Dr Jack Davy (UEA)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

One of the most complex aspects of untangling the history of Native Americans in Britain is that so often I cannot be sure whether the visitors about whom I am reading are really were who they said they were, or whom others said there were. For there is, both in Britain and North America, a long and ignoble history of what we today call cultural appropriation, the assumption and adoption and manipulation of ethnic identities to which one is not entitled for commercial, professional or personal purposes.

There have been recent protests in Britain from advocates of Native American sovereignty and authority, such as Project Board Member Dr. Stephanie Pratt, about the culturally insensitive, racist, use of the mascot ‘Big Chief’ by the Exeter Chiefs rugby team. ‘Big Chief’ is a gross caricature of a Sioux chieftain, an ostensibly false and conspicuously vulgar standard bearer for the many other imitators who came before, assuming false identities and deliberately, though not always mendaciously, misrepresenting the indigenous people they aped.

This type of crude appropriation began early; when three chieftains of the Cherokee came to London in 1762 to negotiate a treaty with King George III, led by Ostenaco, they were pursued about town by “three Men, [who] in imitation of the Cherokee Kings, and having their Faces painted like them, have been shewn at many of the public Places for the real Indians.” (Bath Chronicle, 12/8/1762) Much of the riotous behaviour attributed to the Cherokee presence in the press may well have been perpetuated in reality by these impostors and the crowds they drew.

The example which I discuss today is a tragic story of family, of terrible loss, and the extent to which what I am coming to call ‘Indian kayfabe’, the rigorous attachment to a fraudulent narrative for commercial purposes, was stretched in the early twentieth century. In their steady maintenance of a fictional reality, Wild West shows and other spectaculars practiced subversions of reality similar to those found in modern professional wrestling, in which the scripted events of wrestling bouts are maintained as reality even when everyone, from performers to promoters to audiences, knows them to be false. This practice is known as ‘kayfabe’, a word of obscure, possibly Yiddish origin, and was taken to extremes in this example by a non-Native promoter desperate not to lose his audience.

In 1909 it was noted that audiences were turning away from Wild West spectacles; they were becoming boring. One reviewer asked “Do the boys of England still relish their Fenimore Cooper, or has the taste for scalping forsaken them?” and went on to lament that a Wild West show would once “have gladdened the heart of the boy of a score years ago or so, but has not the taste for it been glutted?” (Morning Post, 7/12/1909)

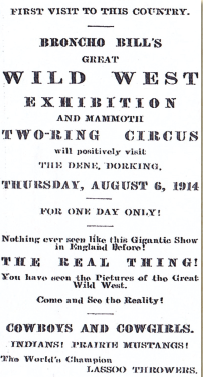

Such was the environment in which Broncho Bill’s Wild West Show, a cut-rate imitation of Buffalo Bill’s spectacular, appeared in 1914, featuring only a handful of Native Americans as an attachment to a larger touring circus. The centrepiece of the show was a family of Sioux performers known as the Denneys. Their history, as relayed by Broncho Bill, was that the family had travelled to Britain from their home on the Pine Ridge Reservation in the Dakotas in search of work, and had taken up with the travelling show on its tour of the West Country.

On the evening of 19th April 1914, at Barnstaple, the Denney family were sleeping in a tent, on a blanket laid on straw, when they awoke to find the tent on fire – a candle lit to comfort their six-year old son Henry had fallen over in the night. Robert pushed his wife Louisa through one end of the tent and snatched up Henry and ran through the other as his elder children, Frederick and Florence escaped with baby Clara under the tent wall. Turning to the burning tent, and afraid it would ignite other tents nearby, Robert hauled the structure down. The tent collapsed in on itself and on top of Louisa who, unaware that her husband had brought out Henry, had returned to find her son. Henry, momentarily unattended and seeing his mother enter the tent, leapt from the grass and followed her inside. Mother and son both died a few hours later from extensive burns.

The following day the coffins were conveyed through Barnstaple on an open carriage adorned with flowers; Henry’s small white coffin had, morbidly, been inscribed with the motto “the flower fadeth”. The procession departed from the Infirmary, winding though the town to Holy Trinity Church, the route lined with local citizens, who had subscribed to meet the cost of the funeral; Broncho Bill had forwarded the money, but made it clear that Robert was to repay it from his wages. The Mayor of Barnstaple had stepped in with a large donation and encouraged his fellow citizens to follow suit.

Behind the coffin solemnly walked the family, Robert bandaged with his “jet black hair hanging in plaits”, his son Frederick similarly swathed in bandages and his daughter Florence wearing a simple black wool dress and hat. Behind them came Broncho Bill in full cowboy costume, the newspapers recording the “sympathy of both the white and coloured travelling companions of the deceased.” Louisa and Henry were laid to rest together in an unmarked grave in the churchyard, where they remain. (Exeter & Plymouth Gazette, 22/4/1914 & 24/4/1914; North Devon Journal, 23/4/1914).

Throughout the tragedy, its aftermath and the funeral, all public speeches and engagements were led by Broncho Bill, who ensured that the full story of the family from Pine Ridge went into newspapers across the country, reported in places as diverse as the Londonderry Sentinel, the Dundee Courier and the Hull Daily Mail (all 21/4/1914). Nowhere was any part of this story questioned.

And yet in its fundamentals it was false. The Denneys were not from Pine Ridge, they were not Sioux, they were not even Native American. Research has uncovered that Robert Denney was born in Tobago around 1868, and had spent most of his life working as a coal porter on the London docks. Louisa, whose children were the four survivors of nine babies, had been born in Poplar in around 1875. Broncho Bill himself was not, as he claimed, a former sheriff from Arizona, but it seems is most likely to have been an entrepreneur from Wolverhampton named Johnny Swallow.

Quite how this presumably mixed-race family from the London docks became engaged as Sioux performers by Broncho Bill may never be known, but what strikes me most strongly is the remarkable strength of the lies which surrounded them. Even in the depths of disaster neither the family nor their employer gave any public hint of their true origins; they maintained a stoic silence that furthered the fiction that they were of Native heritage.

Other Native performers of unimpeachable heritage famously struggled with this issue of blurred realities; if the ‘kayfabe’ slipped, their audiences could turn on them: Hutgohsodoneh, known to the press as Deerfoot the Seneca Runner, really was a Seneca man, who grew up on the Cattaraugus Reservation in New York. In 1861 he participated in fixed races against staged opponents across England, and when this was exposed there was fury in some quarters: “the Deerfoot business was nothing but a tremendous ‘sell’, that the paint and feathers were nothing but a masquerading costume to attract the multitudes who paid to gape” wrote one commentator (Belfast News-Letter, 12/12/1861)

Others took precautions: twenty years after the Hutgohsodoneh scandal, Waubuno of the Delaware toured Britain in 1883, speaking at temperance rallies and occasionally performing with a music hall troupe. Wherever he travelled, he carried a letter of recommendation signed by Dr. Oronhyatekha of the Six Nations Reserve, near Brantford, Ontario, who was President of the [Native] Grand Council of Ontario and an alum of the University of Oxford, one of the best-known Native gentlemen in England. This letter acted for Waubuno as a ward against inevitable accusations of fraudulent identity (Shields Daily News, 31/5/1883).

I know nothing of the fate of the survivors of the Denney family. They drop out of press accounts of the show and I have had no luck in locating them by any other archive. Presumably Robert Denney, freed from his employment, was once again at liberty to resume his real identity and heritage and, hopefully, rebuild his life and family as best he could. But the way in which, at the worst moment of his life, he was forced to continue to pretend to be what he was not, shows just how strongly the ‘kayfabe’, the pretence of indigeneity and the insistence of authenticity in profoundly inauthentic contexts, runs right through the history of Native American engagements in Britain.