When we ran the ‘Inspiring Women’ of Tunbridge Wells project in 2013, we included some biographies on the website (which can be seen here). At the time there were several more women we would have liked to have included had there been enough time and enough information on them to hand.

One of these was Edith Abbott. Although not a leading player in Tunbridge Wells’ suffrage movement, Abbott made her mark locally through her support for and involvement in socialist movements and her leadership of the local Women’s Co-operative Guild (WCG). In the latter organisation she even had something of a national profile.

Edith Robinson was the eldest child of Henry Peach Robinson, a pioneer in the photographic business, and his wife, Selina, who was also a photographer. She was born in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, but by 1871 the family had moved to a different spa town, Tunbridge Wells. Artistic like her parents, Edith grew up to be an art teacher: at some stage she taught art at the Tunbridge Wells Girls High School and after her marriage taught drawing at the town’s technical institute.

In 1892 she married George Abbott, another leading citizen of her adopted town. George was quite a bit older than Edith. He was already in his late forties when they wed and had been married before: in the 1891 census he is recorded as a widower. George came from humble origins in Nottinghamshire, but had qualified as a medical doctor and practiced as an ophthalmic surgeon. Among the causes he passionately promoted were the technical institute and the town’s museum (he was very interested in geology). In its report of the couple’s wedding, the Kent and Sussex Courier (23 April 1892) commented that ‘the bridegroom is known in the town for his indefatigable labours in connection with the Eye and Ear hospital’. In 1890 he instituted technical classes in the basement of his dispensary on the Pantiles. George was also active in local politics and was elected to the Tunbridge Wells council in 1898 (Courier, 16 Jan. 1925). George and Edith had no children together, but the 1911 census records an adopted son of Italian birth.

As a councillor, George Abbott was known as a ‘progressive’, which means that he was broadly left-liberal in politics. Julian Wilson’s recent research on Revolutionary Tunbridge Wells reveals that Mr Abbott co-operated with socialist forces on the Council, supporting, for example, a campaign in favour of municipal housing (Wilson, 147-8). George’s will was said to contain an astonishing diatribe against ‘stingy’ and ‘pennywise, pound foolish’ councillors and town clerks, on account of a generous donation that he wished to make for a museum having been allegedly rejected (Courier, 16 Jan. 1925).

Edith’s politics were not dissimilar. Although originally a member of Tunbridge Wells’ Women’s Liberal Association, by the First World War she was more closely identified with the labour movement. She was certainly a part of the town’s women’s movement, being an active member of the local branch of the National Union of Women Workers, established by Amelia Scott in 1895. Although she doesn’t seem to have held office in the local suffrage society, Edith Abbott was undoubtedly not only a suffrage supporter but also a believer in the necessity for women to become more involved in public life. On many occasions she spoke out in favour of the election of women as poor law guardians, councillors and to hospital boards etc. and repeatedly urged the (mainly working-class) WCG members to stand (for example in Women’s Penny Paper, 25 Mar. 1897). She followed her own advice when she became a member of Tunbridge Wells’ Education Committee, from which she retired in 1921 after ‘long service’ (Courier, 30 September 1921). After the First World War she was an enthusiastic supporter of Scott’s campaign for a maternity home and personally guaranteed the overdraft required to secure the home’s first premises in Upper Grosvenor Road (ibid. 26 Sept. 1924).

Edith Abbott also became very interested in the co-operative movement, and served as secretary of the local co-operative society and was president of the Tunbridge Wells WCG from 1892. This must have brought her closer to the town’s socialist movement. In the First World War she publicly supported local conscientious objectors (as did the Liberal Quaker, Sarah Candler) and she presided over many meetings with Labour Party speakers. In 1918 she became a member of the Tunbridge Wells provisional committee of the Labour Party (Advertiser, 15 Nov. 1918). She also spoke at many national meetings of the WCG, giving a talk in 1914 with the – perhaps rather dull but worthy – title, ‘On Reading Balance Sheets’.

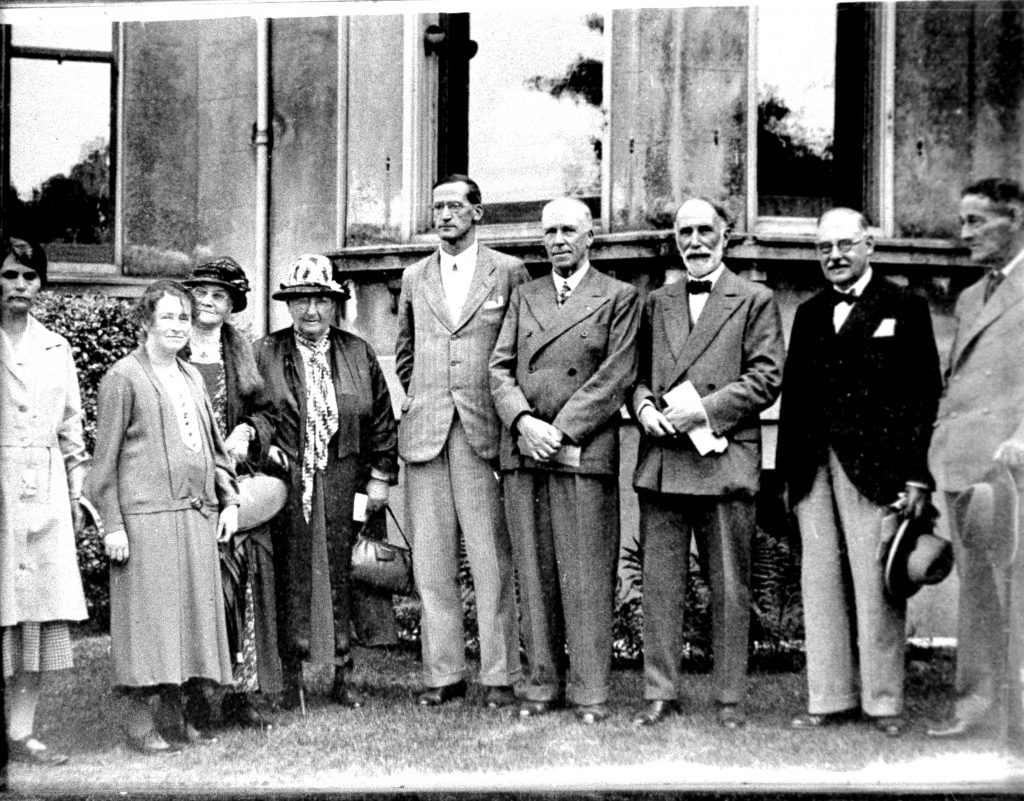

After George’s death, Edith continued to support her late husband’s work for museums and the South-East Union of Scientific Societies. When Tunbridge Wells Museum opened at new premises at 12 Mount Ephraim in 1934, she was pictured at the opening ceremony (above, third from left), standing next to Amelia Scott, another strong supporter of municipal facilities such as libraries and museums. Edith died in 1952 at the age of 92: coincidentally she was born and died in the same years as her comrade in the Tunbridge Wells women’s movement, Amelia Scott.

Anne Logan

Thanks to Ian Beavis, Julian Wilson and Alison Sandford MacKenzie.

Sources:

Census, birth, death and baptism records via Find My Past

Kent and Sussex Courier

Tunbridge Wells Advertiser

Women’s Penny Paper

J. Wilson, (2018) Revolutionary Tunbridge Wells (published by the Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society).

https://belgiansrtw.wordpress.com

Photo courtesy of The Amelia, Tunbridge Wells.