Starting up again after Easter, I was excited to see that the Bodleian’s Weston Library was admitting outside researchers for the first time since before Christmas, and emailed right away to check availability. The lovely staff booked slots for me and I ordered up five manuscripts. There were still hurdles to get over, of course, but they were all of my own making: find reader card (temporarily misplaced after months of disuse and a house move), secure pound coin for the lockers (strangely difficult after a year of avoiding physical money). Having done both, and feeling very fortunate to still be living so close by, I took a stroll in the morning sunshine down to the Weston on Thursday. It was great to be out of the house, frankly, but also to be in the library, and especially to see the familiar faces of the security staff and the librarians.

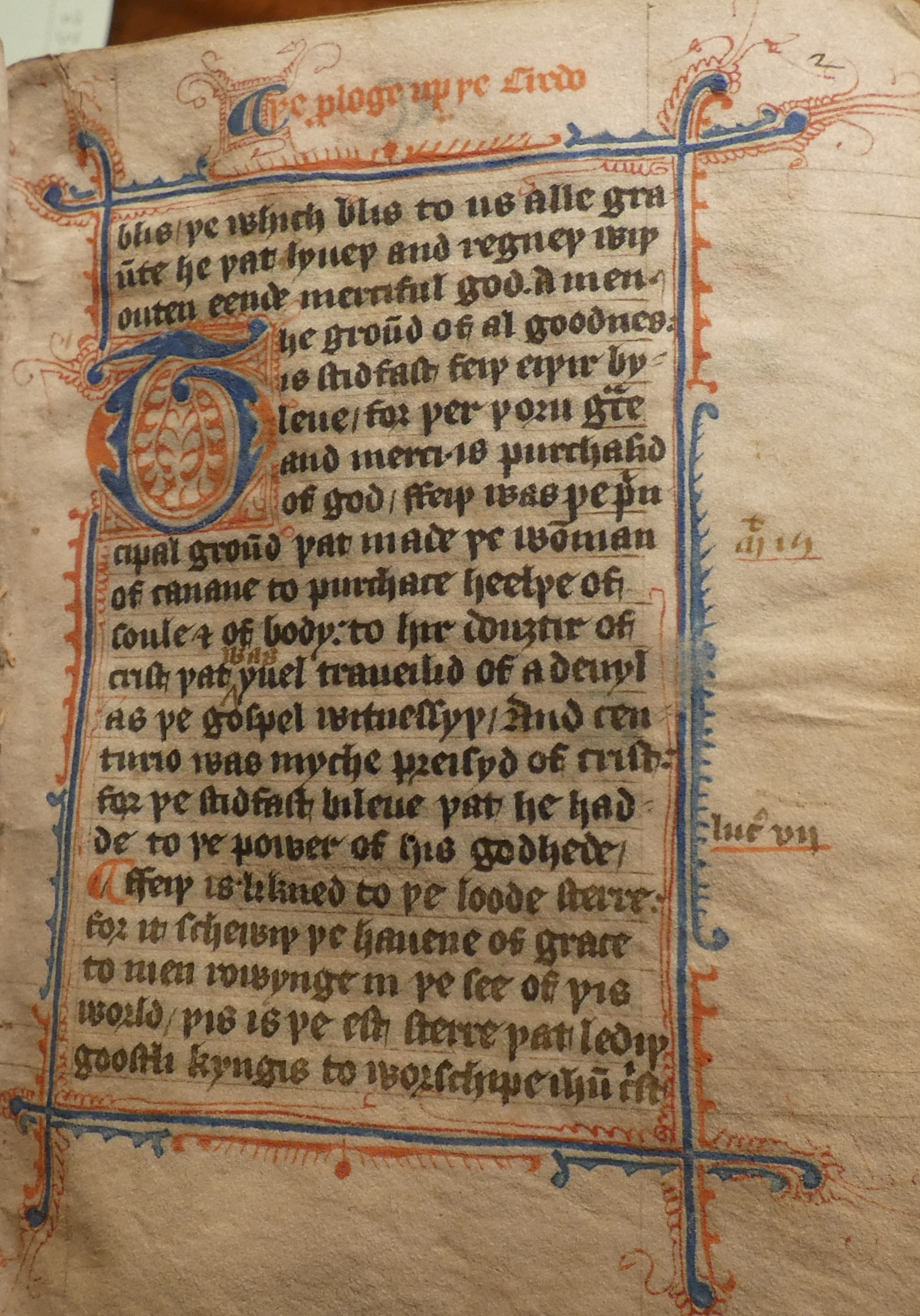

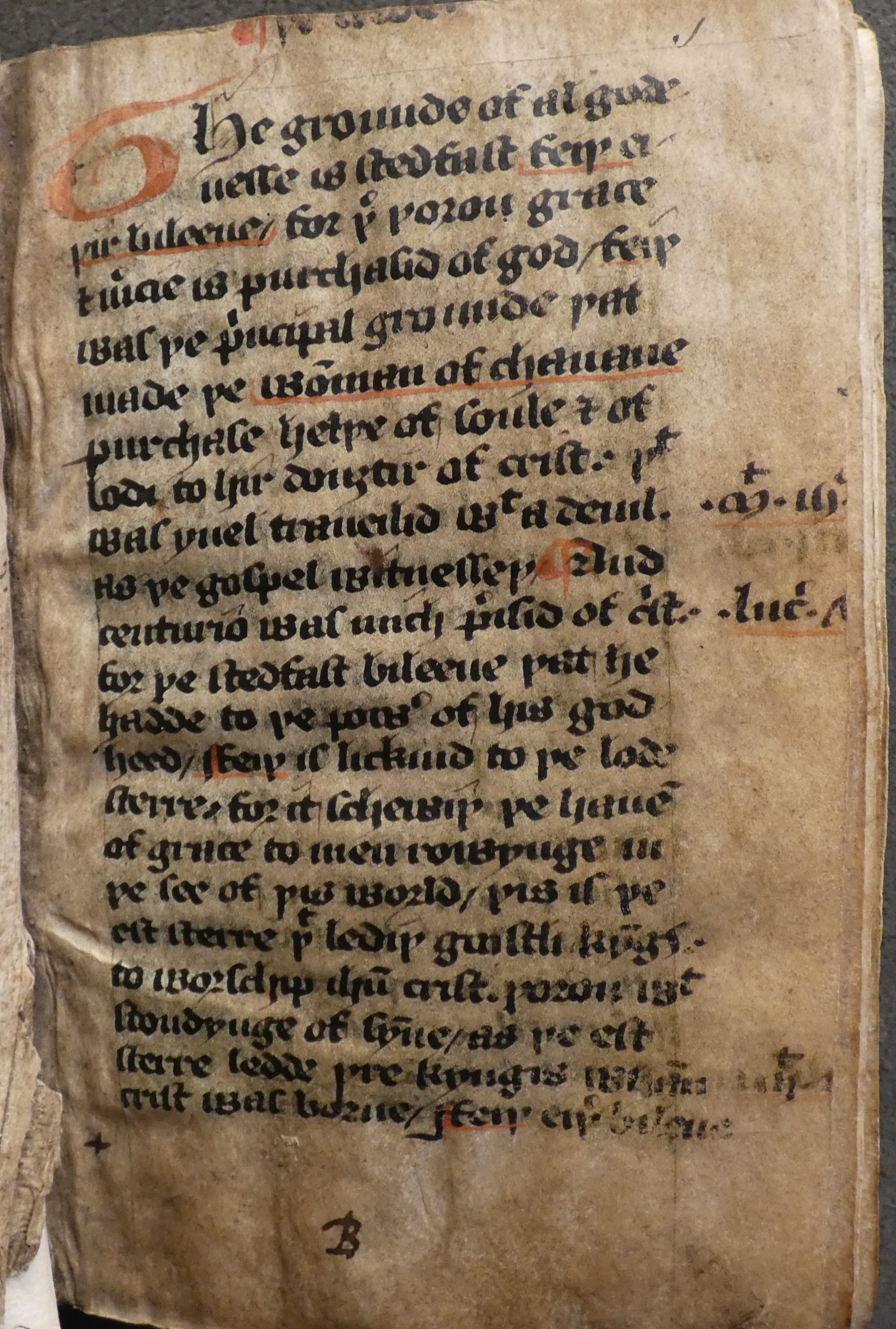

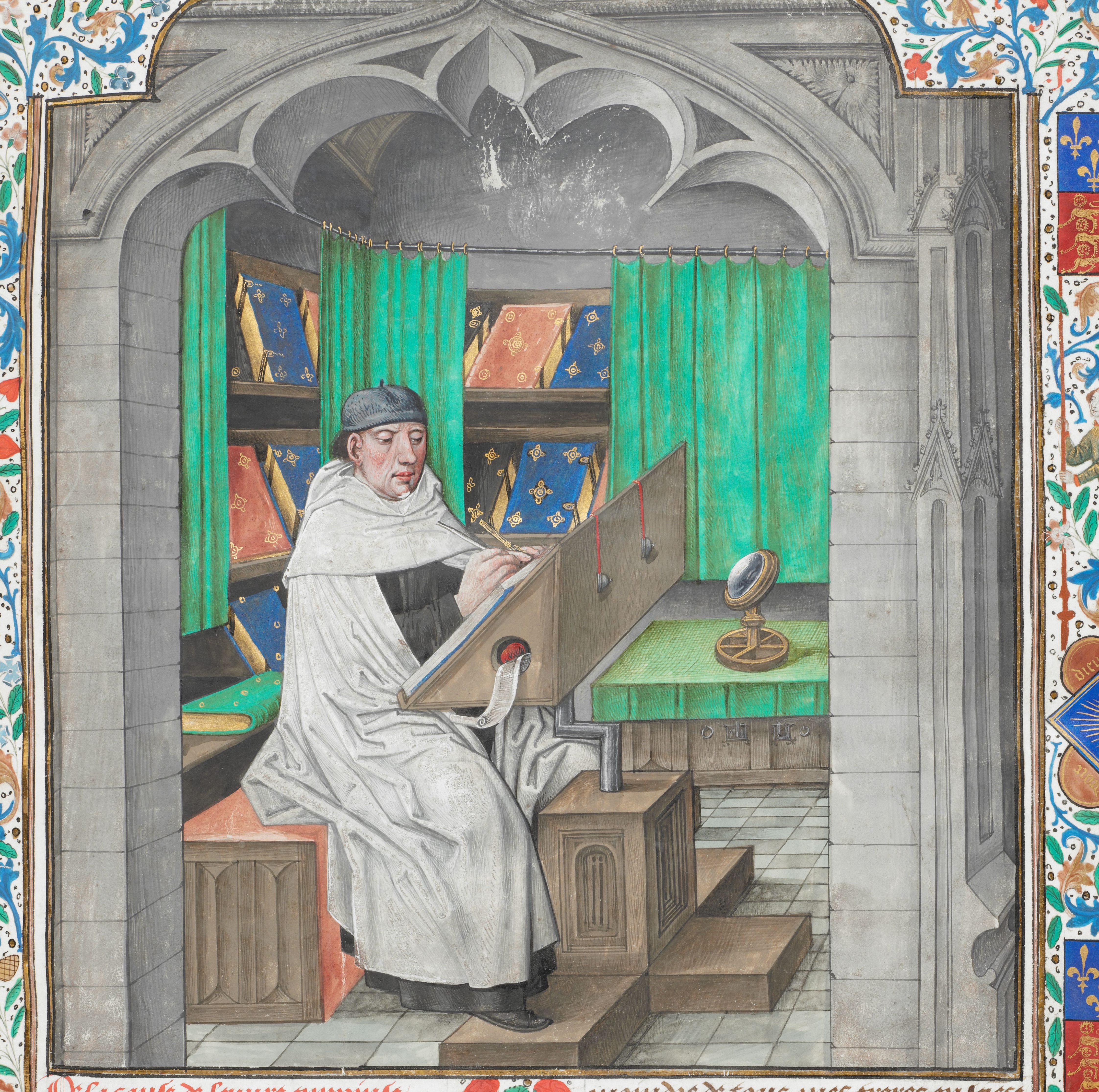

Examining the manuscripts themselves is brilliant, of course. Over the last few months I’ve been working a lot from monochrome microfilm images, which has been much less than ideal. Even the excellent resources I talked about in my last blog post, which include a lot of digitised manuscripts, can’t totally capture the material reality of these volumes, and given how central this is to the project, I was so glad to get going again. I started with five manuscripts which all contain a similar group of texts, albeit with rather different production values. Two of the group are pictured below. Many of the material differences between them would have been obvious in images, of course, even in monochrome, but it would have been difficult to gauge parchment quality, see all the corrections clearly, or get a concrete sense of their scale, among other things. Beyond this, there’s something about turning the leaves of a manuscript that forces you to engage with its materiality in a way that images just can’t.

Of course, it’s important to remember when handling these objects that they are unlikely to have survived the centuries unaltered or unscathed: originally unrelated booklets may have been bound together later; pages have often been cut down, resulting in the loss or damage of some marginal annotations and finding aids; folios may have been damaged or lost, particularly at the starts and ends of volumes. And even if the manuscript has survived more-or-less as it was when it was produced, we should remain aware that we are examining it several hundred years after the fact, under electric light in a modern library, bringing to it questions, attitudes and experiences very different to those of its original audience. Still, there is so much that can be gained from examining a manuscript in person, and I’ll be excited to share more on this in upcoming blog posts. For now, I’ll end by saying a huge thank you to all the library staff who have been helping to keep research going, in person and remotely, over this past year, and who will hopefully be able to welcome lots more researchers through their doors in the next few months.

– Hannah