Professor David Stirrup (Kent)

Principal Investigator, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

Newspapers are inevitably a key resource for a project like ours, and it is perhaps needless to say that the British print media is littered with references to Native Americans. Much of that littering is just that – asinine, stereotypical, often racist. There is, however, a lot of interesting, observant commentary, as well as much that is simply curious.

One of our favourite moments, hinted at in the title of this piece, occurred in 1887, when a somewhat green Sporting Life journalist mistook Red Shirt, one of the most famous Oglala Lakota warriors to have set foot on British soil, for an “Ojibbeway.”[1] Let’s rewind, though, as this demands a little background. From the late 1830s through until the 1880s, there was a real preponderance of Anishinaabe – Ojibwe specifically – visitors to Britain. Beginning with Gakiiwegwonaby (Peter Jones) in 1837, these visitors generally came in two roles: firstly, like Jones, they came as preachers, Methodist missionaries raising money for the church back home.

Wednesday 18th.—In the morning breakfasted with a large party of Ministers, (Methodists and Dissenters,) at the Rev. J. Bunting’s. At their request I gave them an account of my interview with the King and Queen at Windsor. In the evening went to the Missionary meeting at Pitt Street, in my native costume.”

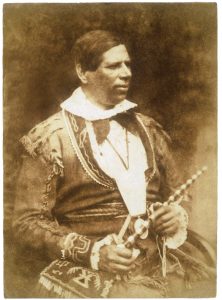

Gakiiwegwonaby (Peter Jones) in the final days of his first tour of Britain.

Secondly, although often the preachers combined these roles, they came as performers, providing “illustrations” of their manners and customs, and lectures on the same.

Besides Jones, then, we see: Gaagigegaabaw (George Copway, 1840s and 1850 en route to the Peace Congress in Frankfurt); Naaniibawikwe (Catherine Sutton, 1837 and 1859); a troupe of “Ojibbeway” who performed with Catlin (1843-44); a second troupe traveling under the leadership of Jones’s relative, Maungwudaus (George Henry, 1845-1848); as well as other groups of “Ojibbeway”—who may or may not be so—in the 1860s; and finally, later, the Reverend Henry Pahtahquahong Chase, who came to Britain in 1876, 1881, and 1885.[2]

“This, then, is a part of England. How crowded are the streets! What large truck horses! with plenty of omnibuses and noisy beggars; and worse than all, the shaving hack-drivers. Beardless as I am comparatively, they yet manage to shave me.”

Gaagigegaabaw (George Copway) on his first impressions of Liverpool in 1851

The crossover in these visits is particularly intriguing. Although he was effectively put on display, encouraged against his better judgement to dress in traditional “costume” to deliver his talks, Peter Jones is generally (correctly) treated as a man acting under his own agency. Maungwudaus’s troupe, however, when tragically beset by smallpox while in Brussels, left Catlin scratching his head as to the morality and practicality of displaying Indigenous performers. Their timelines in Britain cross over, and Maungwudaus was pretty well educated—like Jones. And yet where one was favoured as a “civilized” man of God with an albeit exotic heritage, the other, who performed that heritage more explicitly, was momentarily infantilised in the eyes of his “keeper”.[3] As Maungwudaus’s own observations of the society he encountered suggest, though, his was far from being a child’s view.

“Like mosquitoes in the summer season, so are the people in this city, in their numbers, and biting one another to get a living.”

Maungwudaus on his impressions of London, 1848.

The other intriguing element of this period in history, however, is the sheer ubiquity of the “Ojibbeway” not just materially but metaphorically. Scattered throughout the press, the term “Ojibbeway” becomes not just synonymous with but a replacement for “Indian”. As a result, we see a whole host of references that range from the pejorative to the downright derogatory. In the Leicester Chronicle January 3rd 1863, for instance, part one of a serialization on “The History of Leicester” situated its readers’ understanding of the Britonic tribes by noting that their habitations were “as little entitled to the appellation ‘towns,’ in the modern sense of the term, as the kraal of the Hottentot or the village of the Ojibbeway”. Still on the early side for the fully blown “Human Zoo,” nevertheless the author could probably have relied on some level of knowledge of his readership sparked by interest in the various visiting Ojibwe troupes, while interest in the Indigenous peoples of southern Africa had persisted since the display between 1810 and her death in 1815 of the Khoe-Sān woman Saartje Baartman, popularly known as the “Hottentot Venus.” Afterwards, British interests in Cape Colony and mounting tensions with the Boer kept South Africa in the news throughout the 19th century.

“The only fault we saw of them, are their too many unnecessary ceremonies while eating, such as, allow me Sir, or Mrs. to put this into your plate. If you please Sir, thank you, you are very kind Sir, or Mrs. can I have the pleasure of helping you?”

Maungwudaus on the English upper crust, 1848.

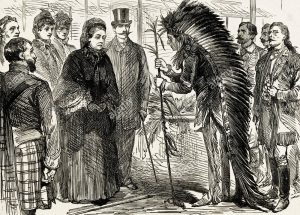

In that same year, 1863, there were also a number of newspaper articles tallying the various visits to the metropole by “strangers of little known and half-civilised nations” (The Standard August 5th 1863), suggesting a zeitgeist to which these allusions were directed—although as Maungwudaus’s words above suggest, it wasn’t only the strangers whose manners were under scrutiny. At the same time, there are more comical notes, such as the excited journalist who got the scoop for Sporting Life on Buffalo Bill’s arrival at Gravesend for the first Wild West show in the UK in 1887 (April 15th 1887). Mock-wearily boasting of his sprint through half of London’s docklands for the story, said journalist also proclaimed his interview with the renowned Lakota warrior Red Shirt, writing: “I had also the extreme felicity of a little quiet chat with “Red Shirt,” the great Ojibbeway (I think it’s Ojibbeway) chieftain…” Felicity indeed, except that Red Shirt had already achieved fame through Buffalo Bill’s proclamations of his standing as “second only to Buffalo Bill,” Hunkpapa Lakota leader at the Battle of Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn), where Custer was routed, in which Plains forces took on the Seventh Cavalry.[4] A modicum of fact checking would have confirmed for the reporter that the Ojibwe—a lakes and woodland people in the main—did not participate in that battle. More to the point, perhaps, he might also have learned that the Lakota and the Ojibwe were sworn enemies. At least, when a later journalist reported on Red Shirt’s visit with Gladstone, he not only knew who he was but captured his own words.

“The White Chief is not as the big men of our tribes. He wore no plumes and no decorations. He had none of his young men (warriors) with him, and only that I heard him talk he would have been to me as other white men. But my brother (Mr. Gladstone) came to see me in my wigwam as a friend, and I was glad… for though my tongue was tied, in his presence, my heart was full of friendship.”

Red Shirt, quoted in a syndicated news report, 1887.

The papers reveal many more quirks than the Sporting Life reporter’s error, of course. Whether it be the 1925 sculpture of the Prince of Wales dressed as a Plains warrior that was carved out of butter… or the brief article in the Sunday Tribune in 2003 that tells of Barnsley bricklayer Mick Henry’s discovery that his Canadian father was in fact “chief of the Ojibway,” leading to a long search that ended with a banner reception for Mick in Manitoba. Henry’s father Albert, unsurprisingly, was a Second World War soldier who returned to Canada after the break up of his post-war marriage and lost touch. When he passed away in 1998, the search began for his son. Today, like many Americans, most of the British people we speak to tend to think of the classic stereotyped icon of a Plains “Indian” when asked about their image of Native Americans. Prior to the image-onslaught brought about by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, dime novels, and Westerns, this would not have been the case: and in the middle of the nineteenth-century, our media survey suggests, the Ojibwe were likely to have been their go-to reference point.

[1] Many esteemed veterans of the so-called Plains wars—the colonial invasion of the homelands of the Oceti Sakowin, Cheyenne and other nations—came to Britain with Buffalo Bill, and there is one more famous: Black Elk. Red Shirt, however, was undoubtedly the highest-profile Oglala member of the entourage, as he was made “Chief” of the Native contingent by Cody, who also probably overstated his past feats in order to generate publicity.

[2] In 1856, the papers also witness the visit of ten “Aborigines” from Walpole Island in southwestern Ontario, under the leadership of “Pe-to-e-Kie-Sie”, who had been lured to England under the pretense that they would be able to present “certain grievances” about the failure to uphold treaty terms before the Queen. It was believed at the time that they had in fact been brought over in order to be coerced into exhibition, a state that left them in destitution. The papers then track attempts to raise the funds to deliver them home. Walpole Island First Nation is unceded territory and home to Anishinaabeg (Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi).

[3] In 1843, Catlin was confronted by visitors to his “Indian Gallery” furious at his exhibition of the Ojibwe. Criticism of this and other displays was not at all uncommon in the press and among members of the establishment, as well as the general public. Baartman’s presence in London, meanwhile, just three years after passage of the Slave Trade Act, prohibiting the transAtlantic trade, was deeply scandalous, was protested, and generated a court case brought by the abolitionist African Association in November 1810, who sought to argue that she was being exhibited against her will. The case was ultimately dismissed, but remains controversial.

[4] Please note that Buffalo Bill’s claims for Red Shirt’s battlefield feats do not appear to match up with his actual biography.