Professor David Stirrup (Kent)

Principal Investigator, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

If you were in the crowds for the 2019 London New Year’s Day Parade, or happened to catch the TV coverage on 1 January, you may well have seen the Warriors of AniKituhwa from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI). Bedecked in their matchcoats and war paint they were pretty unmissable. As Jacqueline Fear-Segal explained in our previous blog-post, besides the invitation to the prestigious parade, they were in the UK retracing the footsteps of Cherokee ancestors in the 18th century. Far from the bustle—and the spectacle—of the parade, however, several of the BtS team met up with twelve members of the delegation (in mufti!) at the East End stores of the British Museum on 2 January, where the trip organizer, Dawn Arneach, had prearranged for them to view a selection of Cherokee objects held by the Museum. Given most of the group’s connections to the Cherokee National Museum in North Carolina, this opportunity was as important as the parade itself.

The reactions of the group to these objects was mixed. BtS Research Associate and resident museums expert Jack Davy might well explain that this is not uncommon. Unsurprisingly, being confronted by ancestral objects held in distant, colonial museums is usually a highly ambivalent experience. In this case, though, the apparent discombobulation in the room was at least partly generated by the relative newness of roughly half the objects, dating as they did back to collecting trips conducted by Jonathan King in the 1990s.

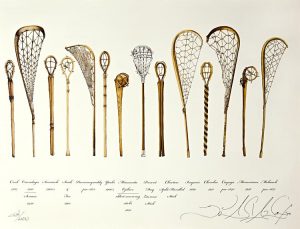

Most surprising of all to several of the group, perhaps, was a pair of ballsticks, carved by Jerry Wolfe. That these items generated mixed emotions was inevitable— their creator was a man they had spent time with, and who had passed away less than a year ago. On the other hand, while there was no doubt as to the quality of his craftsmanship, or the importance of including contemporary objects in the museum’s collections, they knew how these items were made, what they were made of: in short, these objects, unlike much older objects, could not tell them much they did not already know.

For me, however, they were a gateway not only to a different version of a sport I have been researching recently, but a lens into a vibrant and fast-growing act of cultural revitalization: Indian Ball.

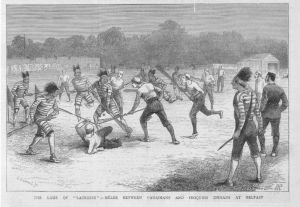

The sport I have been engrossed with is Lacrosse—as legend has it, so named in the 1600s by French Jesuit Father Jean de Brébeuf for the ballstick’s resemblance to a bishop’s crozier, la crosse d’eveque.[i] In 1876 a team from the Montreal Lacrosse Club toured Ireland and Great Britain, bringing with them a team of Mohawk Lacrosse players with whom they played a series of exhibition matches. They returned again in 1883, playing in cricket clubs and recreation grounds.

Although these tours were the first explicitly designed to publicise and export Canada’s new national sport, (the first formal rules were put down by tour organiser W.G. Beers in 1860), they were not the first occasion on which stickball had been played on these islands. Indeed, in the year of Canadian Dominion itself, 1867, eighteen Haudenosaunee Lacrosse players had toured the UK. Even before that, in August 1844, fourteen Báxoǰe, or Iowa, performers under the charge of American painter and impresario George Catlin and his fellow entrepreneur George H.C. Melody, had demonstrated their stickball game on the pitches of Lord’s cricket ground. Among various demonstrations of forest life, “The chiefs and ‘braves’ of the party will also engage,” an Era journalist wrote, “in a match at ‘ball-play,’ a game of the most exciting and amusing description, and requiring great skill.”

Most involved in the sport understand Lacrosse to have been invented by the Haudenosaunee—and it is true in essence. The modern version of the sport is played with sticks that evolved from the Haudenosaunee version of the ballstick, and it developed in interplay between Canadian and Haudenosaunee players. As the above anecdote shows, however, iterations of stickball were common among a variety of tribal nations. The Anishinaabe, for instance, also played what they called Baggataway (the Mohawk called it Begadwe)—variations of which were played by the Choctaw (kabucha) and of course the Cherokee (Dilasgalidi). The Umonhon, or Omaha, meanwhile, played a game called Tabegasi, involving propelling a ball along the ground with hooked sticks.

These historic accounts are, of course, interesting. The 1876 and 1883 tours certainly established the game in the UK, while those same teams probably influenced the headmistresses of Scottish girls’ schools to take up the game when they witnessed them play in Montreal in the early 1880s. Throughout the Lacrosse world, Indigenous origins of the sport are well known and recognised—the Iroquois Nationals are held in very high regard within the Federation of International Lacrosse. That profile, though, has rather overshadowed the involvement—and the alternative games—of other nations. An Ojibwe stickmaker, Frank Belleau, told me recently, for instance, that many younger Ojibwe are surprised to learn that Lacrosse was their sport, too. As with many parts of the US and Canada, stickball was banned in Ojibwe country by the colonial authories in the early 19th century, where it was seen as a threat for the way it brought community together and enabled the maintenance of traditions—though the excuse, of course, was that it was too violent. Frank is one of many involved in the game’s revitalisation, as was Jerry Wolfe.

The most important—and inspiring—aspect of this encounter with Jerry Wolfe’s handiwork, then, was not the sticks themselves so much as the conversation they generated with EBCI members Mike Crowe and Steven Michael Smith, both of them contemporary Indian Ball players. In the taxi ride from Orsman Road to the British Museum proper they showed me video footage of the games played at their annual festival and patiently answered my questions about the rules. Indian Ball is not Lacrosse. For all its similarities it is a very different game. While Lacrosse is a very physical game, Indian Ball is positively violent, adhering much more closely to the principles that led the Cherokee to call it “Little brother of war”—an activity for the training of young men in the rigours of battle. Like Lacrosse to the Haudenosaunee, it is also medicine—an important source of healing, of reckoning, and of offering to its originator, the Creator. As Lacrosse legend Oren Lyons explains of Lacrosse’s forebears, the game “is played to heal. Any individual can ask for a game. They might want to heal themselves. They might want to heal someone else. Then, ‘the whole community gets mobilized’”

Speaking as an ex-rugby player, it also looks like an awful lot of fun!

WATCH: ‘Cherokee Stickball for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’

WATCH: A full game of Cherokee Stickball

[i] French games using sticks and balls that already existed, such as la choule crosse, are the likelier analogue for the name.