Dr Kate Rennard (University of Kent)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

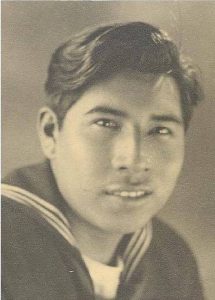

For Charles Norman Shay (Penobscot), a then 19-year-old medic serving with the 16th Infantry of the U.S. Army, the lead-up to the D-Day landings was, in many ways, isolating. Stationed at a base in England, the private first class and the rest of his company were “completely sealed off,” as were many other Allied troops. Cautious that their invasion plans might be leaked, Allied leaders ensured that the soldiers were “not allowed to take leave, permitted to intermingle with anybody.”

However, just before they shipped out from Britain, Shay had an unexpected visitor – Melvin Neptune, another Penobscot who he knew from his reservation. As Shay remembered: “when we talked, we didn’t talk about any impending military action that was going to be taking place. We just talked about our friends that we left behind or were already in the military service….wondering what our parents doing…It was very personal….I looked up to him [Neptune had seen a lot of combat action]…He gave me a lot of courage.” Even in the middle of Britain, with a major combat operation about to launch, Shay could rely on his Penobscot connections for support.

Around 44,000 American Indians and at least 3,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples saw active duty in the Second World War (the real number is undoubtedly much higher) and Shay was one of around 175 American Indian soldiers who landed on Omaha Beach on 6 June 1944 as part of the Normandy invasion.1 However, many other Indigenous North American servicemen and women also contributed to D-Day and experienced the preparations surrounding the operation while they were stationed in Britain. To commemorate the 75th anniversary of D-Day, this blog-post spotlights the stories of several of these veterans, giving voice to their experiences of the event through the lens of their time in Britain. The stories and experiences highlighted in this blog-post are diverse, from a member of a landing craft crew to a nurse to a combat engineer who was one of the first soldiers to land on Juno Beach, yet all gesture towards the incredible emotional and physical toll the invasion took on those involved.

Preparing for D-Day

Many of these Indigenous servicemen and women were stationed in England in the run-up to D-Day, doing basic training and preparing for the invasion. Shay recalled how they were “assigned living quarters in houses that people had vacated for the GIs” and that they “met very nice people in England and they were happy that we were there to participate in the invasion of Normandy.” George Horse (Thunderchild First Nation), however, had a more intense time, as he took part in combat training in Scotland, in the North Sea, as a combat engineer in an Elite Sapper Battalion: “The North Sea was very cold, but we were young and could take a lot of punishment. We had trained hard with an eight-mile run before breakfast every day, and soon become hard as nails. They told us it was preparation for D-Day. They never told us when or where it would happen, just somewhere in the English Channel, somewhere in France.”2

D-Day Operations

For Jeremiah Wolfe (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians), a Signalman Second Class in the U.S. Navy, the lead-up to D-Day had also been less than calm. Based near Falmouth, Cornwall, Wolfe recalled how the surrounding areas were regularly targets for German bombers: “just as soon as night came, as soon as it was getting dark, the guys begin to look around, and we heard motors a-coming, coming, coming, and it was bombers. And they were bombing around us. The bombs hit all around our base. They never did hit our base, but outside you’d see craters where the bombs hit, exploded.”

A few months later, he and the rest of his crew from the USS LCT 16 (Landing Craft, Tank), Amphibious Force, picked up their ship and began loading it with troops, equipment, and supplies, ready for the Normandy invasion. For Wolfe’s crew, however, the day did not go smoothly: “we got underway, headed for Normandy beach, Omaha Beach, Normandy. As we were sailing along, we got in sight…and there was already heavy firing going on, as we were moving right into that fire. When we landed, the commander of the rangers [the troops on board Wolfe’s ship] wouldn’t give the command for them to disembark…he just froze. And then our captain spoke up…” Eventually the commander got into one of the tanks and took it off the ship and onto the beach. It was almost immediately hit by German fire and exploded, killing the commander inside.

Treating Injured Soldiers

Those who were injured in the landing and fighting that followed but survived were often transferred to hospitals in France and England. Marcella LeBeau (Cheyenne River Sioux) worked as a nurse with the 76th General Hospital, which was located in Leominster, England in June 1944. After landing in Liverpool, LeBeau had been sent to Llandudno, Wales, for initial training and to await her assignment. In particular, she remembers experiencing the blackout and having to “direct our flashlight down, if we had one, so that the light couldn’t be seen” by any German aircraft.

Eventually, the 76th General Hospital was transferred to Leominster, a “barracks-type hospital,” where they were preparing for D-Day: “So we were set up there in Leominster, England, in our general hospital and waited for D-Day. And we were called to work one day, about 2:30 in the morning, to report to our duty stations. And we got our casualties then from the invasion…I think we had a few patients, you know for other reasons…We didn’t hear much on the news, you know, but we got our first patient about 2:30 in the morning and from then on we were busy all the time” with the high number of casualties. LeBeau would eventually be transferred to France and Belgium in August 1944 to serve in hospitals there.

These stories give us a brief insight into the D-Day contributions of Indigenous North Americans in Britain but there are many more. Three of those featured are from oral histories recorded as part of the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project, an incredible resource. So far, the Project has collected over 100 interviews with American Indian and Alaskan Native veterans who served in the Second World War, some in the European theatre and others in the Pacific, and is collaborating with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian to gather more.3 As the experiences of the four veterans that are featured here demonstrate, Indigenous North Americans contributed to the war experience in Britain in a variety of ways and yet they aren’t often recognised in histories of the conflict. By amplifying these veterans’ voices, this blog-post serves as a commemoration of their involvement in the Second World War, particularly here in Britain.

If you have any information about Indigenous North American visitors to Britain that you would like to share, please contact us via email, Twitter, or Facebook, or visit our website.

1 “Patriot Nations,” National Museum of the American Indian, accessed 5 June 2019, https://americanindian.si.edu/static/patriot-nations/world-wars.html#ww2; “Indigenous People in the Second World War,” Veterans Affairs Canada, accessed 5 June 2019, https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/historical-sheets/aborigin; Ramona Du Houx, “Medic at D-Day: The Humble Heroism of Charles Norman Shay,” American Indian Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Summer 2018), accessed 4 June 2019, https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/humble-heroism-charles-norman-shay

2 Quoted in Pamela Sexsmith, “George Horse – a veteran tells his tale,” Saskatchewan Sage, vol. 8, no. 2, 2003, accessed 5 June 2019, https://ammsa.com/publications/saskatchewan-sage/george-horse-veteran-tells-his-tale.

3 While you can search these oral histories by “race/ ethnicity,” it is not always clear how an interviewee has come to be designated “American Indian” and so researchers looking specifically for Indigenous veterans should be cautious. Some are clear about their tribal membership, while others who have this designation do not mention it at all in their interview, so it is hard to know what connections they have to any tribal nation. However, one interviewee specifically says that while he was born near the Chickasaw reservation in Oklahoma and his father always claimed that they had Chickasaw ancestry, he himself does not claim that identity. He is still recorded as being “American Indian” in the database.