Dr Padraig Kirwan (Goldsmiths, University of London)

Board Member, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

In light of news of recent fundraising in Ireland for the Covid-struck Navajo Nation, which has drawn comparisons in the Press with “The Gift”, we asked our colleague and friend Padraig Kirwan to share a little of his and his Choctaw collaborator LeAnne Howe’s work on that 1847 act of transatlantic compassion.

Since 2015 I have had the good fortune to have spent a considerable amount of my time researching the circumstances and enduring legacy of the remarkable donation of $710 (or possibly $170) to Ireland’s starving poor during the Gorta Mór, or Great Famine. The money was gathered by members of the tribe in a town that is today known as Skullyville — a name which is, appositely enough, derived from a Choctaw word for ‘money’, iskuli — this particular gift has long endured in the minds of both the Irish and the Choctaws. Above all others, this is certainly the single most well-known donation sent to Ireland. It continues to be so despite the fact that countless donations were made to New York’s General Irish Relief Committee during the famine (1845-49). It is not difficult to see why the tribe’s munificence often continues to outshine the benevolence of other, often wealthier, parties; contributions sent by bankers and merchants such as Lionel de Rothschild, who was a leading figure in the British Relief Association, can hardly be expected to stir the emotions in quite the same way as the story of the Choctaw tribe’s generosity does. Likewise, regardless of whether or not Queen Victoria fully deserved the moniker ‘the Famine Queen’ — the insulting pet name assigned to her in Ireland after the apocryphal rumour that she donated £5 to help the starving Irish was widely disseminated — it is not entirely surprising that the Irish singularly failed to celebrate the arrival of the monarch’s money. What may strike some as curious, however, is the fact that the tale of the $170 greatly eclipsed that of several other truly incredible acts of kindness; Christine Kineally has shown that money was sent by those recently enslaved in the Caribbean and from a prison ship in Woolwich, London, as well as pauper orphanages in New York. Indeed, she points out that the outpouring of support for the Irish ‘cut across religious, ethnic, social and gender distinctions, with donations coming from as far away as Australia, China, India and South America.’ The depth of compassion shown through those moments of generosity and selflessness is astonishing, for sure. In Ireland we have always recognized the debt that we owe to many of the world’s most vulnerable communities, regardless of whether or not a direct link was forged between our peoples during the famine years; that someone thought of us then is enough to remind us that we must always think of others. Although this is the case, it is surely fair to say that the Choctaw contribution is the one that is both remembered most vividly. That gift is thought vital not only to the survival of Ireland’s starving masses in 1847; it is also reckoned to be a central narrative strand in the long story that reflects both the history of the nation as well as Irish cultural mores, traditions and values.

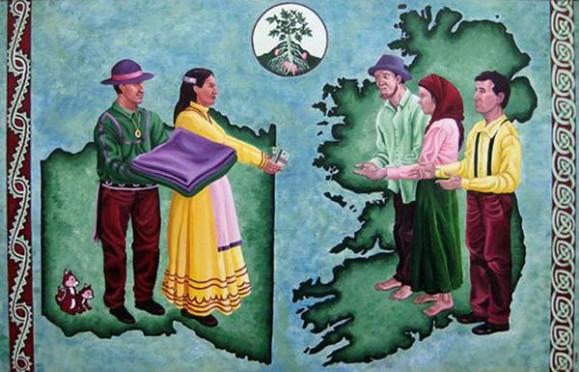

A huge part of the good fortune mentioned above arises from the fact that I have spent many hours in the company of Choctaw writer and scholar LeAnne Howe while examining the gift. As co-editors of Famine Pots: The Choctaw-Irish Gift Exchange 1847-Present, we came together with fellow Choctaw and Irish contributors in order to think more deeply about the gift’s significance and multilayered meanings, both then and now. In considering the circumstances which may have informed the impulse shown by those tribal members who decided to help the starving Irish we have considered multiple points of connection between our two communities. Recently dislocated and violently removed from their ancestral lands, the Choctaw surely had a deep empathy for what tenant farmers were experiencing in Ireland during a time of mass eviction. Faced with the twin spectres of death and the destruction of community, both peoples were also grappling with other decimating forms of trauma too. These ranged from the loss of language to an increased alienation from spiritual traditions in some form; much as the tribe had to adapt their practices in the wake of their newfound distance from sacred sites such as their mother mound at Nanih Waiya, the site which represents their birth as a people. Many amongst the Irish population were increasingly distant from “old Gaelic culture” (David W. Miller). It is unlikely that all of these similarities were mentioned at the meeting held on March 23, 1847 at the Agency Building in Skullyville, but it is very likely that the Choctaw gathered there interpreted the news from Ireland through the lens of their own recent experiences. There are plenty of other, happier and more empowering, correlations too, of course. Although confronted by an array of hardships that the 1830 Indian Removal Act both increased and deepened, by 1847 the Choctaw had shown amazing fortitude in surviving forced migration from Mississippi to Indian Territory (what is Oklahoma today). By banding together ever more tightly and displaying a steadfast resolve in the face of President Andrew Jackson’s genocidal policies, the tribe had proven a great deal about continuance and strength, both to the U.S. government and the world. In choosing to send relief to a starving community thousands of miles away they underscored their sovereignty as a people; having adopted their own Constitution in 1838, many citizens of the Choctaw Nation may have recognized that this act of nation-to-nation giving might carry a forceful message about continuance and autonomy. It may even be the case that certain members of the tribe heard stories of ancient Celtic mythology, ring forts and a complex indigenous legal system called the Brehon Laws, and identified with of the tales that Irish immigrants brought to the United States. Above all, and most importantly, those who gave both honoured and continued age-old belief systems about giving. LeAnne says that Choctaws are givers. “The Mississippi Provincial Archives [1701-1763]: French Dominion, are replete with instances of the Choctaws giving food and shelter to neighbouring tribes. They even gave food to the French colonizers that were settling in their midst, she said.”

Perhaps counter intuitively, this tradition of giving may explain — at least in part — why it seems to be the case that the donation has not been referred to in Oklahoma as often as it has been in Ireland. It may well be that the tribe took store of all of the inferences laid out above, but that the act of giving was not deemed entirely remarkable in and of itself. This may help to explain when several Choctaw contributors to Famine Pots remember hearing passing references to the gift rather than fully fleshed out stories. As such, it seems that this story garnered little enough attention prior to the trip that Irish writer and humanist Don Mullan took to Oklahoma in 1989. One contributor to Famine Pots, Choctaw historian Jacki Rand, explains that before then “the Choctaws had not retained a collective memory of the gift.” For that reason, one can’t help but wonder if this is possibly because an act of selflessness that many observers find remarkable in today’s world was, in fact, a staple and a given amongst those who gave so readily to the starving people of Ireland in 1847.

Consider what the Choctaws did in 2018, said Howe. “Once again the Choctaw Nation came to the aid of another nation; this time it was the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota. When Dakotas protested the Dakota Access Pipeline, thousands of Natives across the United States came to their rescue, as well as indigenous people from around the world. The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma sent aid, and most importantly they sent tribal members to North Dakota. Choctaw citizen Cody Wilson and other tribal members bought firewood, sleeping bags, generators, propane heaters, tents, thousands of gallons of water, and other supplies in North Dakota stores to give to the Dakota people.”

Of course, it could also be argued that amongst the Irish this story of connectedness fell into abeyance somewhat too; Mullan’s sleuthing and gratitude brought a story that many of us had heard from primary school teachers and grandmothers to well-deserved national and international attention.

Today, the Irish have taken an American Indian tribe into their hearts. They have collected nearly two million dollars to give to the Navajo Nation, a people in need during this terrible global pandemic. That’s the spirit of true gift giving.

Philip Carroll Morgan says it best. “Let us celebrate our Choctaw-Irish friendship and shared hopes, but at the same time let us become more active in diminishing fear and greed, as well as more active in establishing compassion and friendship as shared central values.”

Famine Pots: The Choctaw–Irish Gift Exchange, 1847–Present, edited by Padraig Kirwan and LeAnne Howe, will be published by Michigan State University Press in October 2020.

Famine Pots: The Choctaw–Irish Gift Exchange, 1847–Present, edited by Padraig Kirwan and LeAnne Howe, will be published by Michigan State University Press in October 2020.