. In the early days, when many Native visitors did not speak English, their reported words were also refracted through translation. As we saw in a previous blog post on “Buffalo Bill’s ‘Lakota’ Indians” (27 November 2017), the Lakota leader Red Shirt responded very frankly to a question about his people’s future. He told the journalist that, back on the reservation, the Lakota were all starving because their land had been taken and the buffalo on which they totally depended had been destroyed. But his remarks were placed within the wider frame of an article that presented a narrative of the “vanishing Indian” and the exoticism of “savagery”. However, here as elsewhere, with skill and sensitivity historians can read against the grain of the archive and enable Native voices, in historian Daniel K. Richter’s words, “to speak through the filters of European documentation”.

Although for many professional western historians written records have been and remain dominant, since the mid-twentieth century a new credence has begun to be given to oral sources. This was driven in part by a new interest in “history from the bottom up” and the growing desire to include and understand large segments of the population previously ignored in historical studies and absent from the documentary evidence –working classes, minorities, children, women, the poor, the old, the illiterate, and an increasing number of other overlooked groups. In order to hear the views of these groups, oral testimony started to be incorporated into historical studies. In Britain, this gathering of momentum among different groups led to the founding of the Oral History Journal, by Paul Thompson in 1969, closely followed by the establishment of the Oral History Society, in 1973. Similar developments were taking place in the USA, where the Oral History Association was organised.

For Native peoples, a deep respect for oral histories has always been indivisible from cultural traditions. While many of the practices that supported such traditional spoken transmissions have been disrupted by missionary and government determination to undermine Native societies, particularly in the boarding/residential schools, appreciation of orality and the importance of stories has survived. Leaders have fought hard to have oral histories recognised; the late Vine Deloria Jr. campaigned to have oral evidence recognised in the court system. Integral to the worth accorded the stories is an appreciation of the importance of who is allowed to tell them and how they are told. As the Kiowa novelist, poet, and Pulitzer Prize winner, N. Scott Momaday reminds us, “In the oral tradition silence is the sanctuary of sound.”

In the past, there have been moments of deep controversy when Native people, working with non-Native anthropologists and other investigators, have unsuspectingly been used as informants to divulge sacred knowledge or information that should remain confidential. Our heartfelt intention in this project is to involve all Native interviewees and interviewers as research collaborators who will contribute to the shaping as well as to the findings of the project. The interviews conducted on behalf of the project will be made in the spirit of creating an archive that will be fully accessible.

We invite a wide range of people to contribute to the oral history strand of ‘Beyond the Spectacle’. Whether Native artists, diplomats, performers, academics, military personnel, students, or activists, each of their respective decisions to travel to the UK represents an aspect of the complex and entangled motivations that have characterised Indigenous visits down the centuries. The thoughts and responses of all these visitors will contribute to our understanding of contemporary Native North American presence in Britain to help us see beyond the racist and romantic conceptions of “Indians” and reveal the more complex realities of contemporary Native American experience.

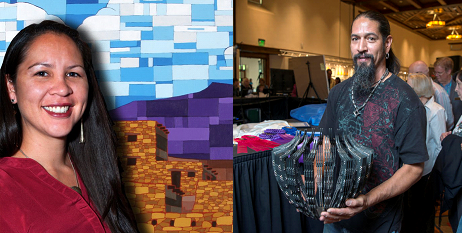

Left: Marla Allison (Laguna Pueblo) will be in residence for ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ at Rainmaker Gallery, 11 May 11-7 June 2018.

Right: Pat Pruitt (Laguna Pueblo & Chiricahua Apache) won the Best of Show award at the 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market with this zirconium and titanium sculpture.

Marla and Pat will both contribute to the project symposium, on 6 June 2018 – tickets still available.

All members of the ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ research team are trained and practised oral historians, and we have also recently recruited two trainee UEA student oral historians to assist with this strand of the project: Rhyannon Brignell and Kaitlyn Neve. Rhy and Kaitlyn will attend the Oral History Society “Introduction to Oral History” course at the end of April (funded by the School of Art, Media, and American Studies, UEA) and then will work with members of the team to hone their new skills – please read their personal introductions below.

I want to end this blog post with a request for your help and involvement. If you know of anyone who has a connection to any Native North Americans who have visited Britain, then please let us know. And if you become aware of any planned Native visits, then again, please get in touch: beyondthespectacle@kent.ac.uk

OUR TRAINEE STUDENT ORAL HISTORIANS

Rhyannon Brignell (UEA)

My name is Rhy Brignell and I am a first-year PhD student of American Studies at UEA, studying the relationship between Native American literature and the extractive industries. I have always been interested in studying the United States through alternative narratives. During my undergraduate degree, I deliberately selected comparative modules in Cuban, Australian, and Transpacific literatures. Then, in my Master’s year, I turned to Native American studies, taking classes in Native literature and theory, and Prof. Fear-Segal’s module on Native American history. My Ph.D dissertation is focused on the experiences of the Osage during the oil boom of the first three decades of the twentieth century, with particular attention paid to four novels: Sundown by John Joseph Mathews, Mean Spirit by Linda Hogan, A Pipe for February by Charles H. Red Corn, and The Osage Rose by Tom Holm. I am also keenly interested in the intersection between Indigenous cosmopolitics and the energy humanities, which I am formulating through an analysis of oil culture and petroviolence on the Osage reservation in the early twentieth century.

The oral history training will be very useful to my own research, because I am intending to make a research trip to Oklahoma, which will involve recording oral histories. By collaborating with ‘Beyond the Spectacle’, I hope to gain the skills required to conduct interviews and record oral histories ethically, and I hope to apply these skills to both my own research and to research for ‘Beyond the Spectacle’. More generally, I am keen to bring indigenous voices to the forefront of multi-disciplinary academic research and beyond, and I am excited to be a part of such a far-reaching and impactful project.

Kaitlyn Neve (UEA)

My name is Kaitlyn and I am a second-year undergraduate at the University of East Anglia. My interests have varied since attending UEA, but non-western art and anthropology has captivated me from the beginning. My main focus has been Oceanic art and anthropology; wherever possible I make sure to incorporate an object or artist from this part of the world in my work. However, I have thoroughly enjoyed learning about the Americas, Africa, and India too. One essay I wrote allowed me to show how the function of a totem pole, made by the Kwakwaka’wakw, has changed over time. This research led me to enrol for a module in the following year, studying the National Museum of American Indians and the NAGPRA act. My interest in this area heightened as I further researched colonialism and its repercussions the world over. I felt my reading was weighted towards one side of the story; for the majority, I could only find accounts written by colonialists. In my essays, I have often questioned how academics interpret written records during the colonial era. This is something I am passionate about researching further; we shouldn’t be taking these written accounts as truths, but rather we should evaluate all elements of the historical record to gain a better understanding of the events. I was drawn to ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ for this very reason. The team is working to listen to the voices of people who have often been silenced, so that their perspective and views can be included in the historical accounts.

I hope to transfer the oral history skills obtained through working with the Beyond the Spectacle team into my current degree work, and then also into my Master’s degree. For this, I hope to focus on representations of indigenous groups within the western world. I would like to look into how the function of objects may have changed with the arrival of colonialism, and then again with the advent of decolonisation. If possible, I would also like to discuss how objects created by Indigenous groups are being displayed in museums, and whether these communities are able to contribute to how their culture is exhibited. Although it is most common to study the effects of colonialism on Indigenous groups in the location where these groups originated, the relationship of Britain to North American is very long-standing. So it is important to also consult how their history is being represented here, and whether they have any say in how their story is being told.

There is a lot of work that still needs to be done in this area. I am proud to be working alongside the team in this project, because I truly believe that what they are doing is vital to the Native American communities and to Britain. I hope to help make these connections more widely known here in the UK and to break down the deep-rooted stereotypes that are still current today.