What effect might Britain’s party leaders have on the referendum on the country’s continued European Union membership? In the social sciences it is well known that leaders can have decisive effects on the outcome of elections and referendums. Amid complex debates, it has been shown that citizens often rely on their leaders to provide “informational shortcuts” or “cues” that help them decide how to vote. The same is true for referendums, where leaders can play important roles by helping voters make up their minds about how to vote. All of this raises an intriguing question. What effects will the Conservative Party leader David Cameron, Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn and Ukip leader Nigel Farage have on the public vote? Are they likely to galvanise public support for remaining in the EU, or might their campaigning increase the prospect of Britain leaving the EU? And how do their effects vary across electorates, age groups and social classes?

To answer this question we carried out an online survey experiment with YouGov, supported by theEconomic and Social Research Council. Our experimental design allows us to explore the effects of leaders in a far more robust way than a standard poll or survey. Experiments can establish cause and effect while holding other variables constant – in this case testing the effects of leaders on the referendum vote. We randomly applied one of five “treatments” to a representative sample of over 5,000 adults. The fieldwork dates were October 1-12 2015. The control treatment involved asking the following question:

“There is expected to be a referendum in the next few years on Britain’s membership of the European Union. If this is the question, how will you vote? Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?” Answer choice: Remain, Leave, Don’t Know, Would not Vote.

The other four treatments involved a “party leader prime”, the first of which was: “If David Cameron recommends people vote to remain a member of the European Union and this is the question, how will you vote?” The other primes involved Jeremy Corbyn recommending a Remain vote, Corbyn recommending a Leave vote and Nigel Farage recommending Leave. Unlike Corbyn, who has shown some ambivalence on this question, Cameron has clearly decided to campaign to keep Britain in the EU. So, what did we find?

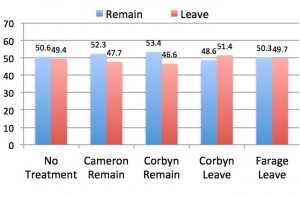

Our experiment suggests that the remain-or-leave vote is very close. When asked how they plan to votewithout any leader recommendation, 50.6% would vote to Remain in the EU while 49.4% would vote to Leave (excluding Don’t Knows). This is extremely close and, after recent polls, provides more evidence that only a few points separate the two sides. Who are these people? We find that a majority of Conservative Party voters want to Leave the EU, while large majorities of Labour, Liberal Democrat and Scottish National Party voters want to Remain. Younger Britons are notably more supportive of Remaining than older voters, as are people in higher (AB) social grades, who are more likely than more financially insecure lower (DE) social grades to want to stay in the European Union.

What is different about our experiment is that by using primes we can test for the effects of leaders, at the aggregate level, and among different electorates, ages and classes.

Prime minister Cameron is likely to have a significant effect on the vote. If Cameron recommends that Britain remain in the EU, public support for doing so rises to 52.3%, about 2 points higher, while support for Leave drops below 48%. Cameron’s recommendation increases support for Remain amongst Conservative voters, by around two points. However, Cameron actually has stronger effects on Labour and Liberal Democrat voters, both of whom seem to be more responsive to his recommendation to Remain. While clear majorities of Labour and Liberal Democrat voters are already planning to vote to stay in the EU (75% and 80% respectively), these figures increase by 6 and 10 points following a nudge from Cameron. In contrast, in our data Cameron has no effect on Ukip voters and actually makes SNP voters less likely to vote to remain. This suggests that, in broad terms, Cameron is an asset for Remainers, as he was for the Conservatives at the recent general election.

There are, however, some variations. Cameron has little effect on younger or older voters if he recommends a Remain vote. But among 40-59 year olds, Cameron increases their support for Remain by a highly significant 10 points – one of the biggest effects we find. So, while Cameron would be well advised to stay away from Scotland, he might want to focus on wavering Labour and Liberal Democrat voters and the middle-aged.

What about Jeremy Corbyn? The Labour leader also has significant effects. Should Corbyn campaign to Remain in the EU, which he has suggested that he will, then support for Remain increases by a statistically significant 2.8 points. When presented with a pro-EU recommendation from Corbyn support for Remain increases from nearly 51% in the non-treatment group to over 53%. Among Labour voters he would help to drive their support for Remain by a significant 7 points. In terms of age and class, he increases support for Remain amongst 40-59 year olds by a significant 10 points. Our findings also suggest that Corbyn would mobilise support for Remain among the C1 and DE social groups, amongst whom he is a particular asset.

But what happens if Corbyn has a change of heart? Were he instead to campaign for Britain to Leave, perhaps pushed by his known concerns over a lack of protection of workers’ rights, this would have a profound effect on the vote. Public support for Remain would fall by 2%. The magnitude of this effect is small, but statistically significant. What is important about this finding is that if Corbyn recommended a Leave vote, overall support for Remain would fall to less than half, 48.6%,while support for Leave would rise to 51.4%. Most of this change would come from voters in lower social groups who currently ‘don’t know’ which way they would vote, but would be more likely to support Leave if Corbyn supported this view. In other words, if Corbyn did switch he would decisively alter the referendum outcome.

What about Farage, the Ukip leader who some claim will alienate wavering voters and scupper any chance of a victory for the Outers? Overall, we do not find much evidence for the claim that Farage will make large numbers of voters more likely to vote to keep Britain in the EU. Compared to voters who arenot exposed to a Farage cue, those who are given this treatment are no more likely to vote to Leave. Broadly speaking then, it appears that voters have already priced in the so-called ‘Farage Effect’.

While the Ukip leader does not affect the overall outcome, however, there is some evidence that he has an effect among specific groups. When Conservative voters are told that Farage recommends a Leave vote, their support for Remain falls by 6 points. It is a different story among Liberal Democrats, however, whose support for Remain increases by 8 points, providing some evidence of a ‘backlash effect’.

Overall, therefore, our experiment provides a first look at how the positions of three of Britain’s major political parties might influence the outcome of the referendum and, in the case of Jeremy Corbyn, decisively so. This is part of a longer strand of work that we will continue to share as Britain’s referendum debate progresses.

This is a copy of a blog that featured on http://whatukthinks.org/eu/ available at http://whatukthinks.org/eu/cameron-corbyn-and-farage-how-might-they-affect-the-eu-referendum-vote/.

This blog was co-authored by Matthew Goodwin, Simon Hix and Mark Pickup

Simon Hix is Harold Laski Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics and Senior Fellow with the ESRC ‘UK in a Changing Europe’ programme. Mark Pickup is Associate Professor in Political Science at Simon Fraser University.

The authors would like to thank Professor Anand Menon and ‘The UK in a Changing Europe’ for providing financial support for the study, and Anthony Wells and YouGov.

Matthew Goodwin is Professor of Politics at the School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent and Senior Fellow with the ESRC ‘UK in a Changing Europe’ programme.