Peter Taylor-Gooby, University of Kent and Tomas Petricek, University of Kent

Food banks in the UK reported that demand had tripled in March this year as the coronavirus lockdown threw millions out of work. Many food banks faced an urgent need for money to buy extra food and launched appeals through crowdfunding websites.

The public response was impressive, with a massive surge in support. Nearly a million people volunteered to help the NHS and local support centres.

Later, public backing for footballer Mark Rashford’s appeal also forced the government to reverse its decision not to continue funding free meals for the nation’s poorest children over the summer holidays.

This surge in generosity has led to hope that the pandemic signals a transition to a kinder and more humane society after the pandemic. To find out whether that might be the case, we developed a piece of data scraping software to chart the generosity of the public in response to appeals by food banks. We looked at how much was being donated during the pandemic to see if the goodwill was sustained.

Surge in support

Food banks are held in high regard. Nearly 90% of those questioned in a recent Trussell Trust survey approve of them and 35% report making food donations. In normal times they collect most of the food they give out from the public, but need to pay organisers, run vehicles and provide warehouses.

Much of this funding comes through donations from supporters and grants from trusts or local government. Appeals to the general public through crowdfunding sites usually make up a relatively small part of their income but now they need money to buy extra food and traditional sources of support are under pressure, hence the crowdfunding appeals.

Our research traces the success of the various pandemic appeals on the main crowdfunding sites (GoFundMe, Just Giving and Virgin Giving).

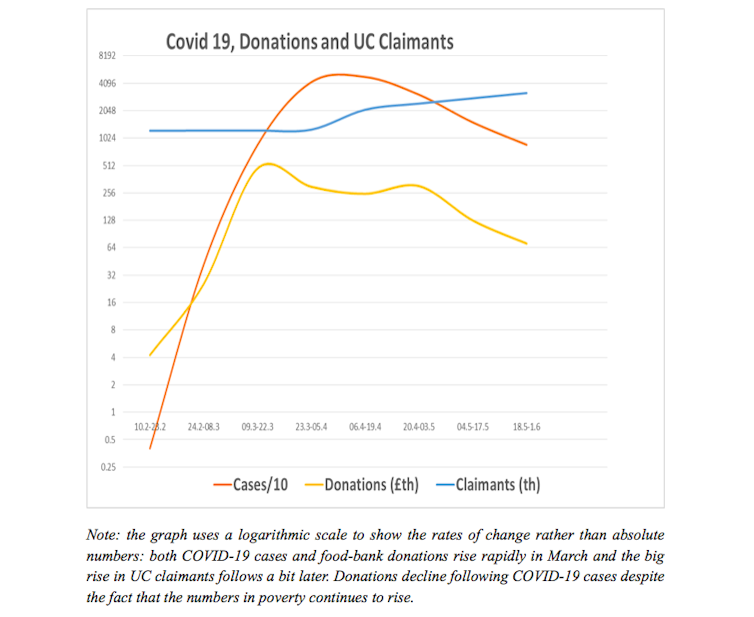

We found that the amount raised took off in step with the numbers of coronavirus cases and also followed the growth in the numbers claiming out-of-work benefits.

The chart shows great and unexpected public generosity. People wanted to help those in need of food aid just as they felt the impulse to volunteer. The growth in donations provides evidence of commitment to others.

As the health crisis peaked, so did donations. The uncomfortable news, however, is that support tailed off just as the number of COVID-19 cases declined from April onwards, even though the numbers in need of support continued to rise. This indicates that public generosity is a response to the impact of the pandemic and the feeling that “we’re all in this together” rather than to the needs of those who lost their jobs.

Author provided

The decline in infections has not been matched by a decline in need. In fact, as time wore on – and as donations declined – the number of people needing help from food banks has actually increased.

And now that people face losing their jobs as furlough schemes come to an end and the recession bites home – with a possible further impact from Brexit – food banks continue to report a high level of demand.

Regional mismatch

The problem is exacerbated by evidence that people in richer areas of the country give most – London in particular, but also eastern England and Yorkshire. These are not the areas with the highest rise in job losses and benefit claiming, where the demand on food banks is greatest (the north-west, the north-east and the West Midlands).

We are moving from a situation where furloughing has been the main support system for those unable to work due to the pandemic, to one where unemployment and benefit-level income will be the norm. This will drive more families to food banks.

The pandemic is widely seen as a common threat – “we’re all in this together” as the prime minister put it. Mutual support, good neighbourliness and a willingness to help others characterised the initial response, leading some to raise the question of whether these acts of kindness presage a shift towards a more cohesive society.

The evidence from food banks indicates that food poverty will continue to afflict vulnerable families, but that the public generosity during the COVID-19 crisis is exceptional and will not become the “new normal”.![]()

Peter Taylor-Gooby, Professor of Social Policy, University of Kent and Tomas Petricek, Lecturer, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.