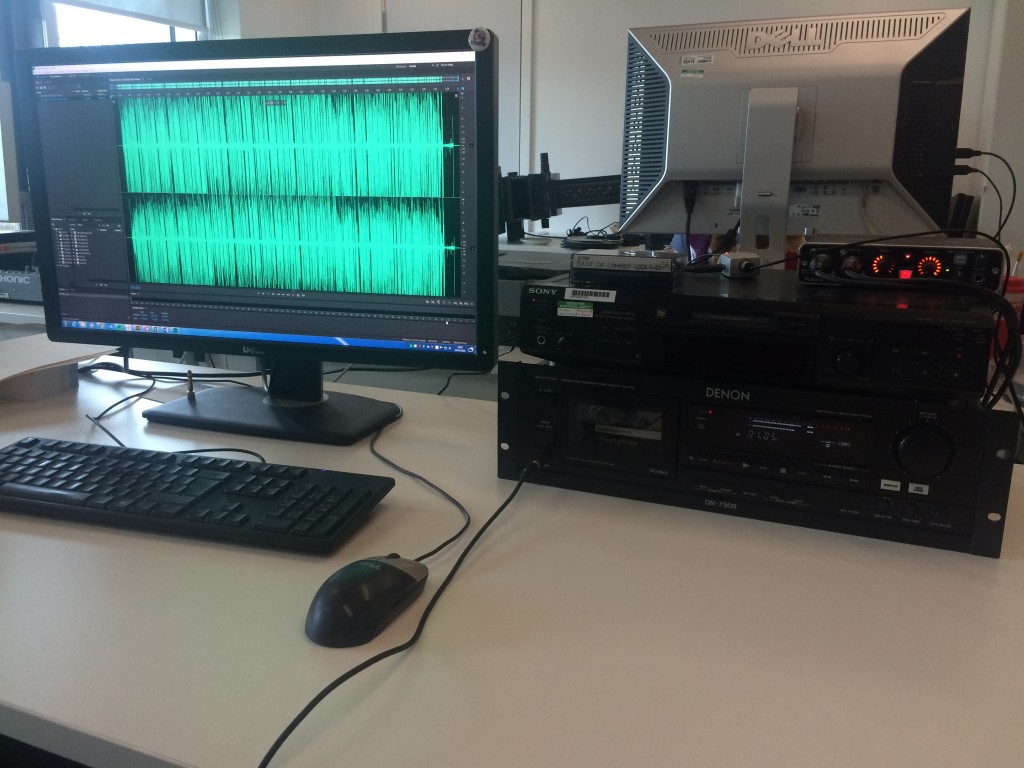

Following on from my last post I thought I would provide some information on the equipment that we are using for the digitisation (or capture) of audio held on various audio formats. As stated before, we have had to compromise in various areas:

- We have purchased second-hand equipment as that way it is possible to use semi-professional equipment. There were no newer models, within our budget, for semi-professional use, only those created for domestic purposes (which didn’t have XLR connectors or noise reduction settings for example).

- We have borrowed or been given equipment from other departments around the University, no longer used by that department due to its obsolescence, but perfect for the requirements of our project.

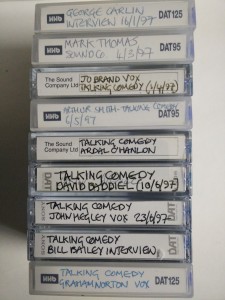

- And we have had to outsource some digitisation (so far of DAT and U-Matic).

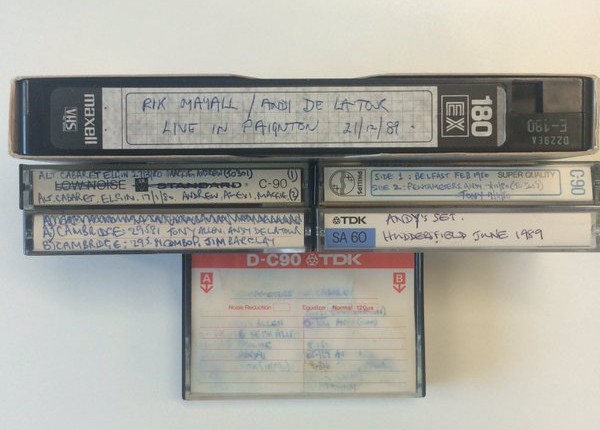

Audio cassettes

- Cassette Deck: We are using the Denon DN 790-R. After lots of research I chose this as an it was affordable option for a semi-professional cassette deck, and it was a deck that I could actually find for sale at the time I was looking (we paid about £300 for one off of Ebay). I was looking for a deck which had XLR connectors and a variety of dolby noise reduction settings. Best practice (for example see Sound Directions, page 20 or Digitising Speech Recordings for Archival Purposes, page 8) would dictate that you find a cassette deck with XLR connectors as these are important for achieving a balanced signal. Noise reduction is also important, and if the original cassette was recorded with a noise reduction applied, then this should also be applied during digitisation. If the cassettes were recorded in the 1980s/1990s Dolby B (in particular) might have been applied. From experience within the British Stand-Up Comedy Archive, cassettes which were recorded professionally seem to have been recorded with a noise reduction applied (and sometimes this is even noted on the cassette which is really helpful!) but those more ‘home made’ recordings often don’t have any noise reduction; in these cases it is best to transfer without any noise reduction.

- Audio capture card: We’re using a Roland UA-55 Quad-Capture audio capture card, again as this was quite an affordable option (c.£150). This is, in effect, an external sound card; the alternative would be to use an internal sound card with XLR connectors (which you’d have to install). We did actually purchase a good video capture card to use for both our audio and video digitisation work, but this had compatibility issues with our PC and so I sought an affordable capture card so we could start digitizing audio (we are using this video card in a mac tower for our VHS work though). An easy alternative (but which would not result in the best quality capture, especially if you are digitising for preservation) would be to use the PC’s existing internal sound card if you were digitising using stereo phono connectors (not recommened for preservation work).

- Cables: two XLR connectors to connect the deck to the capture card; a usb cable connects the capture card to the PC (this would probably come with your audio capture card).

- Software: we’re using Adobe Audition as it is part of the Adobe Creative Cloud package. As we are using some other Adobe CC programmes for image digitisation and embedding metadata (such as Bridge and Photoshop) this seemed the best option for us. A free and good option is Audacity (http://audacityteam.org/). When capturing audio it is best practice to capture to at least 24 bit 48kHz (fine for spoken word, although for music it is recommended to captured 24 bit 96kHz). More information on this can be found on the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives website and ‘guidelines for the production and preservation of digital audio objects’

MiniDisc

MiniDisc capture has been a bit more of a compromise, in terms of our equipment:

- MiniDisc Deck: We are using the Sony MiniDisc MD5-JE530 as this is a deck that was already available to us from within Campus Support here at the University of Kent (so free. We have also since been donated another MiniDisc deck by the School of Engineering and Digital Arts – thanks EDA!)

- Audio capture card: Roland UA-55 Quad-Capture USB Audio/midi interface (price as above). The MD5-JE530 has an optical digital connection, whereas the UA-55 has a coaxial digital connection only. We didn’t want to purchase an additional audio capture card just for MiniDiscs so we purchased…

- …the Pro-Signal PSG08095 Optical to Coaxial Adaptor (under £10) and a…

- ….Digital Audio Coaxial Cable (1m) (about £2)

- Software: Adobe Audition (as above). MiniDiscs used the ATRAC (Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding) compression which sampled at 16 bit 44.1kHz and so when transferring MiniDiscs we capture at this rate (capturing at a higher bit rate and sampling frequency will only increase the file size but not the quality).

I aim to provide more updates soon, looking at how we are transferring digital files held on other physical media (such as audio CD and DVD), and in time we will also report on our VHS digitisation.

Reading list:

- Jisc Digital Media, ‘Equipping an Audio Digitisation System’, http://www.jiscdigitalmedia.ac.uk/guide/equipping-an-audio-digitisation-system/show-hidden

- Dietrich Schüller, Audio and video carriers: Recording principles, storage and handling, maintenance of equipment, format and equipment obsolescence, http://www.tape-online.net/docs/audio_and_video_carriers.pdf

- Mike Casey and Bruce Gordon, Sound Directions: Best Practices for Audio Preservation, http://www.dlib.indiana.edu/projects/sounddirections/papersPresent/sd_bp_07.pdf

- International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives, IASA-TC 03 The Safeguarding of the Audio Heritage: Ethics, Principles and Preservation Strategy, version 3 December 2005, http://www.iasa-web.org/sites/default/files/downloads/publications/TC03_English.pdf

- Bartek Plichta and Mark Kornbluh, Digitizing Speech Recordings for Archival Purposes, http://www.historicalvoices.org/papers/audio_digitization.pdf