Dr Kate Rennard (Kent)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

This blog-post launches First World War Native Stories (#WW1NativeStories), a series of short posts highlighting Indigenous North Americans’ experiences in Britain during the First World War, as we approach the Armistice centenary. These pieces are snapshots of some of the stories we have found so far and are not meant to be representative of Indigenous peoples’ experiences of this conflict. If you have any information (stories, images, artefacts, recollections, etc.) about Native North American visitors to Britain that you would like to share, please contact us.

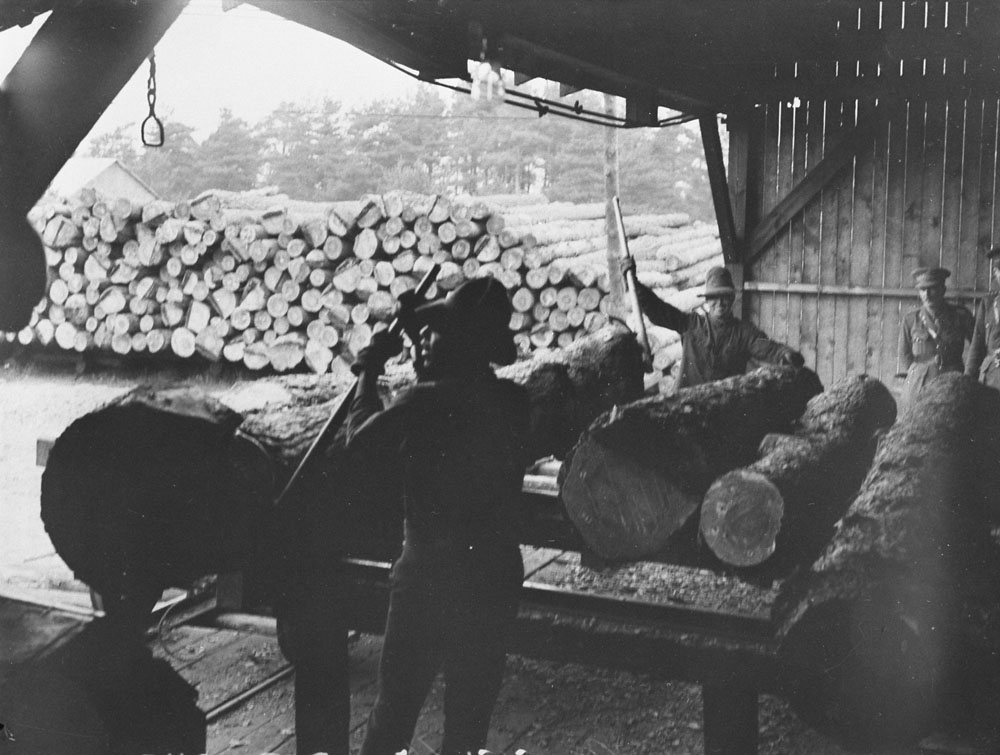

My favourite part of being an historian is uncovering the hidden stories, the ones that aren’t immediately obvious from a source but rather require a bit more digging and piecing together to understand the larger picture. I had to do this sort of historical detective work recently, when one particular newspaper story I found produced more questions than it answered. While searching through the British Newspaper Archive, I came across a short human interest piece in the Rochdale Observer from January 1918. According to the paper, a Lieutenant J. Jones, formerly of Littleborough, had recently brought a company of ten First Nations men with him to visit his hometown (all were part of the Canadian Forestry Corps). The article detailed their itinerary for this day, including touring a local mill, hiking to a nearby beauty spot, and visiting the cinema. However, it ended with the sad conclusion that while the company had initially included another First Nations man, he had been taken ill days before the trip and transferred to Rochdale Infirmary, where he had died. None of the Indigenous North American soldiers’ names were mentioned. Who were they? Why were they in Rochdale, instead of at the Canadian Forestry Corps’ base depot in Windsor?

These eleven men were a small fraction of the over 4,000 Canadian Indians who served in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in the First World War, although the exact number is hard to calculate since Indian Affairs lists rarely included Métis, Inuit and non-status Indians (those who belonged to a nation who had not signed a treaty with the government). As Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada notes, these soldiers “served in every major theatre of the war and participated in all of the major battles in which Canadian troops fought.” (For more information, see “Aboriginal Contributions during the First World War.”) I wasn’t entirely sure how to find these unnamed soldiers, especially given the tiny amount of information in the newspaper article. I started by searching through the Commonwealth and War Graves Commission website, specifically their “Find War Dead” database, where you can search by cemetery. “Rochdale” and “First World War” brought up 84 results and filtering it further to Canadian soldiers gave 2 names. Only one was listed as belonging to the Canadian Forestry Corps. The next step was to access the Canadian First World War personnel service records that Libraries and Archives Canada have made freely available on their website to double check the information given for that person. With the details from the newspaper report and his service record, this soldier’s story started to take shape.[1] See his journey mapped out here.

However, there were still so many unanswered questions. Who was this Lieutenant J. Jones and why did he take this group to Littleborough? Who were the other First Nations’ soldiers in this company? I returned to the Libraries and Archives Canada First World War personnel search and eventually found the Lt. J. Jones from Littleborough – Joseph Jones, whose listed occupation was Indian agent at Norway House in Manitoba. Further research revealed that Jones arrived in Canada in 1902 and by 1911 was serving as assistant principal of the Brandon Indian Residential School in southern Manitoba, before moving on to Norway House as the Indian agent in 1914.[2] He worked on building the new residential school that opened there in 1915, although it was notoriously overcrowded and many local First Nations communities refused to send their children there, especially after the children came home suffering from frostbite and malnutrition.[3] It’s little wonder then that Lieutenant Jones doesn’t seem to have been popular with local First Nations. In his recruitment efforts in 1917, he met with resistance from both band chiefs and the doctor of Norway House, particularly since “of the twelve Indians Jones had recruited, only three were accepted into the army. Furthermore, five had been rejected the previous year, a fact which Jones already knew.”[4] Despite these tensions with local First Nations, he clearly continued with his efforts. His personnel records show that he enlisted and then sailed on the HMS Metagama on November 27th, 1917, and landing in Liverpool on December 14th. At least four Native men who seemingly accompanied him to Rochdale travelled on the same voyage, including the soldier who would die there and his two brothers, although it was unclear at this point in my research whether he had personally recruited them.

The next step was to return to the British Newspaper Archive and search by name for the soldier who had died, as well as Lieutenant Jones and any more mentions of the Canadian Indians in Rochdale. One article provided further troubling insight into the Rochdale visit. Apparently, another soldier in the company had been arrested on the same day that his colleague had been admitted to Rochdale Infirmary, and was “charged with being drunk and incapable.” While this would not have been at all noteworthy if the soldier involved had been white, this case made the news, in part due to Jones’s speech at Rochdale borough police court. He noted that he was “in charge of eleven of the men whom he had recruited in Canada for forestry work at the front” and patronizingly explained that he “did not want to leave the men in London and as his home was in this district brought them to Rochdale, considering as well that they would be out of temptation.” He noted that Native peoples in Canada were not allowed access to alcohol, unlike in the UK, and that he was sorry the soldier had obtained it. Ultimately, the charges were dismissed. Jones was referring to the Indian Act, which was first passed in 1876 and sets out how the Canadian government interacts with First Nations. It is extremely controversial and has, since its inception, aimed to control the sale and consumption of alcohol in First Nations.

As Jones pointed out, there were notable differences between the rights of Indigenous servicemen and women when they were in Canada and the U.S. and during their time in Britain, an issue we’ll be exploring in more detail at the end of this series. Alcohol was just one such difference but it continued to have repercussions for Native veterans long after they returned to Canada. As the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples detailed, they had no access to Veterans’ Affairs (Indian Affairs took control instead) and they rarely had access to Royal Canadian Legion branches because Legions usually served alcohol. Those veterans subject to the Indian Act were prohibited from attending functions where liquor was served, meaning that they missed out on information on the benefits available to them and how to obtain them. This provision of the Act, which Jones had praised at the court hearing, actually “jeopardized [Native servicemen’s] receipt of veterans’ benefits,” leading to serious economic consequences for them.[5] For the soldier involved in this case in Rochdale, however, this did not personally affect him. His personnel records show that in July 1918 he was involved in an accident with a circular saw at the base depot’s mill in Windsor, which eventually led to the amputation of four fingers. He seemed to be recovering but by December 1918, he had returned to Canada, suffering from advanced tuberculosis. He passed away four months later.

While some questions about the visit are still unanswered, the larger story of how eleven First Nations soldiers ended up in Rochdale in December 1917 provides insight into the experiences of Native North American servicemen in Britain during the First World War. It also highlights some of the issues faced by First Nations people generally in this period, from the horrors of the residential schools Lieutenant Jones was involved in building and administering to the tensions between Native soldiers’ rights in Canada and in Britain. What initially seemed to be a mostly pleasant human-interest piece about soldiers visiting Littleborough therefore became a window into some of their bleaker experiences at home and in Britain in this period. While it is tempting to focus only on the more daring tales of Indigenous participation in the First World War, these darker stories provide a fuller picture of Native soldiers’ experiences of the conflict and of Britain.

[1] These stories are not well known and deal with sensitive topics. While there are various ways to approach this, I have decided not to name the First Nations’ soldiers who were involved in the Rochdale visit. I have not yet contacted families or the nations to which they belonged to consult with them and so I have decided to keep them anonymous in this blogpost.

[2] Susan Elaine Gray, I Will Fear No Evil: Ojibwa-Missionary Encounters Along the Berens River, 1875-1940 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2006), 165.

[3] The United Church of Canada Archives, “The Children Remembered: Residential School Archive Project,” https://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-locations/norway-house/ (accessed October 23, 2018).

[4] L. James Dempsey, Warriors of the King: Prairie Indians in World War 1 (Regina, SK: Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina, 1999), 30.

[5] Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Report of the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples (Ottawa, ON: Canada Communication Group, 1996) 550.

Hi Alan, thanks for your comment. We will be contacting the families and First Nations involved shortly. While it would be great to expand on these stories in the future, what we do with them depends on the wishes of the families and First Nations. Indigenous North American soldiers and their experiences in Britain are at the centre of one of our research strands though so we will definitely be sharing more stories over the course of the project.

I understand these are very sensitive topics, but do you intend to contact the families and expand on this in the future #WW1NativeStories series? I find any research/stories from either war both harrowing and also interesting. I’m sure there are so many more distressing stories that we don’t know and will most likely never know. A truly inspirational and brave generation.