‘Do you like Frida Kahlo?’ This was a somewhat unexpected question to receive at the coffee-break during an American Summer School on British art, in the wood-panelled common room of an Oxford college, and coming from an elderly student who had remained silent throughout that morning’s seminar on Pre-Raphaelite painting. It was also a little unexpected because back in the mid-1990s fewer people knew about Kahlo than do now, at least in Britain. ‘Like her?’ I blurted out, ‘I love her!’

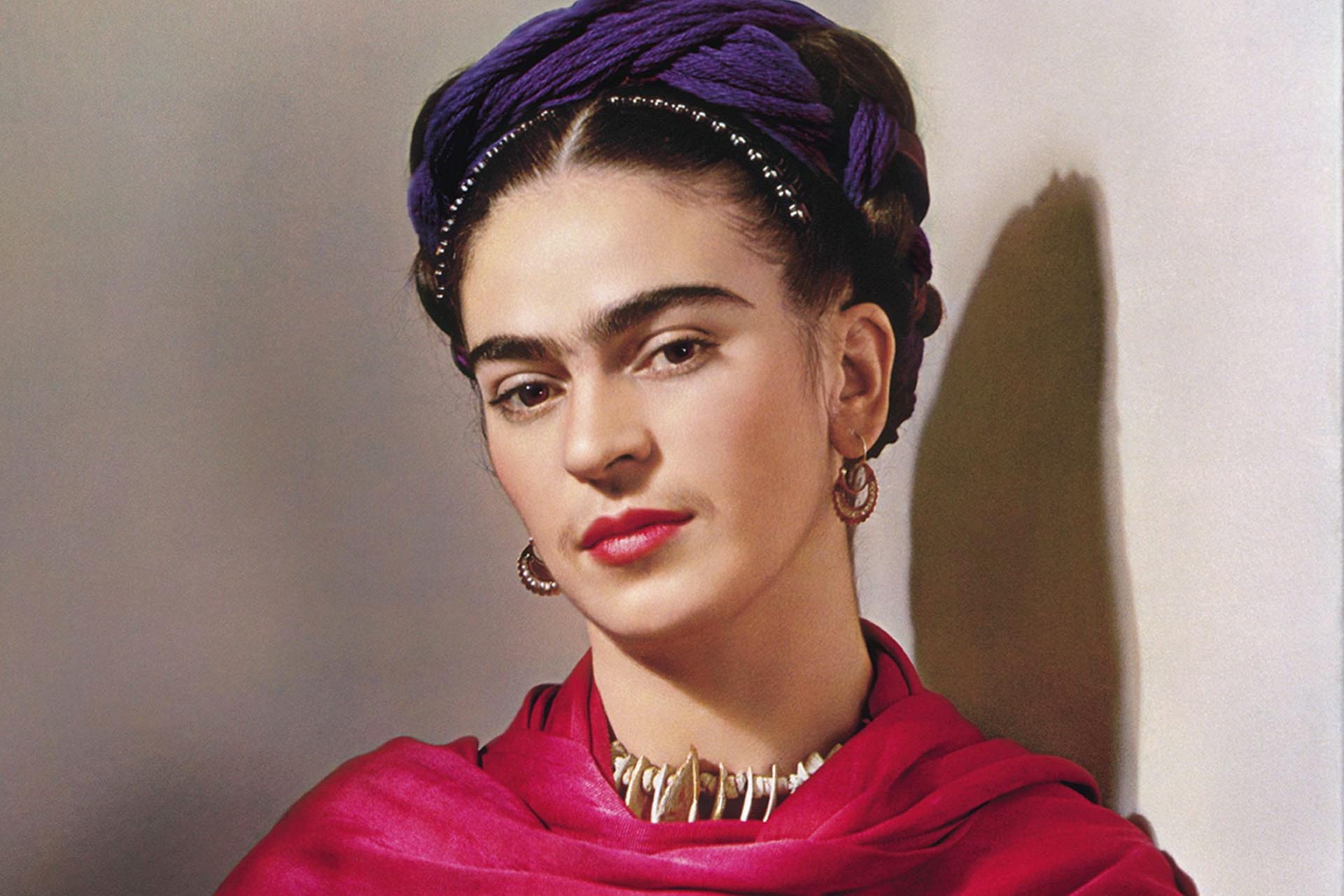

The face of my interlocutor broke into a broad smile. ‘Oh good! I thought perhaps you would’, she said. I rambled on about my enthusiasm for Kahlo’s art, and how I had recently visited her home, the wonderful Casa Azul in the Coyoacán district of Mexico City. After listening politely, the dignified woman I was speaking to revealed that she had known Frida. Although she was now an American, she had grown up in Mexico City, where her husband had been Diego Rivera’s eye doctor. Mexico’s leading muralist, and Frida Kahlo’s husband, had been so grateful for the treatment he had received that invitations to fashionable parties had followed. At these, Frida had stood out through her forceful presence and because of the sheer eccentricity in a bourgeois milieu of dressing in the colourful clothes of a peasant. Listening intently, I sensed the long-standing respect of one woman for the unapologetic bravery of another, for her refusal to be anything but herself.

In the presence of this lived memory, my own perception of a glamorous personality gleaned from library books and tourist trips seemed rather superficial (I have not been tempted subsequently to claim ‘Frida’ as an imaginary friend, no matter how seductive that daydream may be, and she has remained ‘Kahlo’ for me, a more distant but serious figure). It was one of those moments where an encounter with the past conveys tangibly that history involves the communication of feeling, and not just the analysis of facts. And that, of course, is what Kahlo’s art does so well, whether that feeling is the bitter anger at misogynist savagery of A Few Small Nips (1935), the stoical suffering of The Broken Column (1944), or the heart-broken, hybrid candour of The Two Fridas (1939).

The truthful and unconventional quality of Kahlo’s art appealed to the Surrealists, who claimed her as one of their own. In 1938 when he visited Mexico, André Breton was impressed by Kahlo’s Self-Portrait Between the Curtains (1937) which she had painted for her lover, the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Sensing the subversive quality of this ironic performance of romanticised femininity, Breton described it as ‘a ribbon around a bomb’. For her part, Kahlo was more taken with Breton’s wife, Jacqueline Lamba, with whom she spent a great deal of time while the star-struck Breton followed Trotsky around (for which see Whitney Chadwick’s The Militant Muse, 2017). On the whole Kahlo thought that the Surrealists were ‘coocoo lunatic suns of bitches’ (as she put it in a letter to her American lover, the photographer Nikolas Murray; her English was always a little erratic…). While Breton may have seen her art as the unconscious and autonomous expression of ‘pure surreality’, proof of what Simone de Beauvoir would dismiss as the myth of the ‘eternal feminine’, for Kahlo, her work was simply and always ‘the frankest expression of myself’ and also a contribution to ‘the struggle of the people for peace and liberty’. Although far from being a perfect husband, Diego Rivera at least understood Kahlo well enough to paint her handing out guns at the revolution (in the 1928 mural Distributing Armsin the Ministry for Public Education in Mexico City). Rather than a ‘ribbon around a bomb’ perhaps a better emblem for Kahlo’s art would be the plaster corset, worn to support her spine damaged in a street-car accident in 1925, decorated over the heart with the hammer and sickle?

This post by Ben Thomas is reposted from the School of Arts blog celebrating International Women’s Day.