There will always be uncertainty about when is the right time to introduce or remove COVID-19 restrictions. Clear guidance and communication of what the removal of restrictions means (full responsibility/ accountability is handed back to each individual) and does not mean (the end of the pandemic) would be crucial to enable everyone to make informed decisions. By Martin Michaelis and Mark Wass.

Boris Johnson has announced plans to remove all formal COVID-19 restriction in February, including the obligation to self-isolate when infected. Evidence in favour of such a move includes that the number of hospitalisations due to COVID-19 is decreasing. COVID-19 numbers have fallen but remain high at more than 50,000 reported cased/ day, which is an underestimation. The actual number of COVID-19 infections is estimated to be twice as high as the reported positive tests.

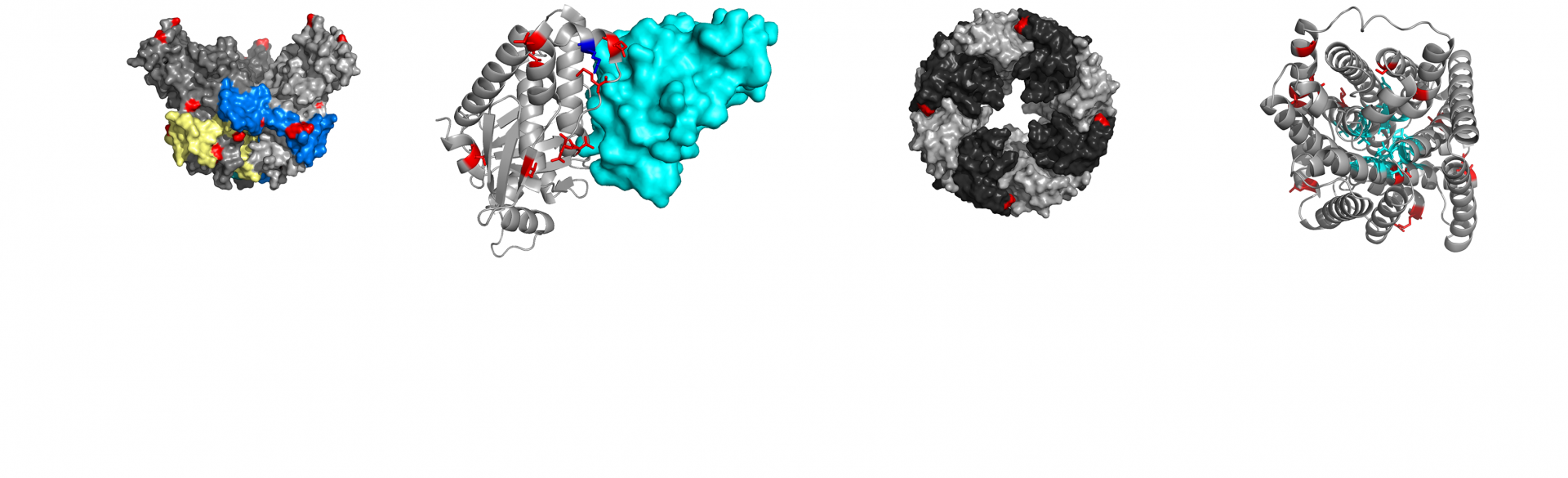

However, the proportion of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, who develop severe disease is much smaller than at the beginning of the pandemic. This is partly due to increasing immunity due to vaccinations and/ or previous infections across the population and to an inherently reduced capacity of the Omicron variant to cause severe disease.

Therefore, it is possible to argue that currently COVID-19 does not pose a major health emergency, which is a compelling reason to remove restrictions to the freedoms of individual residents. If there is no acute and urgent threat to large parts of the population, people should be allowed to make their own informed decision.

Arguments against an early removal of restrictions include the uncertainty. It is not clear what impact this easing will have. Removing restrictions will result in more infections and put the health system under more pressure, although we cannot predict to which extent. Waning immune protection from vaccines and previous infections may not play out in our favour.

Moreover, the removal of restrictions at a time when 1 in 19 individuals in England is infected with COVID-19 puts people at risk, who do not have a fully functional immune system and cannot protect themselves by vaccination. Such individuals will find it difficult to protect themselves.

Much will depend on official guidance and the subsequent behaviour of the public. Will the majority consider the removal of restrictions as a mandate to take on responsibility and accountability themselves? Or will people see this as a sign that the pandemic is over and return to their pre-pandemic behaviour?

It is also not clear whether the current testing programmes will continue or not. If they are stopped, guidance to self-isolate when infected will be largely meaningless, because people will at least initially not know whether they have COVID-19 or another respiratory illness.

Taken together, the removal of all restrictions despite high infection rates is a gamble that can either be considered as bold or as reckless. Erring on the safe side would have seemed to be a more prudent approach in a pandemic. Moreover, immunocompromised people will be put at an increased risk or sent into strict self-isolation. The outcome will at least in part depend on the guidance that will replace formal restrictions. The pandemic is unlikely to be over, which means that after a wave is also before the next one and that we still have to find a way to live sustainably with COVID-19 without a need to repeatedly reintroduce restrictions.