Professor Cecilia Morgan (University of Toronto)

A Cherokee-Scots soldier, interpreter, and journal-writer visited London in 1804. He arrived as an emissary for the Haudenosaunee Pine Tree Chief Captain Joseph Brant, hoping to settle Brant’s claims to land at the Grand River Territory in southern Upper Canada (present-day Ontario). From the 1830s to the 1860s, a group of Anishinaabe men – and one woman – travelled from Upper Canada to Britain and Europe. They too hoped to settle land claims but also to raise funds for the Methodist church’s missionary work among their people and advocate for temperance and international peace. Simultaneously, other Anishinaabe people appeared in Britain to perform in dance troupes for audiences in a number of British and European cities. Later in the nineteenth century, a Haudenosaunee writer, performer, and lecturer travelled to Britain and ended his days there, dying in a London hospital in 1914. His counterpart, a Mohawk-English poet visited London in 1896 and 1904, where she performed her poetry, wrote for the London press, and took tea on the House of Commons terrace. Throughout all these public displays and performances of Indigenous identity, culture, and history, these men and women also forged new families, entering into relationships that were often a direct result of their travels. In that respect, they were not alone. Cree-British children from the northwest fur trade and the new colony of Red River also voyaged across the ocean to be educated and meet members of their fathers’ Scottish or English families.

As other studies of Indigenous travel to Britain show, these men, women, and children were not alone, nor were their voyages merely historical curiosities without larger meaning and significance. Moreover, by the nineteenth century Indigenous people’s presence in metropolitan centres was not a new phenomenon. The conclusion of the War of 1812, though, had long-lasting consequences for Indigenous people in British America: they were no longer seen as valuable military allies with whom diplomatic alliances were necessary. Instead, in the eyes of both the imperial and settler governments they were dependent subjects whose geographic containment and eventual assimilation were crucial in order to free up land for increasingly large numbers of British immigrants. It is in this context, then, that these travellers’ voyages took place: travel was a form of resistance or, at the very least, a way of negotiating with changes that bought about growing restrictions on Indigenous peoples’ mobility.

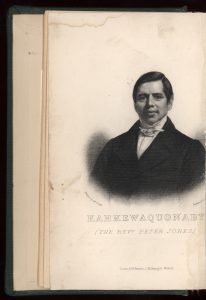

These travellers met these challenges with determination and creativity, demonstrating savvy, strategic ways of dealing with both imperial and settler governments and societies. They formed alliances with humanitarian networks, appealing to the better nature of audiences throughout Britain for support, and cultivated political ties with prominent individuals. They also participated (if at times uneasily, well aware of the stakes of being a highly visible colonial body in the metropole) in celebrity culture in Britain, and seized the opportunity to lecture British audiences: not just about their own territories and ancestral homelands but also about Britain itself, crafting ethnographic portraits of British society, an entity they did not hesitate to criticize. They could be found in a wide range of places and sites: speaking in front of audiences in London, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Dublin, appearing at court in front of Queen Victoria, touring the House of Commons, performing in theatres around Britain, and travelling in railcars, lake steamers, and carriages throughout the country. Furthermore, their words and, at times, representations of their bodies could be found in the pages of British newspapers: the growth of the press and of transportation networks throughout Britain meant that these travellers reached an even greater mass audience than their early modern predecessors. Portrait painters and, increasingly, photographers also recorded their presence in the metropole.

[Library and Archives Canada PA-2984984]

[The Grey Roots Archival Collection, Owen Sound, Ontario]

[Victoria University Library, Toronto]

[Victoria University Library, Toronto]

[Archives of Manitoba]

[Nairn Museum, Scotland]

Cecilia Morgan teaches history at the University of Toronto. Her most recent book is Travellers Through Empire: Indigenous Voyages from Early Canada (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017) – available here: Amazon and MQUP.