This is the text for a catalogue essay accompanying the forthcoming online exhibition ‘Fascinating Fears’ curated by Kent students taking the undergraduate Art History module Print Collecting and Curating.

Two men take refuge from an outbreak of cholera in New York in a remote cottage on the banks of the Hudson River. One is anxiously following the daily news of deaths from the city with ‘abnormal gloom’, his mind grasping at omens; the other, a rational type, is aware of the ‘substances of terror’ but ‘of its shadows’ he has ‘no apprehension’. One day, pausing in his reading to look out of the window at a distant hill whose covering of trees had recently been removed by a landslide, the melancholic suddenly sees something that makes him doubt his sanity: a monster.

Hurtling down from the summit is a creature the size of a ship, tusks protruding from a head covered in shaggy hair, with two sets of wings spread over with enormous metal scales, and on its torso the representation of a hideous skull. Just as ‘a sentiment of forthcoming evil’ irresistibly seizes the man, the monster’s jaws, situated at the end of a long proboscis like an elephant’s trunk, emit ‘a sound so loud and so expressive of woe’ that he collapses in fright.

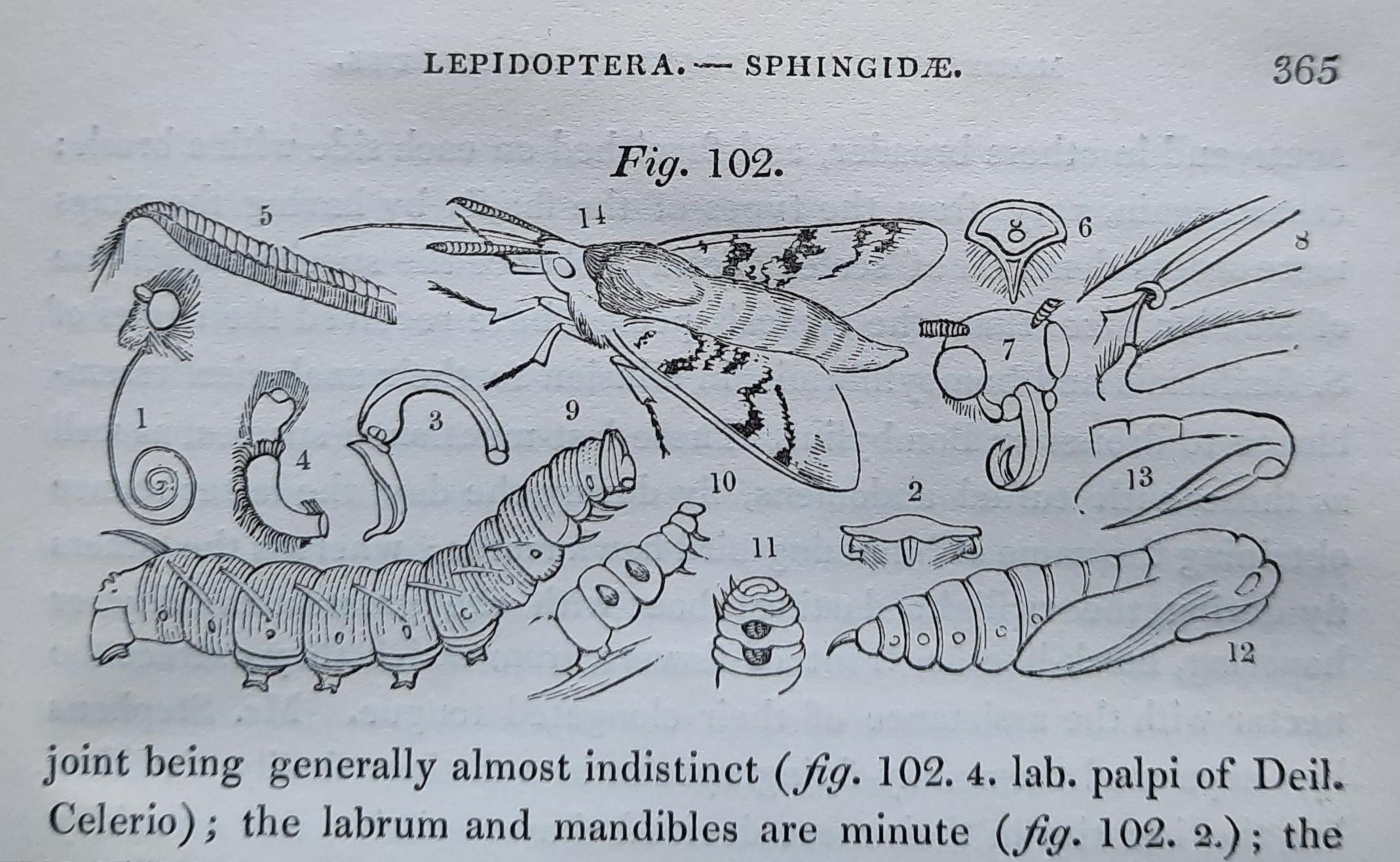

This is the scenario of the startlingly contemporary tale of horror, The Sphinx, written by the American author Edgar Allan Poe in 1850. While the narrator fears that the sudden vision of a monster is the ‘omen of my death’ or the ‘forerunner of an attack of mania’, his more scientific friend is able to deduce from the detailed description given to him of the fiend, and with the aid of a nearby handbook on Natural History, that the creature is nothing more than a Death’s-Head Hawkmoth ‘of the genus Sphinx, of the family Crepuscularia, of the order Lepidoptera’, which far from thundering down the far-away hillside, was simply crawling across the surface of the intervening window. Whether something is monstrous and threatening, or commonplace and harmless, is simply a matter of perspective it seems. Or rather of perception (Noël Carroll refers to ‘the magnification of entities’ as one key ‘recurring symbolic structure for generating horrific monsters’).[1]

The Death’s Head Hawkmoth (Acherontia Atropos of the Sphingidae) is, like other moths of its type, known as a sphinx because the caterpillars ‘are remarkable for the attitude which they ordinarily assume, whence they have obtained the generic name of Sphinx, from their supposed resemblance to the figures of that fabulous creature’. The noted Victorian entomologist, John Obadiah Westwood, went on to describe how ‘the Death’s-head moth is the largest European Lepidopterous insect, and derives its name from the singular skull-like patch on the back of the thorax. This marking, together with the shrill sound which the insect emits when alarmed, has rendered it an object of alarm to the ignorant in seasons when it has abounded’.[2] Reports in the popular press described the Death’s-Head Hawkmoth as ‘a messenger of pestilence and woe’ and a ‘harbinger of impending calamity, such as war, pestilence or famine to the community or sudden death to the particular individual unfortunate enough to catch sight of the moth’.[3] It is in this role as a symbol of doom that William Holman Hunt introduced the Death’s-Head Hawkmoth into his superficially idyllic pastoral scene The Hireling Shepherd of 1851 (Manchester Art Gallery). Yet for Charles Darwin, the sphinx moth was an example of the fundamental normality of a hybridity that might appear monstrous, but which actually results from an underlying homology of forms. In On the Origin of Species (1859) he asked: ‘What can be more different than the immensely long spiral proboscis of a sphinx-moth, the curious folded one of a bee or bug, and the great jaws of a beetle? – yet all these organs, serving for such different purposes, are formed by infinitely numerous modifications of an upper lip, mandibles, and two pairs of maxillae’.[4]

The mythical Sphinx from which the sphinx moth derives its name is itself a monster: part lion, part man (and occasionally woman) in Ancient Egypt, and a combination of the body of a lion, the wings of a bird, and the head of a woman in Greek mythology. In Egypt, the sphinx was the imperturbable guardian of temple and tomb, protecting secrets that only the initiated should enquire into. The Renaissance philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola saw the sphinx as the symbol of the ‘enigmatic veils and poetic dissimulation’ that should preserve the sacred mysteries of nature from the ignorant.[5] The Greek sphinx is best known for its tantalising riddle posed to travellers to Thebes, and for the cruel punishment inflicted on those who failed to answer it correctly: ‘What is that which has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed’ (itself a description of a monster undergoing a process of metamorphosis like the sphinx moth that morphs from larva to pupa to imago).[6] The hero Oedipus defeated the Sphinx by solving the riddle: ‘Man’. For this feat he was made King of Thebes, but ‘predestined to some awful doom’ he brought a terrible plague down on his city through his unknowing murder of his father Laius and his incest with his mother and queen Jocasta (‘horrors so foul to name them were unmeet’). Responding to his citizens’ pleas and the Delphic oracle, Oedipus once again ‘makes dark things clear’ only to find that he is the cause of the sickness and the ‘fell pollution that infests the land’.[7] As is well known, Sigmund Freud named the ‘Oedipus Complex’ after the tragic king of Greek legend, whose fate describes one of the central concepts of Psychoanalysis which aims to shed light on the primordial drives and fears that shape human consciousness. This is the nebulous terrain explored by Julia Kristeva in her Powers of Horror, where she describes the force of ‘the abject’ that ‘simultaneously beseeches and pulverizes the subject’.[8]

London is a city haunted by sphinxes, mainly of the Egyptian variety. Two large bronze sphinxes modelled by Charles Henry Mabey, cousins of the great Sphinx at Giza, guard the obelisk of Thutmose III (c. 1450 BC) on Victoria Embankment (commonly known as Cleopatra’s needle), while smaller female variants form the armrests of nearby benches. Similar but stone versions can be found in Crystal Palace park, and London’s graveyards also feature frequent sphinxes.

Domestically-sized Egyptian sphinxes, accompanied by obelisks, watch over the thresholds of the Victorian villas of Islington’s Richmond Avenue, while more Greek and feminine sphinxes can be found reclining on the doorsteps of Primrose Hill.

A brooding bronze example of the Greek sphinx, stretching her wings and flanked by voluptuous reclining nudes, is part of a magnificent bronze over-door at 24 Lombard Street in the heart of the City, while the gates into Green Park on Piccadilly are protected by two rather delicate and rococo lead sphinxes (perhaps by the eighteenth-century sculptor Henry Cheere).[9]

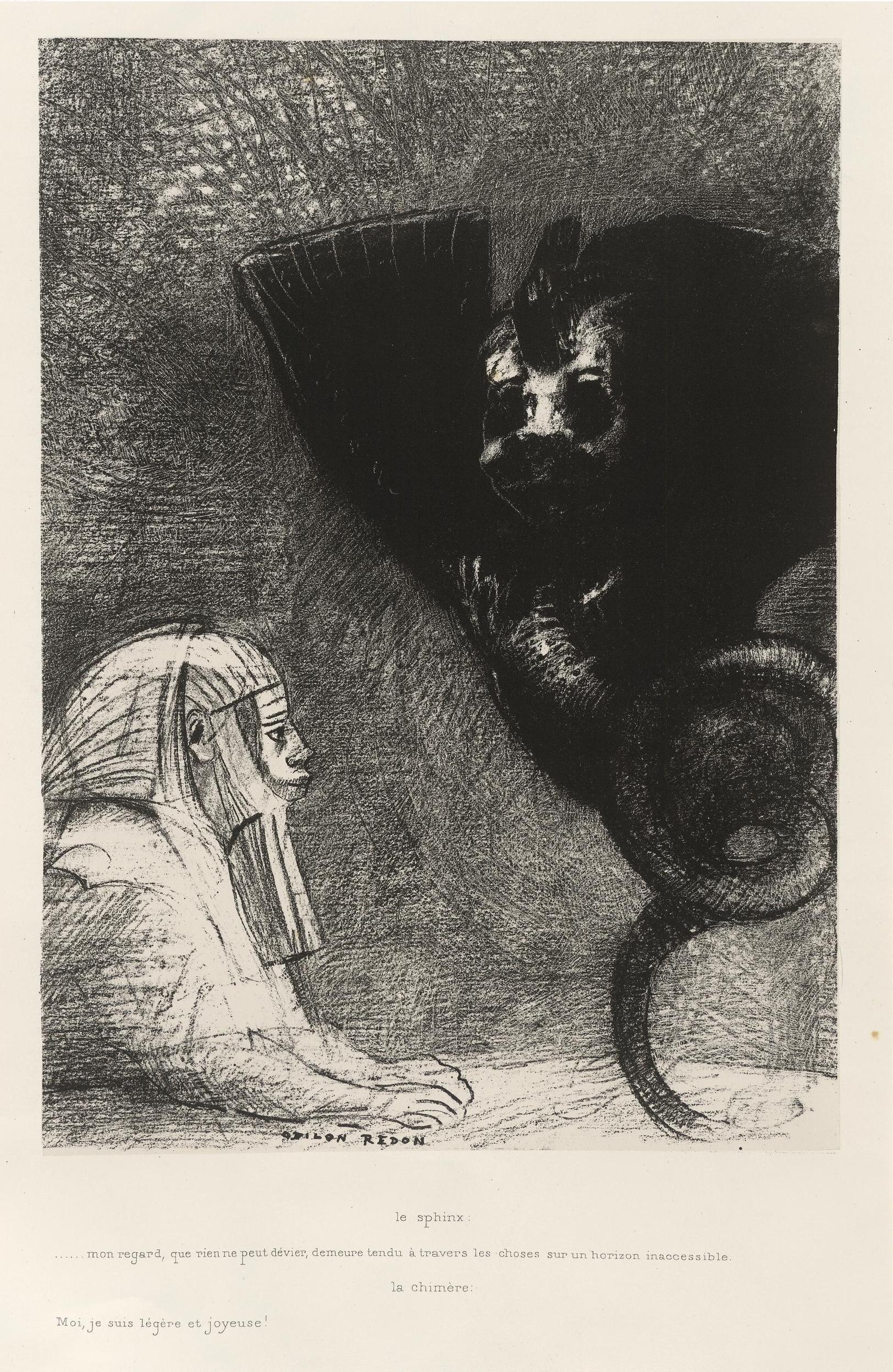

Finally, the calm features of the pharaoh Khafre stare out over Kensington Gardens from the mass of marble representing Africa at the corner of the Albert Memorial (by William Theed); the sphinx here is reclining beside a camel bearing an Egyptian queen. Stony and impassive, this sphinx is perhaps staring down the chimera that struggled with it in the desert in Gustave Flaubert’s Temptation of St. Anthony (1874). The symbolic psychomachia of chimera and sphinx – illustrated by Odilon Redon in his 1889 lithographs accompanying Flaubert’s text – represents the rapid and instinctual power of association that alerts the mind to danger, those imaginative fantasies giving rise to the fascination of fear, and the solid ground of reason that through interrogating these intuitions restores calm. Wintry blasts of a freezing northerly wind play around the Albert Memorial, even as the cherry blossom and daffodils herald Spring, but the sphinx remains indifferent to them, seeming to say ‘I keep my secret – I dream and calculate’.[10]

What do these hieroglyphs of memory thrown up by the city represent? They cannot be merely decorative? How conscious are we, even now, of the abject fascination and the sacred fear of the monster? Of a creature so alien and other that its mere existence disrupts the paradigm in which we can make reasonable assumptions about what it is to be human. Are London’s sphinxes a confident presence reassuring us of the power of science, or symptoms of a repressed and guilty secret that man is indeed the monster – the zoonotic pathogen continually infesting itself through the unknowing breach of taboos whose obscure origin lies in the instinct for self-preservation. ‘I find it useless and tedious to represent what is, because nothing that is satisfies me,’ wrote Charles Baudelaire. ‘Nature is ugly, and I prefer the monsters of my fantasy to the triviality of positive reality’.[11] With all due respect to a great poet, it is time to get real. Nature is beautiful, terrifying and monstrously angry. One of the more unsettling Egyptian relics in London, to those who notice it, is the stone bust of the lion-headed Sekhmet (c. 1320 BC) placed above the entrance to Sotheby’s auction house in Bond Street. Like the Sphinx a monstrous combination of lion and human, she is a blood-thirsty goddess, the ‘Lady of Pestilence’, an avenger punishing sins, who had to be tricked into drunkenness by the gods to avoid the extinction of the human race. Yet, the power of Sekhmet can also bring healing as well as destruction, as she is the ‘One who loves Ma’at’ – the principle of justice, or natural balance, that may yet save us.

Ben Thomas, 14/4/21

[1] Noel Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror or Paradoxes of the Heart, New York and London: Routledge, 1990, p. 49.

[2] J. O. Westwood, An Introduction to the Modern Classification of Insects, London, 1840, II, pp. 366-67.

[3] ‘The Death’s-Head Moth’, Chatterbox, 15, 9 March 1868; Harold Bastin, ‘The Death’s-Head Moth’, The Illustrated London News, 215, 5766, 22 October 1949.

[4] Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, chapter 13: Mutual Affinities of Organic Beings: Morphology.

[5] Cited in Edgar Wind, Pagan Mysteries in the Renaissance, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980, p. 17.

[6] Different versions of the riddle survive from antiquity: this is the version in Apollodorus, The Library.

[8] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, p. 5.

[9] Or is the Lombard Street monster a chimera? The 1914 sculptural group by Francis William Doyle Jones is entitled Chimera with Personifications of Fire and Sea in Philip Ward-Jackson’s Public Sculpture of the City of London, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003. The chimera is usually a hybrid of lion, goat and snake as in the bronze Chimera of Arezzo (400 BC) in the archaeological museum in Florence. Doyle Jones’s combination of a woman’s head with the body of a lion and bird’s wings seems more like a sphinx.

[10] Gustave Flaubert, The Temptation of St. Anthony, chapter VII.

[11] Charles Baudelaire, ‘Salon de 1859’, Baudelaire: Oeuvres Complètes, ed. Claude Pichois, Paris: Gallimard, 1975-76, vol. 2, p. 360.