Dr Jack Davy (University of East Anglia)

Research Associate, ‘Beyond the Spectacle’

In this blog post I am going to introduce my personal research programme within the ‘Beyond the Spectacle’ project, one of the several concurrent strands which will contribute towards the project’s ambitions laid out by David in the inaugural post.

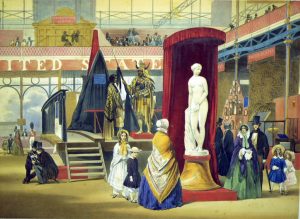

I’m going to do so with reference to an image I located in the collections of the Nottingham Castle Museum; it is a lithograph print of 1851 showing a view of one of the displays of the Great Exhibition of that year.

The Great Exhibition was the biggest and most spectacular extravaganza of the Victorian era. Organised by a committee led by Prince Albert, it featured 13,000 exhibits from 44 countries within a custom-built glass display hall dubbed the Crystal Palace. More than six million people from all over the world attended the exhibition, which was designed to, and to an extent achieved, an ambition of centring Britain as the hub of world industry, technology and economic power.

One of its less explicit ambitions was to justify the British Empire, then growing inexorably. The Empire was not universally popular in Britain at the time; it was expensive and entailed almost constant conflict to sustain. The exhibition featured large displays from the Empire as a method of connecting the disparate peoples and places to one British Imperial identity.

‘Beyond the Spectacle’ looks at Native American presences in the British archive, and this lithograph is a good example, although the Native people in this image are in fact wooden dummies, originally created for George Catlin’s 1845 touring Native American show which also featured living exhibits of Iowa people, who danced for the Royal family at Windsor Castle. This is part of the United States’ display at the exhibition, and it features a tipi and two figures. The spear-wielding man, on the right, is wearing the ceremonial regalia of a Plains tribe, probably the Blackfoot of modern Montana and Alberta. His female companion however is from another people entirely; she is wearing a Chilkat robe, a mountain-goat wool ceremonial blanket of startling complexity found among the Tlingit peoples of the ill-defined borderlands between Alaska (then Russian) and what would become British Columbia, nearly a thousand miles from the Blackfoot homelands.

The display is a confection, a fake. It is a mock-up of disparate peoples presented together in a striking way as part of a colonial effort to rationalise the then-ongoing seizure of Native lands and resources in both the Plains and the Northwestern forests. The clothing and objects displayed at the exhibition however were genuine, taken by fair means or foul, from Native communities in the places depicted. It is a theme often found in indigenous studies; the fig-leaf of authentic objects placed in a conspicuously inauthentic environment. To adapt a term, these conflicting narratives might be characterised as examples of “ethnodrama”, a hybridised confection of an “authentic” scene created for an unfamiliar audience.

My project connects with this issue because I am examining the intersection of objects, Native peoples and the British public within environments specifically designed for this type of ethnodrama: the museum.

Most British people are familiar with the concept of museums. Millions of school children visit museums in this country every year. Many museums, particularly those in larger cities, have galleries of “world art”, examples of objects from countries all over the globe, arranged together in attractive displays of exotic curiosities. What is rarely made explicit is the context in which these collections were assembled and the very reasoning behind the institutions in which they sit.

Many people will have heard of the high profile cases of objects which may have arrived in Britain through illegal or unethical means, such as the Parthenon Friezes in the British Museum or the Cambridge Benin cockerel. What is less well understood is that many other objects, although ostensibly legally removed from their places of origin, were collected in circumstances of profound inequality. They were “gifted” in circumstances where the giver was unable to refuse, or bought from people who were starving due to poor food management by colonial authorities. The objects travelled around the world and found their way into British public institutions, where they remain for our viewing pleasure.

In recent years however, some of these colonised people are seeking out objects made by their ancestors and coming to Britain to find them. People come from the Pacific, Africa, Australia, Asia and South America, but many the pioneers of these modern voyages of discovery are Native North Americans. Real people with real ambitions, not dummies positioned on a stage.

Some of these visitors come seeking repatriation, the return of the objects themselves, but most are in search of something else; knowledge. In both the United States and Canada, aggressive programmes of repression of indigenous ceremonial, spiritual, linguistic and material culture caused untold damage to indigenous ways of life in the last two centuries. For some peoples these objects surviving in UK museums are literally the only remaining links to relatively recent ancestors. Others have retained parts of their culture, but with gaps that these objects may fill. In some cases it seems that Native artists living at that time may have deliberately sent objects away to distant museums as a way of preserving the information they contained.

These visits therefore combine historical and technological research with profound emotional engagement. These are not the curious or educational trips of the British public, but literally pilgrimages to sites of sacrifice, memory and even grief, with the hope of bringing home some lost connection.

My personal research project is to study these trips; to access the archives in museums to see how British institutions and the British public facilitated these engagements; to speak to participants, British and Native, and find out what lasting effects the exchange had for them and their communities; and to run a series of residencies and exchanges to study how communication and engagement might be better achieved so that the legacies of these events are longer lasting and more valuable.

Ultimately I hope to be able to take steps to in some ways reverse the exhibition “confections” of previous generations and influence how museums and the British public understand these objects in their collections in the context of their original communities and for the people for whom they mean the most. I will look at how these stories can be presented in ways that better acknowledge the diversity and emotional complexity of their stories, and how to better enable peoples in far flung parts of the world to engage with their own scattered heritage.

Thanks Ian, this is very interesting and the detail on those pieces is excellent. I expect the timing of the painting is significant; Wright painted it in c.1783-84, which was of course the end of the American Revolutionary War.

It was common for British army officers serving in North America to commission entire suits of brightly decorated “Native-style” regalia from Native American allies, complete with tomahawks, bows and arrows, garters, hats and moccasins. When the war ended the returning soldiers brought these items back to Britain with them and they formed much of the collections of Native American material in British stately homes which were broken up for sale in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This material was often available for study by painters.

I don’t know if the collection to which Wright had access has survived – it would make an interesting research project. A similar collection which is well-provenanced is that of Benjamin West, who in 1770 used a similar collection of material made during the Seven Year’s War to paint his famous canvas “The Death of General Wolfe” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Death_of_General_Wolfe )

West’s collection partially survived into the 1980s, and was purchased by the British Museum, where it has been the subject of a number of publications and exhibitions.

(http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx?people=103205ðname=1884 )

Many thanks

Jack

Hello Jack,

An interesting piece and an interesting research project. I was at the Museum of Derby recently for a brief talk on Joseph Wright’s “The Indian Widow” although the “widow” in question is a lot more classical than Native the objects hanging from the tree in the painting are so detailed I can only image that Wright must have been basing them on objects he had actually seen. I didn’t know if this was of any interest to you, but I thought I would pass it on.

Cheers

Ian Chambers