Dr Jenny Hale Pulsipher (Brigham Young University)

Beginning in the sixteenth century, hundreds of Native people from the Americas crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Britain, a stream of immigration recounted in such recent works as Coll Thrush’s Indigenous London, Jace Weaver’s The Red Atlantic, and Alden Vaughan’s Transatlantic Encounters. Many were carried against their will as enslaved captives; others agreed to go as diplomats in the company of colonial agents, who hoped the splendours of the English court would induce them to fall into line with their own vision of Natives as allies to the dominant power of the English Empire. Some, trusting in the promises of English monarchs to defend the rights of their Native subjects, went or sent their appeals with English colonists whose interests aligned with theirs. Few American Indians ventured the Atlantic passage on their own, for their own reasons. One who did was John Wompas, a seventeenth-century Nipmuc Indian from the central highlands of Massachusetts.

The name John Wompas carries none of the recognition value of, say, Pocahontas, Powhatan, or King Philip (Metacom). Wompas was not a leader, not someone English colonists naturally turned to as a source of alliance or land. Instead, he was a “common Indian,” or, as his relatives pointed out, “no sachem.” John, partly raised among the English and educated in English schools, including a stint at Harvard College, was well acquainted with the languages and cultural and political norms of both Native and English societies, and he used that knowledge to his own benefit. Rejecting his English mentors’ plan that he enter the ministry, John instead became a transatlantic sailor and sold Native land to fund his adventures. When his aggrieved kin pushed colonial authorities to block these sales, John took ship to London, secured an audience with the king, and received a letter commanding justice for “my subject John Wompas.”

While little evidence of John’s time in London remains, hints in his two petitions to the crown, court cases, land deeds, and a will help us sketch the outlines: He lived in Stepney and Radcliffe, in the maritime neighbourhoods of East London. He spent nearly a year in a debtors prison “in or near” London. He appeared personally before Charles II and secured the aid of the king and his Privy Council in 1676. He hoped to resume his land sales on his return to Massachusetts in 1677 but was again blocked by colonial authorities. In response, he became an outspoken critic of the English colonial leaders, deriding them publically for their abuse of him and of all Native people. In 1678 he returned to England to petition the crown. On this second visit, John died, but not before selling thousands of acres more of Native land to English acquaintances and then, in a striking reversal of his self-serving ways, bequeathing his Nipmuc homeland of Hassanamesit to his Native kin in his will.

John’s dramatic experiences on both sides of the Atlantic and in both English and Native worlds upend common wisdom about the defeated and subjected Natives of New England at the end of the seventeenth century. Upsetting expectations is emblematic of John Wompas’s entire life. He was a Harvard-educated scholar who became a sailor; he called the Nipmuc village of Hassanamesit his home but spent his adult life dwelling among the English of Roxbury, Boston, and London; he claimed the right, by inheritance, to lead the Nipmucs, but elders of his tribe insisted he was “no sachem”; he cheated his kin of their lands by selling thousands of acres of Nipmuc Country to the English, then bequeathed all of Hassanamesit to his Nipmuc kin in his will; he secured an audience and letters of support from the king of England, who called him his “loyal subject,” and he was derided as a drunk and vagrant by Massachusetts officials, who threatened to sell him into foreign slavery.

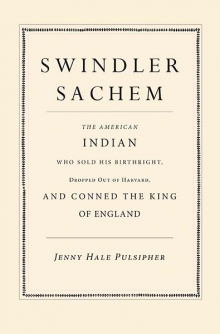

The contradictions in John Wompas’s life reflect a gap between expectations and reality, not just among readers of history, but among those who lived it. Colonial leaders and the English Crown made promises to John Wompas and other Natives about equal status, education, and royal protection that fell far short of what Indians actually received under the political and social reality in place by the last quarter of the seventeenth century. But even under the pressures of an expanding English empire and dwindling Native populace, John and a number of his kin adapted and survived, often by using English legal systems and norms to their own advantage. John’s final act was writing a will, recorded at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, that bequeathed his homeland to his Nipmuc kin. That legal document, which required his English heirs to recognize Native title to Hassanamesit in order to claim the lands he bequeathed them elsewhere, become an instrument for preserving Nipmuc land, as John no doubt intended. Some of that land remains in Nipmuc hands to the present day–the only Native land in Massachusetts to remain continuously in the possession of its Native owners. John Wompas’s extraordinary story, recounted in my new book, Swindler Sachem: The American Indian Who Sold His Birthright, Dropped Out of Harvard, and Conned the King of England (Yale University Press, 2018, available here), gives us a new perspective on Native interactions with the early English empire, showing how an ingenious Native man could turn the tools of colonialism to the benefit of the colonised.