As the date of the UK’s EU referendum fast approaches, the implications for the EU as a whole, if the UK votes to leave, has attracted limited attention in the campaign. Even further, apart from a flurry of interest at the time of the renegotiation, the impact of the Prime Minister David Cameron’s renegotiation deal on the EU itself if the UK stays has scarcely been mentioned. Yet what the Prime Minister achieved has the potential to transform the EU for, at the heart of the renegotiation, is a new vision of a more flexible, differentiated EU. After June 23, whether Britain leaves or remains in the EU, its future structure will be up for debate.

While much of the settlement agreed in February consolidates and extends the UK’s existing special status within the EU, the deal also has implications for the rest of the EU. For the first time ever in a legally binding decision, the EU Heads of Government have recognised that references to ‘ever closer union among the peoples of Europe’ are ‘compatible with different paths of integration and do not compel all Member States to aim for a common destination’. In other words, the Decision explicitly acknowledges that not all EU member states share the same vision of European integration, nor are they all heading, at different speeds, in the same direction.

This marks a fundamental shift away from the unitary principle that has underpinned the process of European integration until now, a fundamental tenet seen to be enshrined in the very goal of ‘ever closer union’ and a single EU legal framework.

Back in February, the contrast in response to the renegotiation deal in the UK and elsewhere in the EU could not have been more stark. While politicians and media commentators in the UK variously described the deal as ‘thin gruel’, ‘flimsy’, and ‘the great delusion’, elsewhere in the EU it was seen as rather more significant for the future of European integration, heralding a more pliable EU and even bringing treaty change in ‘through the back door’.

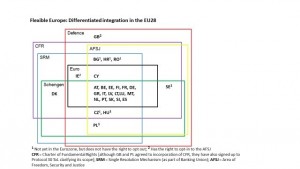

At the heart of the Prime Minister’s renegotiation was his vision of a flexible EU. And what’s so new about this, one might ask? It is clearly the case that EU member states do not partake equally in all EU activities. Differentiated integration, used interchangeably with ideas of flexibility, has existed in the EU since the UK and Danish governments opted out of Economic and Monetary Union in the Treaty of Maastricht. The subsequent treaties of Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon added new opt-outs and opt-ins across a range of policies, as well as the possibility for further flexibility with the mechanism of enhanced cooperation, where a smaller group of member states could move forward and cooperate more closely in specific areas, subject to certain conditions.

Since then it is fair to say that variations in the level and intensity of participation of member states in various EU policies have become even more evident. Solutions to the Euro debt crisis added to the EU’s differentiation and the response to the refugee crisis has further amplified disparities between member states. Described by Guy Verhofstadt as ‘a hotch potch of opt-ins, opt-outs and rebates and a laundry list of other exceptions’, differentiation between member states’ commitments to EU policies is thus an ever-increasing reality in the EU.

Yet in its early days, the use of such differentiation was somewhat contentious. In the late 1990s a vigorous debate took place about various models of differentiation such as ‘multi-speed Europe’, a Europe of ‘variable geometry’ (with a hard core at the centre) and à la carte Europe. Symbolically, for many the phenomenon of differentiation was seen as the exception and temporary, a tool to help member states overcome gridlock and move at different speeds in the same direction. Equated with fragmentation, differentiation was something to be avoided if at all possible (and not to be overtly acknowledged).

This is where Cameron’s deal comes back in. As well as exempting the UK from any further political integration, excluding the UK from ‘ever closer union’ and providing further safeguards for non-Eurozone members, Section C on Sovereignty of the UK’s Settlement, with its declaration of different paths of integration, affects all EU member states. In so doing it brings ideas of differentiation and flexibility back into the political debate. More significantly, it means that no matter what the outcome, the UK’s referendum result will have implications for the future of the EU.

If the UK electorate votes to remain in the EU, it is quite possible that other EU member states, looking at what the UK has achieved through its negotiation in gaining a ‘special status’, may also wish to claw back powers from Brussels in response to nationalist pressures. Indeed, if ever and whenever a new EU treaty is negotiated in the future, negotiations could very well focus on ‘less Europe’ for some member states rather than solely on ‘more Europe’ as was the case in the past.

Some will argue that this will destabilise the EU, giving rise to centrifugal pressures as flexibility becomes both a brake and an enabler of European integration. It would certainly increase the complexity of the EU. On the other hand, greater flexibility might be seen as a good thing, as reflected in Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond and Italian Foreign Minister Paolo Gentiloni’s call last December for ‘a flexible reformed EU in which different paths of integration can coexist successfully to build a Europe fit for the future’. For them, ‘a successful EU will be one which can combine these different visions of Europe and embrace that diversity’.

And what if the UK votes to leave? As the most differentiated EU member state, the departure of the UK would certainly decrease policy complexity and divergence in the EU. It would also mean that the EU would be more likely to remain on the ‘multiple speed’ track of integration, particularly with the possibility of further integration of the Eurozone down the line.

Whatever the outcome on June 23, the question ‘quo vadis Europa?’ will be back on the agenda.

Dr Jane O’Mahony, Senior Lecturer in European Politics, School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent

This blog also appeared on the ESRC’s UK in a Changing Europe website available at: http://ukandeu.ac.uk/dont-forget-the-deal-how-camerons-uk-eu-settlement-could-herald-a-more-flexible-eu/